The Korean War: Phase 3

3 November 1950–24 January 1951

(CCF Intervention)

Courtesy of the Center of Military History

Republished by the USASOC History Office, August 2020

Chronology

| 3-6 Nov | Communist Chinese Forces (CCF) offensive continues in Eighth Army and X Corps zones. |

| 11 Nov | X Corps resumes advance north. |

| 24 Nov | Eighth Army moves north from the Ch’ongch’on River. |

| 25 Nov | Chinese forces attack Eighth Army center and right. |

| 27 Nov | X Corps attacks from west in support of Eighth Army; Chinese forces strike X Corps at Chosin Reservoir. |

| 29 Nov | Eighth Army begins general withdrawal from Ch’ongch’on River line to defensive line at P'yongyang. |

| 29 Nov– 1 Dec | Chinese forces devastate U.S. 2d Infantry Division as it guards Eighth Army withdrawal. |

| 30 Nov | X Corps starts retreat to port of Hungnam. |

| 5 Dec | Eighth Army falls back from P’yongyang. |

| 11–24 Dec | X Corps loads on ships for evacuation to Pusan; General Almond sails on Christmas Eve. |

| 23 Dec | General Walker is killed in auto accident north of Seoul. |

| 26 Dec | Lt. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway arrives in Korea as Eighth Army commander. |

| 31 Dec – 5 Jan | New CCF offensive begins. |

| 4 Jan | Seoul falls; Eighth Army pulls back to line forty miles south of Seoul. |

| 5 Jan | Port of Inch’on is abandoned. |

| 7–15 Jan | Enemy offensive subsides; UNC situation stabilizes— intelligence sources report many enemy units had withdrawn to refit. |

| 15 Jan | Army Chief of Staff General J. Lawton Collins, on a visit to Korea, declares that “we are going to stay and fight.” |

The second phase of the Korean War, the UN Offensive, had been a story of relentless military success against the North Korean People’s Army. The capture of a Chinese soldier on 25 October 1950, however, marked a fundamental change in the nature of the conflict. When the presence in North Korea of Communist Chinese Forces (CCF) units was confirmed, there was much debate in the United Nations Command (UNC) and in Washington about China’s intentions, but that presence was quickly felt on the battlefield.

In the X Corps zone Chinese forces in late October had stopped a Republic of Korea (ROK) column advancing on the Changjin (Chosin) Reservoir. On 2 November the U.S. 7th Marines relieved the South Koreans and over the next four days broke through the Chinese resistance to within a few miles of the reservoir, at which point the Chinese broke contact. In the west, the Eighth Army fell back under attack to the Ch’ongch’on River, though the Chinese again broke contact after 6 November. By then three CCF divisions (10,000 men each) were estimated to be in the Eighth Army sector and two in the X Corps zone. UN pilots were also for the first time encountering Russianmade MIG–15 jet fighters.

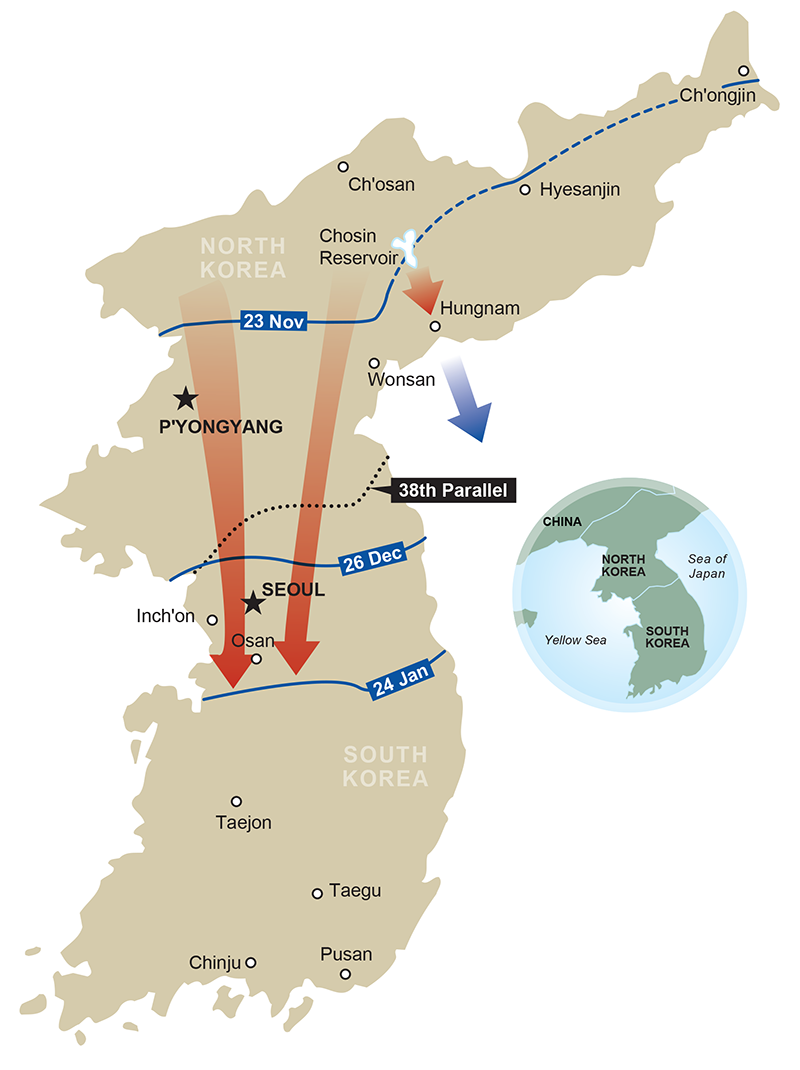

After 6 November a comparative lull lasted for several weeks. Estimates of CCF strength rose through the month, but General Douglas MacArthur, the UNC commander, felt that the Chinese were not strong enough to launch an all-out offensive, particularly when North Korean's forces were battered and ineffective. He thus prepared to press on with his plans to reach the Yalu River. Moreover, MacArthur said, there was no other way to obtain "an accurate measure of enemy strength." Lt. Gen. Walton H. Walker's Eight Army was to move northward through western and central Korea, while Maj. Gen. Edward M. Almond's separate X Corps, now strengthened by the arrival of the 3d Infantry Division from the United States, was to move from northeastern Korea northwest to cut enemy lines of communication and support the Eighth Army. After taking time to improve his logistical support, Walker launched his offensive on 24 November. At first the Eighth Army encountered little opposition, but the next night the enemy launched a fierce counterattack in the mountainous terrain near the central North Korean town of Tokch'on. The X Corps, which had resumed its advance earlier, joined the planned attack on 27 November, moving slowly, but that evening a second enemy force, moving down the Chosin Reservoir, struck the 1st Marine Division and elements of the U.S. 7th Division.

It was clear that most of the enemy were Chinese, but the surprise was the size of the two attacking forces. By 28 November MacArthur had his “accurate measure” of the enemy’s strength: the Chinese XIII Army Group, with some 200,000 troops, faced the Eighth Army; the IX Army Group, with 100,000 men, faced X Corps. Both had slipped into North Korea from Manchuria largely undetected. On the 28th MacArthur informed Washington that “we face an entirely new war,” and the next day he instructed General Walker to withdraw as necessary to escape being enveloped by the Chinese. He also ordered X Corps to pull back into a beachhead at the east coast port of Hungnam, north of Wonsan.

The main enemy attack in the Eighth Army zone was directed against the ROK II Corps. When the Chinese broke through the UN line, General Walker committed his reserves (the U.S. 1st Cavalry Division, the Turkish Brigade, and the British 27th Commonwealth and 29th Independent Infantry Brigades), but they failed to stop the repeated wave of enemy troops. Walker first withdrew south across the Ch’ongch’on River, suffering heavy casualties. The U.S. 2d Division fought a delaying action while other units regrouped in defensive positions near the North Korean capital of P’yongyang. On 5 December the Eighth Army fell back to positions about twenty-five miles south of that city, and by mid-December it had moved below the 38th Parallel to form a defensive perimeter north and east of Seoul, the South Korean capital. At the same time, in early December, MacArthur ordered X Corps to evacuate by sea to Pusan, where it would become part of the Eighth Army. December thus saw the loss of all UNC territorial gains in North Korea.

By this time the UNC included troops from fifteen countries, but the sense of crisis in the command was heightened by the death of General Walker in an auto accident north of Seoul on 23 December. Lt. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway replaced him, arriving in Korea on 26 December. Ridgway was determined to maintain the existing line above Seoul, but on 30 December MacArthur told the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) that the Chinese could drive the UNC out of Korea unless he received major reinforcement. He also proposed air and naval attacks on mainland China and the involvement of Chinese Nationalist forces. None of his demands and proposals were accepted. Washington was not prepared to let the conflict in Korea escalate into a larger war. President Harry S. Truman’s more pressing concern was the global intentions of the USSR. The JCS told MacArthur to stay in Korea if he could but to prepare to withdraw to Japan if necessary.

On the other hand, despite a renewed enemy offensive that started on 31 December and saw the abandonment of Seoul on 4 January 1951, General Ridgway became increasingly convinced that his existing forces were sufficient. He noted that the Chinese did not aggressively push south after marching into Seoul and that North Korean forces ceased their offensive in central and eastern Korea by mid-January. He concluded that a rudimentary logistical system constrained enemy offensive operations to no more than a week or two. Tactically his goal was thus to “wage a war of maneuver—slashing at the enemy when he withdraws and fighting delaying tactics when he attacks.” When General J. Lawton Collins, Army Chief of Staff, visited Korea, he agreed with Ridgway. “As of now,” Collins announced on 15 January, “we are going to stay and fight.”

As the third phase of the Korean conflict drew to an end, General MacArthur gave Ridgway unprecedented authority to plan and execute operations in Korea. Ridgway, in turn, was poised to return to the offensive.