The Korean War: Phase 5

9 July 1951–27 July 1953

Courtesy of the Center of Military History

Republished by the USASOC History Office, August 2020

Chronology

| 10 Jul 51 | Armistice talks begin at Kaesong. |

| 23 Aug | Communist side breaks off negotiations. |

| 5 Sep | North Koreans abandon Bloody Ridge, after UN forces, led by U.S. 2d Infantry Division’s 9th Infantry, outflank it. |

| 12 Sep– 13 Oct | 2d Infantry Division, using the 72d Tank Battalion to tactical advantage, seizes Heartbreak Ridge. |

| 3–19 Oct | Five UN divisions advance to Line Jamestown, some four miles beyond the Wyoming line, to protect the Seoul-Ch’orwon railway. |

| 25 Oct | Armistice talks resume, now at P’anmunjom. |

| 12 Nov | General Ridgway, the UNC commander, instructs General Van Fleet to cease Eighth Army offensive operations and to assume an “active defense.” |

| 12 May 52 | General Mark W. Clark assumes command of the UNC. |

| 8 Oct | UN delegation calls an indefinite recess to armistice talks, reflecting a long lack of any progress. |

| 11 Feb 53 | Lt. Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor takes command of the Eighth Army. |

| 26 Apr | Armistice talks begin again. |

| 6–11 Jul | General Taylor abandons Pork Chop Hill, a 7th Infantry Division outpost, to the Chinese as not worth further fighting. |

| 13–20 Jul | Chinese launch a six-division attack against ROK II Corps and U.S. IX Corps south of Kumsong; after falling back some eight miles to below the Kumsong River, UN forces regain the high ground along the river. |

| 27 Jul | Armistice agreement is signed at 1000; all fighting stops twelve hours later; both sides have three days to withdraw two kilometers from the cease-fire line. |

Armistice talks began at Kaesong on 10 July 1951. North and South Korea were willing to fight on, but after twelve months of large-scale but indecisive conflict, their Cold War supporters—the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union on one side, the United States and its UN allies on the other—had concluded it was not in their respective interests to continue. The chief negotiator for the UN was American Vice Adm. C. Turner Joy; his counterpart was Lt. Gen. Nam Il, the chief of staff of the North Korean People’s Army. At the first session it was agreed that military operations could continue until an armistice agreement was actually signed. The front lines remained relatively quiet, though, as the opposing sides adopted a cautious watch-and-wait stance.

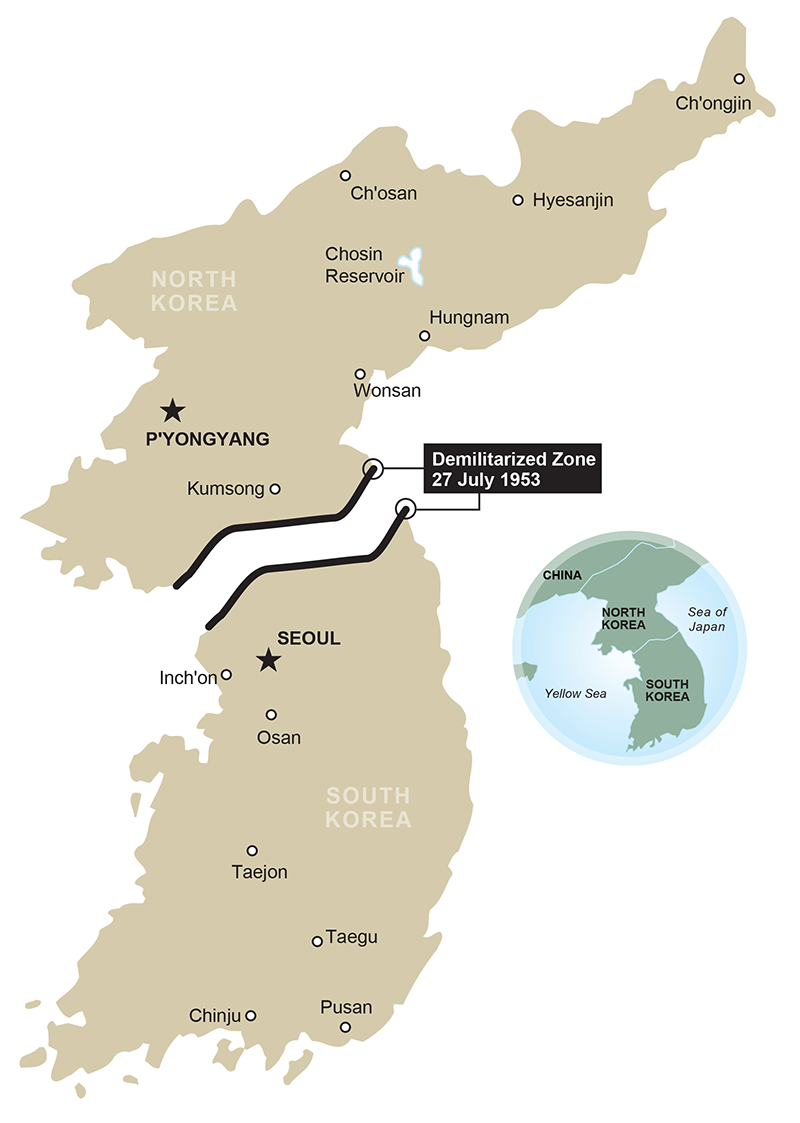

Lt. Gen. James A. Van Fleet’s Eighth Army had fortified its positions along Line Kansas and along Line Wyoming, a bulge north of Kansas in the west-central area known as the Iron Triangle. Both the Kansas line in the east and the Wyoming bulge were above the 38th Parallel, the prewar boundary between the two Koreas. On the west, the front line dipped below the 38th Parallel north of Seoul, the South Korean capital, and then continued to fall toward the coast. This uneven line led to the first impasse in negotiations, when the North Korean and Chinese side argued that the armistice line should be the 38th Parallel, while the UN negotiators called for a line reflecting current positions, which they argued were more defensible and secure than the old border.

When the Communist side broke off negotiations on 23 August, General Matthew B. Ridgway’s United Nations Command (UNC) responded with a limited new offensive. General Van Fleet sent the U.S. X Corps and the Republic of Korea (ROK) I Corps to gain terrain objectives in east-central Korea five to seven miles north of Kansas—among them places that resonate with veterans, such as the Punchbowl, Bloody Ridge, and Heartbreak Ridge. In the west, five UN divisions (the ROK 1st, the 1st British Commonwealth, and the U.S. 1st Cavalry and 3d and 25th Infantry) struck northwest along a forty-mile front to secure a new position beyond the Wyoming line to protect the vital Seoul-Ch’orwon railway. The U.S. IX Corps followed by driving even farther north to the edge of Kumsong.

By the last week of October the UN’s objectives had been secured, and on the 25th the armistice talks resumed—now at P’anmunjom, a hamlet six miles east of Kaesong. When the North Koreans and Chinese dropped their demand that the armistice line be the 38th Parallel, the two sides agreed on 27 November that the armistice demarcation line would be the existing line of contact, provided that an armistice agreement was reached in thirty days. A lull now settled over the battlefield, as fighting tapered off to patrols, small raids, and small unit (but often bitterly fought) struggles for outpost positions. When the thirty-day deadline came and went, as negotiations stalled over the exchange of prisoners of war, among other issues, both sides tacitly extended their acceptance of the armistice line agreement. The continuing absence of large-scale combat allowed the UNC to make several battlefield adjustments, withdrawing the U.S. 1st Cavalry and 24th Infantry Divisions from Korea between December 1951 and February 1952 and replacing them with the 40th and 45th Infantry Divisions, the first National Guard divisions to serve in the war. General Van Fleet also shifted UN units along the front in the spring of 1952, giving more defensive responsibility to the ROK Army in order to concentrate greater U.S. strength in the west.

Meanwhile, the Far East Air Forces intensified a bombing campaign begun in August 1951, supported by U.S. naval fire and carrier-based aircraft. In August 1952 the largest air raid of the war was carried out against P’yongyang, the North Korean capital. Both sides exchanged heavy artillery fire through 1952, and in June the 45th Division, in response to increased Chinese ground action, engaged in an intense period of fighting with the Chinese, successfully establishing eleven new patrol bases along its front. By the beginning of 1953, however, the larger picture was still one of continuing military stalemate, with few changes in the front lines, reflecting the deadlock in the armistice talks that had led the UN delegation to call an indefinite recess in October 1952.

Lt. Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor took command of the Eighth Army on 11 February 1953. By March he was faced with renewed enemy attacks against his frontline outposts. Despite the fact that the armistice talks had resumed on 26 April, accompanied by a major exchange of sick and wounded UN and enemy prisoners, flare-ups occurred again in late May and on 10 June, when three Chinese divisions attacked the ROK II Corps defending the UN forward position just south of Kumsong. By 18 June the terms of a final armistice agreement were almost settled, but when South Korean President Syngman Rhee unilaterally allowed some 27,000 North Korean prisoners who had expressed a desire to stay in the South to “escape,” the final settlement was further delayed. The Chinese seized on this delay to begin a new offensive to try to improve their final front line. On 6 July they launched an attack on Pork Chop Hill, a 7th Division outpost, and on the 13th they again attacked the ROK II Corps south of Kumsong (as well as the right flank of the IX Corps), forcing the UN forces to withdraw about eight miles, to below the Kumsong River. By 20 July, however, the Eighth Army had retaken the high ground along the river, where it established a new defensive line.

As the UN counterattack was ending, the P’anmunjom negotiators reached an overall agreement on 19 July. After settling remaining details, they signed the armistice agreement at 10 o’clock on the morning of 27 July. All fighting stopped twelve hours later. The cease-fire demarcation line approximated the final front. It ranged from forty miles above the 38th Parallel on the east coast to twenty miles below the parallel on the west coast. It was slightly more favorable to North Korea than the tentative armistice line of November 1951, but compared to the prewar boundary, it amounted to a North Korean net loss of some 1,500 square miles. Within three days of signing both sides were required to withdraw two kilometers from the cease-fire line. The resulting demilitarized zone has been an uneasy reality in international relations ever since.