DOWNLOAD

In November 1946, a U.S. Army combat infantry battalion commander, somewhat bored with postwar Occupation duty, volunteered for the 7734th Historical Detachment. Charged with interviewing captured German senior officers, Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Theodore C. Mataxis (Sidebar: The Mataxis Legacy), a National Guard officer from Seattle, Washington, formed a lifelong professional relationship with SS Major (MAJ) Otto Skorzeny. It was he who located and rescued the Italian Il Duce, Benito Mussolini, from his captivity on the Gran Sasso. LTC Mataxis, personally fascinated by this special operations mission, assisted in the debriefing of the “Commando Extraordinary” and his adjutant, MAJ Karl Radl.1 The two were among the many senior officers being held in the Oberursel POW Camp in 1947, after being exonerated of war crimes by the Allied tribunal at Nurnberg. An inveterate professional ‘pack rat,’ LTC Mataxis kept a carbon paper copy of the original Gran Sasso interview. His son, LTC (ret) Theodore C. Mataxis Jr, shared that copy with the USASOC History Office.

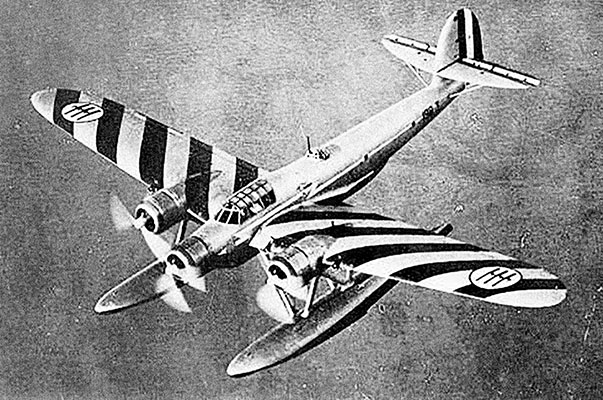

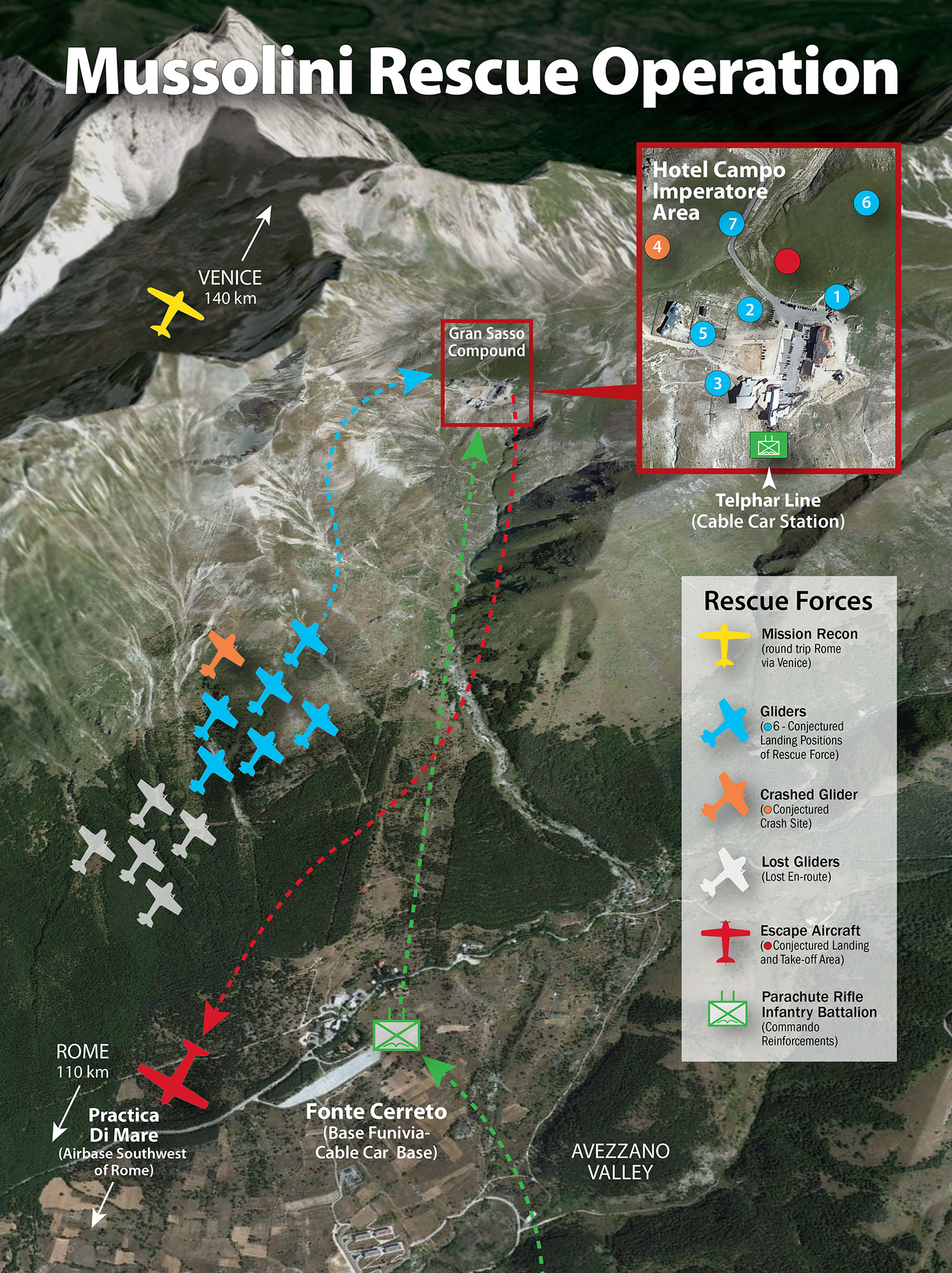

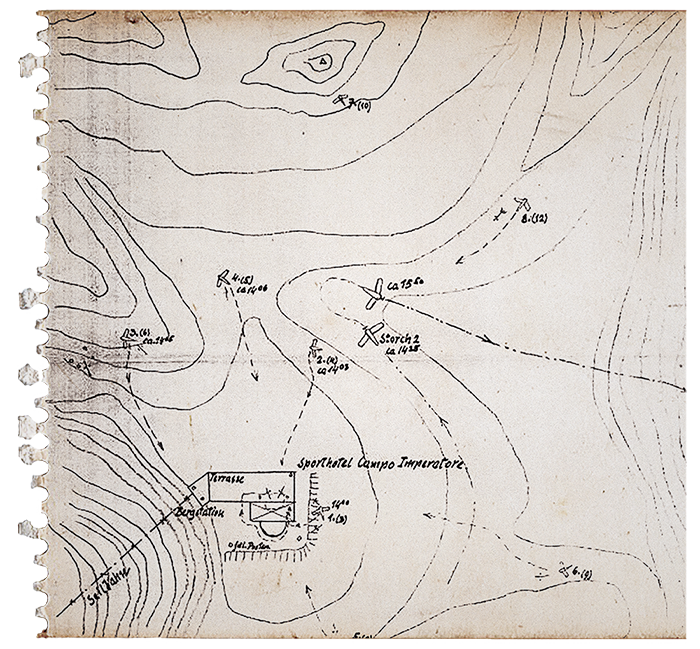

The purpose of this collective essay is to graphically illustrate the Adolf Hitler-dictated rescue using period Bundesarkive photographs of the operation and rescue aircraft. It required considerable ‘manhunting’ to find Il Duce after he was secreted away on 25 July 1943 by the Italian national police. These Carabinieri were acting under orders from the Italian King Victor Emmanuel III. With Rome under Allied attack, King Victor Emmanuel was anxious to break ties with Germany and gain an armistice. Disinformation masked Mussolini’s disposition. Germany scrambled to reinforce Italy after the Allied invasion at Salerno on 3 September 1943. Allied air superiority complicated the secret rescue operation. Mussolini was positively located on the Gran Sasso days before the Italian king announced an armistice. A fortnight later MAJ Skorzeny’s airborne commandos swept down upon the alpine ‘prison.’ The surprise rescue of Il Duce proved to be a major Nazi Psywar coup that boosted military and civilian morale. It was true to the motto of Britain’s 22nd Special Air Service (22 SAS), “Who dares, wins”—the critical element of success in special operations.