DOWNLOAD

The purpose of this analytical historical commentary is to provide sufficient background and context before explaining the personnel recovery mission done in Iran by 10th Special Forces Group (SFG) in May 1962. That is the subject of the following article, “10th SFG Mountain Recovery Operation – Iran 1962.” So, why was this significant? It was the first operational mission assigned to 10th SFG by U.S. Army Europe (USAREUR).

Because the era spanning 1952 into the early 1960s was a very conflicted period in American history, it is important to review the world situation, the growing Cold War, the internal challenges facing America, and the state of the Army at home and overseas after the Korean and Second World Wars. Factoring these elements with the WWII combat experiences of our Army special operations (ARSOF) leaders during that period will explain why Special Forces (SF) was marginalized by the conventional Army before John F. Kennedy became president. The mythology about the ‘good ole’ days of SF will be debunked. But, we have to start at the beginning in 1952.

The concept of ‘special forces’ was developed and approved by the Army Staff based on the persistent efforts of Brigadier General (BG) Robert A. McClure, the Chief of Psychological Warfare (CPW), our “Father of Special Warfare.” His primary action officer was Colonel (COL) Russell W. Volckmann, the Philippine guerrilla commander who authored Field Manual (FM) 31-21: Organization and Conduct of Guerrilla Warfare, October 1951. Organization, training, and fielding of Special Forces (SF) would be accomplished by the U.S. Army Psychological Warfare (Psywar) Center.

Colonel (COL) Charles H. Karlstad, the Chief of Staff, U.S. Army Infantry Center, Fort Benning, GA, was called to the Pentagon in May 1952 to receive guidance from BG McClure. COL Karlstad had been selected to command the Army Psywar Center being activated at Fort Bragg, NC, in accordance with General Orders No. 37, Section IV. Lieutenant Colonel Otis E. Hays, Jr., the former Director of Psywar at the Army General School, Fort Riley, KS, was to be the first Director of the Psychological Operations (PSYOP) Department effective 29 May 1952. COL Aaron Bank, an OSS veteran on McClure’s staff, was the first Director of the Special Forces (SF) Department.1

The manpower slots to create the Psywar Center headquarters and SF were ‘harvested’ from Ranger infantry companies deactivated during the Korean War. Special Forces were to be organized, trained, and deployed overseas early in the administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower (1952-1960). In late 1953, ninety-nine SF-trained officers and sergeants had been assigned to Korea and the 10th SF Group (SFG) shipped out to Germany. These two SF overseas movements coincided with an exponential growth of the Cold War triggered by nuclear weapons.

America’s postwar dominance of the world as the nuclear superpower ended four years to the month after the atomic bombing (A-bombs) of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, in August 1945. A Soviet A-bomb in 1949 created nuclear parity and brought superpower status. Atomic parity ended in November 1952 when the US exploded a hydrogen bomb (H-bomb). Parity was regained three years later when the Soviets got their H-bomb. The Cold War arms race escalated with long range nuclear-warhead missiles. Multiple nuclear weapon delivery systems were vital to avoid a one-shot knockout blow from the enemy as Communism spread further in Asia.

America became enraptured in a second Red Scare (the first occurred after WWI when the Communist Reds wrested control of Russia from the Whites) and after Mao Tse-tung and the Chinese Communists drove the Nationalists from the mainland in 1949. To add fuel to the Red Scare the Chinese intervened in Korea in late November 1950. It had already taken several years to push the Russians out of the Axis-occupied countries of Western Europe and end Communist-supported upheaval in Greece. With U.S. ground forces a small fraction of WWII levels (more than ninety divisions) President Eisenhower reinforced bipartisan anti-Communism as national policy by making Nuclear Deterrence and Mutual Assured Destruction U.S. defense strategy.

In the center of the Arms Race with the Soviets delivery of nuclear weapons became the top priority for research and development. Guided ballistic missiles, medium and long-range jet bombers [the U.S. Air Force (USAF) became a separate service in 1947] that could be refueled in the air, and nuclear-powered submarines armed with nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles capable of hiding under polar ice for months were the goals. The USAF Strategic Air (SAC) and Missile Commands dominated American defense spending after post-Korean War military reductions. Munitions for medium and heavy artillery and engineer cratering demolitions were enhanced with nuclear warheads. In Europe the Army fielded the M-65 280mm atomic cannon that could fire a 550-pound projectile 20 miles.2 Offensive and defensive tactics changed markedly as the nuclear enhanced munitions were adapted to fit all environments of warfare—air, sea, and land. Defense-oriented electronic warfare was still in its infancy.

Military force reductions after WWII and Korea left battlefields (defense of Western Europe primarily) to a much smaller Army adapting its tactics to nuclear weaponry. Combat power in the 900,000 soldier Army was contained in fifteen ‘Pentomic’ [pentagon (5 battle groups) + atomic)] divisions. Infantry and armored battle groups [strengths similar to the regimental combat teams (RCTs) in the Korean War or today’s light infantry brigade combat teams (BCTs)] formed the core of the fighting divisions.

This discussion focuses on Europe where five ‘Pentomic’ armored and mechanized infantry divisions and one Special Forces group were stationed. They were to delay massive Soviet armored attacks launched after nuclear artillery, rocket, and missile preparations. All ‘Pentomic’ divisions had tactical guided nuclear warhead rockets (the jeep-mounted Davy Crockett rocket systems with 2.5 mile ranges) and truck-mobile Honest John missiles – 14 miles). U.S. armored and mechanized infantry divisions had nuclear warheads for medium artillery as well as atomic demolitions. West European allies also furnished combat divisions.

Similarly-armed West German, British, and French divisions reinforced America’s five ‘Pentomics’ in the first line of defense against a Soviet attack into Europe. The two ‘Pentomic’ airborne divisions were in strategic reserve in the States. Annually, an airborne infantry battle group (alternated between the 82nd and 11th Airborne Divisions) deployed (‘gyro-scoped’) to Germany for a year to demonstrate Army strategic readiness. The reality was that the Allied forces were outnumbered five to one by the Russian and Eastern Bloc militaries. The Army and Air Force also had roles in the second line of defense.

Air defense and medium range ballistic missiles formed the second defense line. Army Nike Hercules and Hawk air defense missile systems guarded American skies as well as those of allies worldwide. Air Force strategic medium range ballistic missiles (MRBM), Jupiters, having a 1,500 mile range, were statically positioned as far as Turkey as well as on Taiwan (Nationalist China) and in South Korea. Three long-range strategic nuclear weapons systems reinforced the first two lines of defense.

SAC bombers carried nuclear bombs and Air Force intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) stood ready in underground silos across America at the same time nuclear-powered Navy submarines with atomic weapons prowled underwater off Soviet seacoasts. The strategic forces progressed to airborne, ground, and underwater 24/7 alert to counter Soviet ICBMs and long-range bomber attacks. The SAC jet tanker fleet stayed airborne with the bombers. At the same time strategic high altitude photo reconnaissance aircraft overflew Soviet missile sites and military bases to provide early warning.

Francis G. ‘Gary’ Powers

After a high-altitude U-2 Dragon Lady reconnaissance plane was shot down on 1 May 1960, a very bellicose Soviet premier Nikita S. Khrushchev had hard evidence of American ‘spy’ missions that regularly ‘invaded Soviet airspace.’ Photos of the contract pilot, Francis G. ‘Gary’ Powers, and his crashed aircraft, made newspaper front pages around the world. The U-2 shoot down was sufficient to cancel summit talks in Vienna, Austria, with President Eisenhower. That the Soviets possessed an air defense missile that could reach U-2 operational altitudes came as a big surprise and segues into how the 34th U.S. President dealt with ‘brushfire’ wars that affected American interests.

President Eisenhower relied on Allen W. Dulles and the CIA to resolve these problems. Special Forces became CIA surrogate advisor trainers to friendly indigenous elements, initially in Laos, and then also in South Vietnam. SF operational detachments alpha and bravo (ODAs and ODB command & control elements) were sent overseas on temporary duty (TDY) from 1st SFG on Okinawa and 77th SFG (which became 7th SFG) at Fort Bragg, NC, up to 180 days. The SF teams had little contact with U.S. Military Advisory Assistance Groups (MAAGs) overseas. Meanwhile, the Russians were imposing discipline in the Eastern Bloc countries.

US-sponsored Radio Free Europe broadcasts that encouraged uprisings behind the Iron Curtain ended shortly after Soviet tanks crushed the Hungarian Revolution in 1956. Washington simply watched and then embarrassedly granted asylum to the ‘patriots.’3 Ironically, this was a time when there were three airborne battle groups, one in Augsburg and two in Mainz, and the 10th SFG in Bad Toelz.4 That same year President Eisenhower appealed to the United Nations (UN) to force the withdrawal of Israeli, French, and British forces from the Suez after Egypt’s Abdel Gamal Nasser nationalized the canal. Postwar colonial independence movements spread from Palestine to north and central Africa and into the Middle East.

Knowing the situational dynamics that impacted on Special Forces in its first decade of existence, one can better understand why it was marginalized by conventional Army commands in Europe during ‘the good ole’ days of SF.’ First, ground defense of Western Europe had been the Army’s top priority since WWII. Second, based on the Soviet armor threat that mission was assigned to conventional combat heavy forces, especially in the postwar nuclear environment in which the Air Force and Navy were key to strategic defense and nuclear retaliation. Third, with ground defense tied to armor and mechanized divisions Army veterans of the European Theater Operations (ETO) in WWII were most familiar with that type of warfare. Few Army SOF icons possessed those credentials.

Only Colonel Charles H. Karlstad, the first U.S. Army Psychological Warfare (Psywar) Center commander, had that pedigree. The WWI combat infantryman rose from major (MAJ) to brigadier general (BG) fighting Panzer forces across Europe in the 14th Armored Division. While BG Robert A. McClure was another WWII and ETO veteran, he was General Eisenhower’s Chief of Psywar. COL Aaron Bank, the ‘Father of SF’ and the first 10th SFG commander, served short tours in Europe and Asia while detailed to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). COL Edson D. Raff, who succeeded Karlstad at the Psywar Center, like the majority of those commanders following him and COL Bank well past the 1960s, were WWII paratroopers and infantrymen.

Throughout WWII and the Korean War, airborne divisions and regimental combat teams and Ranger units were regarded as strategic theater assets. They were committed to specific key, short duration missions. They were withdrawn to rear areas to reconstitute and prepare for future ‘spearhead’ missions. Like the airborne the OSS operational elements in Europe performed short term combat missions. Conventional Army senior leaders resented the OSS, the airborne, and the Rangers because they had a high priority for personnel and constantly recruited the best officers and soldiers who were the ‘backbone’ of wartime fighting forces.

Conventional line units slugged it out day and night in all weather, year after year with determined, combat-hardened German, Italian, Japanese, North Korean, and then, Communist Chinese defenders. Strategic forces, the prima donas, did not. Naturally, attitudes developed and became prevalent among senior Army leaders which created a lasting schism. The SF reaction to ‘Big Army’ USAREUR was to adopt a super elitist posture and align with the airborne. But, the biggest hurdle to acceptance by Army leaders in USAREUR was that the SF planned ‘to fight the last war’ in a nuclear age after the Communist countries had ‘locked down’ their societies.

To compound disparities with ‘heavy’ Army in Europe, SF operated using OSS doctrine, tactics, and techniques of 1944.5 The guerrilla advisory role performed in Korea (1953-1954) by almost a hundred SF officers and sergeants was never inculcated in SF training. The fact that all cross-border operations into North Korea were failures was likewise ignored.6 **Note: SF did not get its Special Atomic Demolition Munition (SADM) mission until 1962.7

COL Bank proselytized that 10th SFG would launch airborne OSS-like ‘behind the lines’ missions into the Soviet Union from France. Painfully aware that the Soviet Bloc ground and air forces outnumbered them five to one, American armor and mechanized infantry leaders thought Special Forces would contribute nothing to a short-lived fight involving nuclear weapons. They anticipated that theirs would probably be a two-week delaying action. To them SF was ignoring the realities of modern war and the capability of Americans to survive ‘behind the Iron Curtain.’8 Contrastingly, Psywar units sent to Germany, the 5th Loudspeaker & Leaflet (L&L) Company and US Army Reserve 301st Radio Broadcasting & Leaflet (RB&L) Group, were well received. Psywarriors had fought alongside ETO conventional forces to win the war in Europe.

So, what ‘value added’ could 800 Special Forces soldiers provide USAREUR? Much smaller than a battle group with negligible fire power, they proved to be a godsend after post-Korean War reductions-in-force (RIFs) eroded operational readiness in Europe. The sudden influx of non-commissioned officers (NCOs) who reverted from reserve officer ranks of 10th SFG, fixed key USAREUR personnel shortages. But, the RIF also gutted the SF of combat experience, cut strength 30 percent, and reduced 10th SFG to two companies.9 By then COL Bank was long gone from his succeeding assignment as the USAREUR G-3 Plans Officer.

His successor twice removed, the highly decorated COL Michael ‘Iron Mike’ Paulick, did not improve the image of SF among the European senior officers. His practice of ‘button holing’ USAREUR generals after Seventh Army NCO Academy graduations came to an end with Lieutenant General (LTG) Paul D. Adams. When a green beret bearing three stars was placed on the head of the unsuspecting V Corps commander (former executive officer of the WWII First Special Service Force [FSSF]), LTG Adams angrily ripped it off, flung the beret at COL Paulick, and stormed out.10 To compound SF integration problems in USAREUR G-3 Plans, that paid parachute position was regularly filled by airborne officers knowing little about Special Forces.

Thus, special warfare annexes to the USAREUR war plans read like vague contingency plans (CONPLANs). SF employment in field exercises was consistently notional. Typically the 10th SFG furnished aggressors for corps and division maneuvers. SF teams regularly ‘infiltrated’ command posts to upset senior commanders.11 Consistent with WWII OSS TTPs, SF conducted elaborate escape and evasion ‘rat line’ exercises for NATO pilots and aircrews. Personnel with problems were usually shipped to Berlin.12 The heavy Army ruled Europe. While regularly put ‘on alert’ in Flint Kaserne few SF operational deployments occurred.

The 10th SFG was put on alert with USAREUR during the 1956 Hungarian Uprising as well as the Suez Crisis and during those in Berlin and Beirut in 1958. However, SF never went beyond that stage. It was the ‘gyro-scoped’ 11th Airborne Division battle group from Augsburg, Germany, that joined two U.S. Marine Corps (USMC) battalion landing teams (BLTs) in Beirut. The paratroopers opened the airport and restored a semblance of peace in Lebanon (July-October 1958). During the Congo Crisis in 1960, three 10th SFG soldiers clandestinely coordinated air evacuation of 3,000 European refugees. This very successful operation was not publicized.13

It was President John F. Kennedy (1961-1963) and his Secretary of Defense, Robert S. McNamara, who expanded national security strategy to cover the broader spectrum of conflict. Kennedy’s ‘flexible response’ covered the gamut from nuclear war to countering insurgency and assisting new countries combat Communist-inspired ‘wars of national liberation.’ America’s armed forces were to be reshaped to accommodate special warfare. The Army’s Special Forces were to have key roles.14 Premier Kruschchev became a ‘constant thorn’ to President Kennedy after the CIA-contrived Cuban Bay of Pigs invasion turned into a fiasco in April 1961.

Denying access to the Western zones in August 1961 proved to be an escalation of earlier Soviet-instigated challenges in occupied Berlin. A week after the East Germans began erecting barbed wire barriers to block egress from the Russian sector, President Kennedy dispatched his Vice President, Lyndon B. Johnson, to the divided city to emphasize White House concerns. On Saturday, 19 August 1961 Vice President Johnson’s arrival at Templehof Airport was greeted by an American military honor guard. He was to give two reassuring speeches to a large crowd of Berliners outside the City Hall and the House of Representatives inside. The Vice President had already spent the previous afternoon and evening with West German officials in Bonn.15

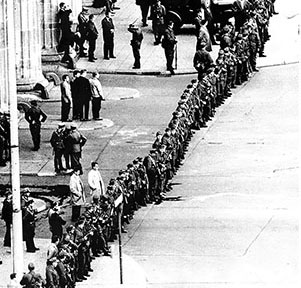

At 10:30 AM on Sunday, 20 August, Vice President Johnson was waiting at the border of the Western Sector to welcome Colonel (COL) Glover S. Johns, Jr. who was leading the 1st Battle Group, 18th Infantry [8th Infantry Division (8th ID)] from Mannheim, West Germany. For two days the mechanized infantry (1,600 men) had convoyed 500 vehicles and rolling stock on the autobahn. Berliners watching their arrival were disappointed by the small number of tanks that accompanied them; ‘Pentomic’ divisions had a single armor battalion; the 1st Battle Group got a tank company. The 8th ID mechanized battle group demonstrated U.S. resolve. All convoy serials went unchallenged by the Soviet check points. After talking with COL Johns for a few minutes the vice president mingled with the soldiers, welcoming them to Berlin.16

Accompanied by retired General Lucius D. Clay, the respected former military governor, Vice President Johnson was briefed by British, French, and American commanders in Berlin.17 Allegedly, when the 10th SFG detachment explained that their mission was to organize resistance in Soviet bloc countries, the vice president suggested that SF might better be oriented towards the Middle East. Regardless of the source, this became the justification to reorganize the 10th SFG in Germany.18

The understrength Tenth, two companies since the mid-1950s, internally reorganized to stand up a third company focused on North Africa and the Middle East. The task fell to Major (MAJ) Charles M. Simpson III, the Group S-3. MAJ Simpson had been the Middle East history professor at West Point after a summer of graduate studies at the American University in Beirut. Though Simpson had just commanded an SF company, he volunteered to form the new unit.19 Captain (CPT) Herbert Y. Schandler, a Military Academy colleague, was an ODA commander. Previously oriented towards Poland, ODA 33 was refocused on Iran, and two men were sent off to learn Farsi.20 Back in the States, President John F. Kennedy was directing his military service chiefs to inculcate special warfare into their mission sets.

The first sidebar explains what happened after President Kennedy did this and the impact on Special Forces. The second sidebar details the measures taken by Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy to keep the Shah of Iran from declaring his country ‘non-aligned’—the critical opening for Soviet assistance. Alliances were crucial to halt the spread of Communist influence.

In Summary

Demonstrating the relevance of Special Warfare, Special Forces, and Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF) to the Army and their evolving national security roles is a continual challenge. That responsibility rests on the credibility of ARSOF leaders at all levels working with the vast majority of conventional Army leaders who dominate the Officer Corps. SF has always promulgated tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) and doctrine intimately tied to the WWII OSS.

In 1962, seventeen years after the U.S. military embraced nuclear weapons to defend Europe, SF got its only nuclear weapon. The Special Atomic Demolition Munitions (SADM) was a one-way, soldier delivery mission.28 Interdependence, interoperability, and integration, practiced overseas today, were absent from SF vocabulary until the late 1970s. True integration requires flexibility, agility to adjust from supported to supporting, and a solid understanding of conventional Army doctrine, tactics and operational readiness standards. This is what is required to demonstrate ‘value added’ to conventional warfighters.

SF credibility in the 1950s and early 1960s was hurt by leaders short on conventional Army combat experience. Promulgating WWII–era unconventional warfare (UW) doctrine and TTPs as its combat role in nuclear age warfighting did not help. Disregarding societal controls (homeland security) inherent with paranoid Communism, SF cultural and situational awareness became locked into a 1944 world of enemy-occupied ‘free’ countries. Ironically, these same conclusions were articulated in 1983 by retired SF Colonels Robert B. Rheault and Charles M. Simpson III and LTG William P. Yarborough, a major ARSOF icon, in his foreword to Inside the Green Berets: The First Thirty Years: A History of U.S. Army Special Forces. Notwithstanding, this historical analysis commentary should place the significance of the 10th SFG mission to Iran in May 1962 in perspective.

The 10th SFG grabbed the 1962 operational mission detailed in the following article. It was a significant task that afforded an orientation to Iran. Though the assignment was not an exciting ‘blood and guts,’ highly classified, combat mission ‘behind enemy lines,’ the Tenth leadership realized that it could be a ‘door opener’ to a key Middle Eastern country that was critical to the United States in the Cold War against Communism.