ABSTRACT

Formed in 1986, the 112th Signal Battalion first experienced combat in Panama, during Operation JUST CAUSE, December 1989. Their support to Special Operations Command, South, validated the need for a dedicated Army Special Operations signal battalion.

TAKEAWAYS

- The 112th Signal Battalion was created as an expeditionary unit, able to provide dedicated communications to SOF headquarters in two theaters simultaneously.

- Five SOCA teams provided SOCSOUTH secure communications during Operation JUST CAUSE; two additional SOCAs supported civil-military operations during PROMOTE LIBERTY.

- Due to the short duration of JUST CAUSE, the 112th Signal Battalion’s large multichannel satellite terminals were not needed in Panama. It was truly SOCA-led war.

DOWNLOAD

In memory of COL (Ret.) Steven R. Sawdey, the second Commander, 112th Signal Battalion, who passed away on 20 November 2019. He generously shared his recollections of the 112th, and its role in JUST CAUSE and PROMOTE LIBERTY, with the author. He is remembered fondly by those who served with him, and especially by the 'Shadow Warriors' he led from 1988 to 1990.

Bullets ripped through Hangar 450 at Albrook Air Station, Panama, in the late evening of 19 December 1989, just as U.S. Army Special Forces Major (MAJ) Kevin M. Higgins and his Company A, 3rd Battalion, 7th Special Forces Group (A/3-7th SFG) prepared to depart for their H-Hour target: the Pacora River Bridge.1 “We lifted off to go to the fight,” Higgins explained, “but the fight had come to the men at the hangar.”2 Two of them were Staff Sergeant (SSG) Henry N. McCrae and Sergeant (SGT) Steven I. Elizalde, from the 112th Signal Battalion (Airborne), one of the newest Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF) units.3 Their small signal element, consisting of two, three-man Special Operations Communications Assemblage (SOCA) teams, was providing secure communications for the Special Operations Command, South (SOCSOUTH), led by Colonel (COL) Robert C. ‘Jake’ Jacobelly.

Later, while he scanned his target from a cow pasture on the west side of the Pacora River, MAJ Higgins talked with Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) David J. Wilderman (J-3, SOCSOUTH) and Captain (CPT) Charles T. Cleveland (S-3, 3-7th SFG) “like they were standing next to me.”4 The SOCA team at Albrook provided Wilderman and Cleveland the situational awareness to prioritize high-demand assets, like the AC-130 Spectre gunship and the quick reaction force (QRF) at Albrook. Once committed, SOCSOUTH had nothing to reinforce other elements in contact.5 Clear and timely communications were essential to mission success on the opening night of Operation JUST CAUSE, and the 112th Signal Battalion SOCAs delivered. They continued to do so throughout the operation.

This article details 112th Signal Battalion origins and explains how it was manned and equipped as a dedicated special operations communications battalion. The battalion’s ‘trial-by-fire’ in Panama, 1989 – 1990 is highlighted. The focus is the SOCA teams that provided SOCSOUTH and ARSOF elements secure tactical communications during Operation JUST CAUSE and the follow-on stability operation, PROMOTE LIBERTY.

ORIGINS

The Army committed to modernizing its special operations forces (SOF) after the hostage rescue mission in Iran (Operation EAGLE CLAW) failed in 1980. 1st Special Operations Command (1st SOCOM) was provisionally established at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, in 1982, to command and control ARSOF. About the same time, forward-thinking officers began ‘beating the drum’ for a signal unit capable of supporting both 1st SOCOM and theater-level Joint Unconventional Warfare Task Forces (JUWTF).6

One such officer was MAJ James D. ‘Dave’ Bryan, a Special Forces (SF) and Ranger-qualified Signal Officer. His experience in 7th SFG (including two years commanding its signal company [1977 – 1979]) made him aware of the challenges inherent to joint special operations communications.7 When Bryan returned to Fort Bragg in June 1984 as the Assistant Chief of Staff/Communications and Electronics Officer, 1st SOCOM, he championed the creation of an ARSOF signal unit capable of supporting ARSOF headquarters and task forces in multiple theaters. At the time, neither the Joint Communications Support Element (JCSE), the only joint SOF signal unit, nor the SF signal companies, were resourced for those missions.8

Armed with Army studies and requirements documents, such as the Army Mission Area Analysis (1983), Special Operations Forces Master Plan (1984), and the Multi-command Required Operational Capability 2-84 (1984), Bryan prepared to brief his plan to the Army.9 He recognized that the Signal Corps would be reluctant to support the creation of a dedicated “ARSOF Communications Support Element,” which borrowed from Joint terminology; a signal battalion similar to those in the ‘Big Army’ would be an easier sell.10 Bryan identified three specific needs for an ARSOF communications battalion: a flexible structure that allowed SOF communications packages to be tailored to the supported mission; a modernization strategy that ensured ARSOF communicators had state-of-the-art equipment, through priority placement on the Department of the Army Master Priority List; and a “professional home for ARSOF communicators” that grounded them for continuity and did not stunt their career progression.11 His pitch succeeded, and the Army approved Table of Organization and Equipment (TO&E) 11015J500, “Special Operations Communications Battalion,” on 1 April 1985.

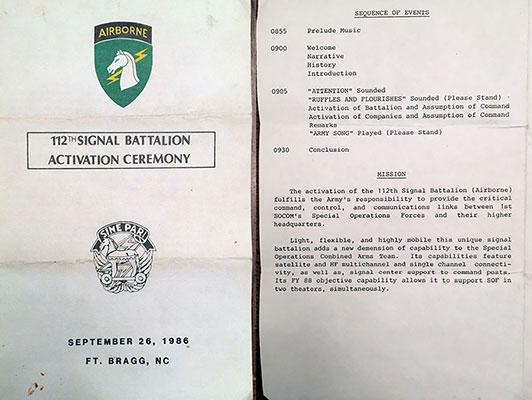

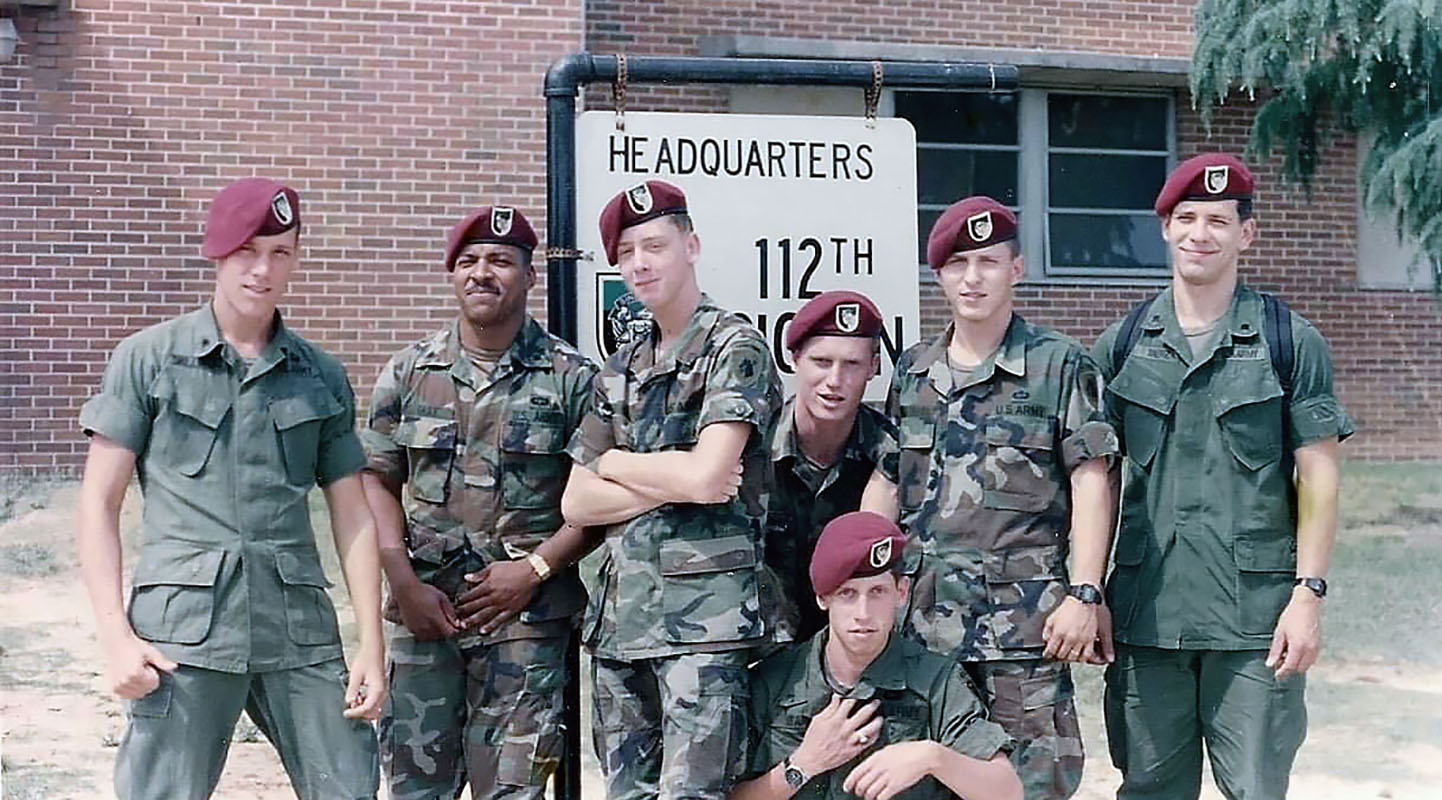

The 112th Signal Battalion (Special Operations) (Airborne) was established provisionally in June 1986, with Bryan in command, and was formally activated at Fort Bragg on 17 September 1986.12 It inherited the lineage of the World War II-era 512th Airborne Signal Company and the 112th Airborne Army Signal Battalion, both inactive since 1945. It had an authorized strength of 16 officers and 229 enlisted soldiers, organized into a Headquarters Detachment, a Base Operations Company and a Forward Communications Support Company.13 Manning came from excess Signal Corps billets rather than from within 1st SOCOM.14 Its soldiers quickly identified themselves as ‘Shadow Warriors,’ derived from the unit motto Penetra Le Tenebre – Penetrate the Shadows.15

Per the TO&E, the 112th Signal Battalion was to “provide required C3 [command, control, and communications] systems between the unified commander, major SOF headquarters, Army Special Operations Command [1st SOCOM] subordinate commands, and other commands as required/directed.”16 The battalion was to support SOCSOUTH and Special Operations Command, Europe (SOCEUR), which belonged to Army-supported combatant commands (COCOMs): U.S. Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM) and U.S. European Command (USEUCOM).17 The battalion was also “to establish communications liaison teams at various levels within the host country and/or supported and adjacent commands.” Those teams became synonymous with the equipment they used: the “Special Operations Liaison Communications Assemblage” (SOLCA), later simplified “SOCA.” The battalion’s fourteen SOCA teams were initially assigned to Company B, but a subsequent reorganization reallocated them evenly between two regionally aligned companies.18

Each SOCA team consisted of three soldiers: one Sergeant First Class (SFC/E-7), one Sergeant (SGT/E-5), and one Specialist (SPC/E-4), although it was not uncommon for Staff Sergeants (SSG/E-6) to serve as team leaders or for Privates First Class (PFC/E-3) to serve on SOCAs. Each team member was Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) 31C, Radio Operator-Maintainer or, less commonly, another 31-series MOS.19 Airborne-qualified and able to deploy on the first aircraft, SOCAs provided secure communications between the theater-level SOF commander and subordinate elements.20

Major General James David Bryan. In 2019, he was named an ARSOF Icon.

As the first 112th Signal Battalion Commander (‘Shadow Six’), LTC Bryan oversaw a period of rapid growth for the new battalion. It doubled in size, from 144 soldiers at activation to its full complement of 288 by mid-1988.21 Bryan prioritized getting the right people, fostering the right attitude, and providing them with the right equipment for the job.22 In this, he was aided by Command Sergeant Major (CSM) Billie F. Phipps, a capable battalion staff, and highly competent non-commissioned officers (NCOs). His command philosophy was condensed into five words: “Excellence in everything we do.”23

From the beginning, battalion leaders promoted a competitive mindset. The soldiers responded, believing that theirs was a special unit, due to its unique ARSOF support mission.24 Team sports and battalion runs built unit cohesion. Physical training was tough. Expectations were high, initiative was rewarded, and leaders were held accountable. Unit morale surged as a result.25 “They knew it was not ‘business as usual,’” Bryan recalled.26

Bryan also understood that most conventional Army communications systems were too bulky for ARSOF’s short notice, small footprint deployments. To get the right equipment, the battalion customized standard Army signal systems to meet mission requirements and procured cutting-edge commercial systems when necessary.27 It also fielded new super high frequency (SHF) satellite communications and high frequency (HF) multichannel systems. Special fabrication was done ‘in house,’ often with assistance from Tobyhanna Army Depot, Pennsylvania.28 Two such projects had major impacts.

The first was the SOCA kit, consisting of ultra-high frequency (UHF) tactical satellite (TACSAT), HF, and frequency modulation (FM) line-of-sight (LOS) radios; secure facsimile and teletype; encryption devices (KY-84, KY-57, KYV-5 or Sunburst processor); commercial power interface; and a generator.29 In its original configuration, the kit weighed over 1,200 pounds and was transported in a coffin-sized container.30 Battalion personnel cut the bulky metal racks that held the various systems to a more manageable size, and reorganized the other SOCA components until the entire kit fit in four footlocker-sized containers that could be carried by two soldiers and transported on a commercial aircraft.31 This was important because aircraft space dictated number of personnel and equipment size. The SOCA was often the only 112th communications package deployed on ARSOF missions.32

A second customization project was installing a dual rear axle on the standard five-quarter ton M-1028 Commercial Utility Cargo Vehicle (CUCV), making it capable of hauling an AN/TSC-93A multichannel satellite terminal previously transported by an M35 two-and-a-half ton truck.33 The eight-foot parabolic antenna, previously carried on a second truck, was modified to fit on a trailer attached to the custom CUCV.34 The entire system could roll on/off a C-130 or C-141 aircraft, something not possible in its original configuration, but essential for SOF employment.35

In June 1988, LTC Bryan handed over command of the 112th to LTC Steven R. Sawdey, a likeminded officer who Bryan first met in Korea in the early 1970s, when both were in the 2nd Infantry Division. The transition was nearly seamless, as Sawdey shared his predecessor’s commitment to technological innovation and realistic, mission-focused training.36 To him, getting the “right people” included airborne-qualified soldiers, and he fought to keep this requirement when manning shortfalls led the Army to send non-airborne personnel to the 112th.37 He also believed the best way to gain acceptance in the SOF community was to “get out there and do stuff.”38 Sawdey’s command philosophy reflected an aggressive mentality, and included an addenda: “Be prepared to kill for the mission.”39 CPT James S. ‘Steve’ Kestner, one of his company commanders, made sure that every one of his soldiers read it: “We were not your conventional signal unit.”40

The combination of tough training and high morale had LTC Sawdey’s ‘Shadow Warriors’ eager to deploy and prove themselves.41 Many of the battalion leaders, Kestner noted, were SF-qualified ‘long-tabbers’ or had previously served in Special Operations units, including its first two commanders.42 Senior NCOs were highly trusted, having been proven under stress.43 Experience had been gained in exercises like FUERZAS UNIDAS in USSOUTHCOM, and FLINTLOCK in USEUCOM. These exercises allowed the battalion to practice supporting a JSOTF, while identifying organizational and individual strengths and weaknesses.44

PANAMA

SOCAs gained operational experience in deployments to USSOUTHCOM, beginning with the HAT TRICK counterdrug missions in 1987.45 After COL Charles H. ‘Chuck’ Fry, the SOCSOUTH commander, requested SOCA support in early 1988, teams began 60 to 90-day rotations to Panama, Honduras, El Salvador, and Colombia, often with only a two week break between trips.46 The operational tempo (OPTEMPO) was grueling, but it became a point-of-pride for the SOCA men.47 Team leader SSG Thomas A. Ayers, a charter member of the battalion, recalls being gone so much during the late 1980s that his landlord prorated his rent, and joked that he needed a Green Card to get back into the country.48

The 112th’s SOCSOUTH mission took on greater importance as ARSOF intensified contingency planning for combat operations (BLUE SPOON) in Panama.49 MAJ Donald Kropp, battalion Operations Officer (S-3), represented the 112th Signal Battalion in those sessions, with First Lieutenant Oliver K. Wyrtki.50 Due to the persistent U.S. presence in Panama, robust fixed station communications networks already existed in the Canal Zone, but they were susceptible to attack from the Panama Defense Forces (PDF), and under surveillance by at least three Soviet ships transiting the Canal.51 Furthermore, existing secure military networks were insufficient to accommodate the demand resulting from the large influx of forces in BLUE SPOON. Accordingly, MAJ Kropp planned for the battalion to supply the Joint SOF headquarters in Panama with its own satellite communications network, but knew that it would take time to move the equipment into place.52

In early October 1989, with tensions between the U.S. and Panama escalating, two SOCA teams deployed as part of the security enhancement mission.53 Those teams, which included SSG McCrae and SGT Elizalde, were on the ground when Operation JUST CAUSE began on 20 December. However, the 112th did not receive the expected call to deploy more forces. As ARSOF units jumped into combat that night, and while 3-7th SFG carried out its D-Day missions, the majority of the 112th Signal Battalion was at Fort Bragg feeling “painfully invisible.”54

The omission was unintentional, a consequence of the short notice deployment, rapid pace of combat operations, and not being included early in the XVIII Airborne Corps-orchestrated deployment list. MAJ Kropp had planned a greater part for the 112th, but those factors reduced the battalion role.55 As a result, ‘Shadow Warrior’ contributions to JUST CAUSE were largely tactical. It was “SOCA-led war for the 112th,” said CPT Kestner. Regardless, LTC Sawdey sent him to Panama to “sort out what’s going on” and to figure out how to get more of the battalion into the fight.56

On 20 December, CPT Kestner and SFC Robert Malton flew to Panama, arriving at Howard Air Force Base. The two were taken by a 3-7th SFG security element to SOCSOUTH headquarters at Albrook Air Station. There, Kestner briefed COL Jacobelly, who praised the two SOCAs in country. He told Kestner to help the SOCSOUTH J-3 and J-6 ‘plus up’ signal support by writing a Statement of Requirements to justify more SOCAs.57 Kestner worked with MAJ Roberto A. Ortiz, the J-6, and CPT Charles Cleveland, the S-3, 3-7th SFG.

As CPT Kestner worked to get more SOCAs into Panama, Hangar 450 at Albrook came under fire a second time, most likely stray rounds from a gunfight near Quarry Heights.58 The SOCA radio operators noticed that the radio signal was suddenly much weaker. Quickly checking their equipment, they discovered that the tactical satellite antenna atop the hangar was rendered inoperable by gunfire.59 A backup system was activated, but it was a reminder that the fight was ongoing, despite major tactical successes in the opening days.

With the requirement for three additional SOCAs validated on 24 December 1989, the teams were notified.60 SSG Thomas Plunkett, SGT Darell A. Brown, and SPC Glenn G. Oliver made up one of those SOCAs. Like many, SGT Brown had been to Central America multiple times since joining the 112th two years prior. This time, inclement weather at Fort Bragg presented an unexpected obstacle to him and the others assembling for deployment. A neighbor with a four-wheel drive (4x4) vehicle delivered SGT Brown to his unit.61 LTC Sawdey sent out 4x4 trucks to gather others stranded by the snow.62 Once all of the teams were present, they departed as scheduled, reporting to SOCSOUTH Headquarters on Christmas Day.63

Initially, the SOCAs in country were all located near Panama City, either at Albrook or Howard, but several ‘pushed out’ with supported ARSOF elements.64 SGT Brown’s SOCA team stayed at Albrook, providing a link between SOCSOUTH HQ and the teams at the remote forward operating bases (FOBs). SSG Thomas A. Ayers’ SOCA team, by contrast, went to FOB 72 at Rio Hato airfield with Operational Detachment Bravo (ODB) 710, 2-7 SFG, who had relieved the Rangers. They kept information flowing between the Operational Detachments Alpha (ODAs) operating in the field and the ODB, and between the ODB and SOCSOUTH HQ.65