Fifty-five years ago, on 30-31 January 1968, the North Vietnamese Army, in conjunction with their Viet Cong allies, launched an ambitious country-wide offensive in South Vietnam. Hoping to break the will of the South Vietnamese military and stimulate a popular uprising against the pro-American South Vietnamese government, they committed more than 80,000 troops to the initial wave of attacks.1 Timed to begin during the Tet Mau Than holiday, which marked the start of the lunar new year, the offensive soon took on the abbreviated name of that holiday: Tet. Four Green Berets from the 5th Special Forces Group (Airborne) demonstrated exceptional valor during a five-week period in early 1968, immediately preceding and during the Tet Offensive.

U.S. Army Special Forces

and the Escalation in Vietnam

The U.S. Army’s advisory role in South Vietnam began in the late 1950s with the deployment of Mobile Training Teams, including some drawn from the Army’s nascent Special Forces units. The advisory mission accelerated in the early 1960s due to U.S. President John F. Kennedy’s preferred counterinsurgency strategy, which leaned heavily on Army Special Warfare, particularly Special Forces. This strategy emphasized building the capacity of South Vietnam’s Armed Forces and other indigenous partners, securing the populace, and defeating the Viet Cong, the main Communist insurgent force. Special Forces was tailor-made for such missions.

In early 1965, the U.S. deployed its first conventional combat troops to Vietnam. Rather than advising, their mission was to decisively engage and defeat both the Viet Cong and the NVA operating in South Vietnam. Special Forces continued to play an important role and, although their numbers continued to grow, their overall share of the war effort decreased as conventional troop levels rose dramatically between 1965 and 1968.

More boots on the ground, coupled with more aggressive tactics, brought an increase in U.S. casualties. Still, General William C. Westmoreland, the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam commander, entered 1968 hopeful about the progress of the war. President Lyndon B. Johnson shared Westmoreland’s optimism. Both men anticipated a successful conclusion to the war, despite increased casualties and a burgeoning anti-war movement at home.

The North Vietnamese were also optimistic, believing that their planned offensive would turn the tide of the war decisively in their favor. Throughout January 1968, the NVA and Viet Cong maneuvered into their positions. To distract U.S. and South Vietnamese forces, the Communists conducted diversionary attacks in the weeks leading up to the Tet holiday. One such attack took place east of the village of Thong Binh, South Vietnam, on 16 January 1968.

SGT Gordon D. Yntema

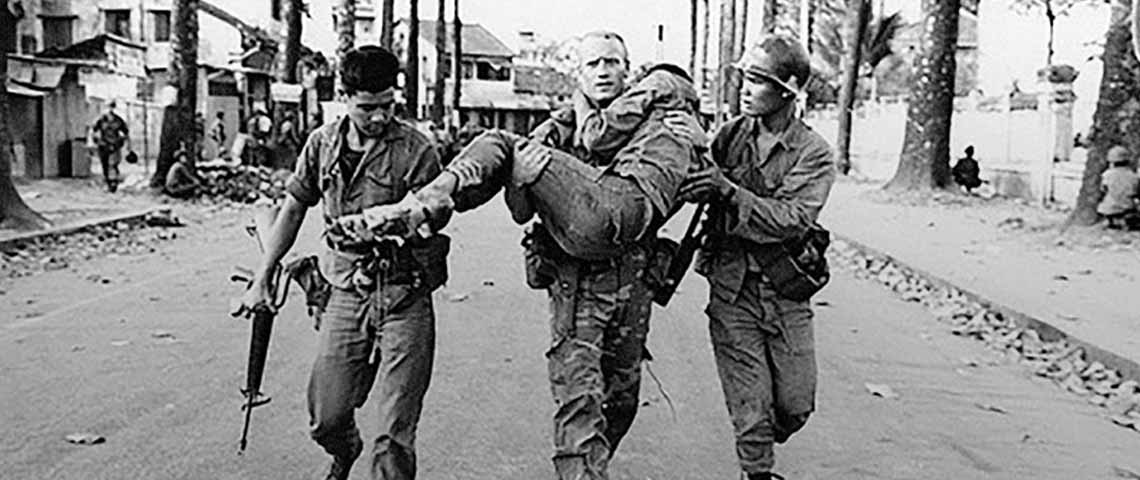

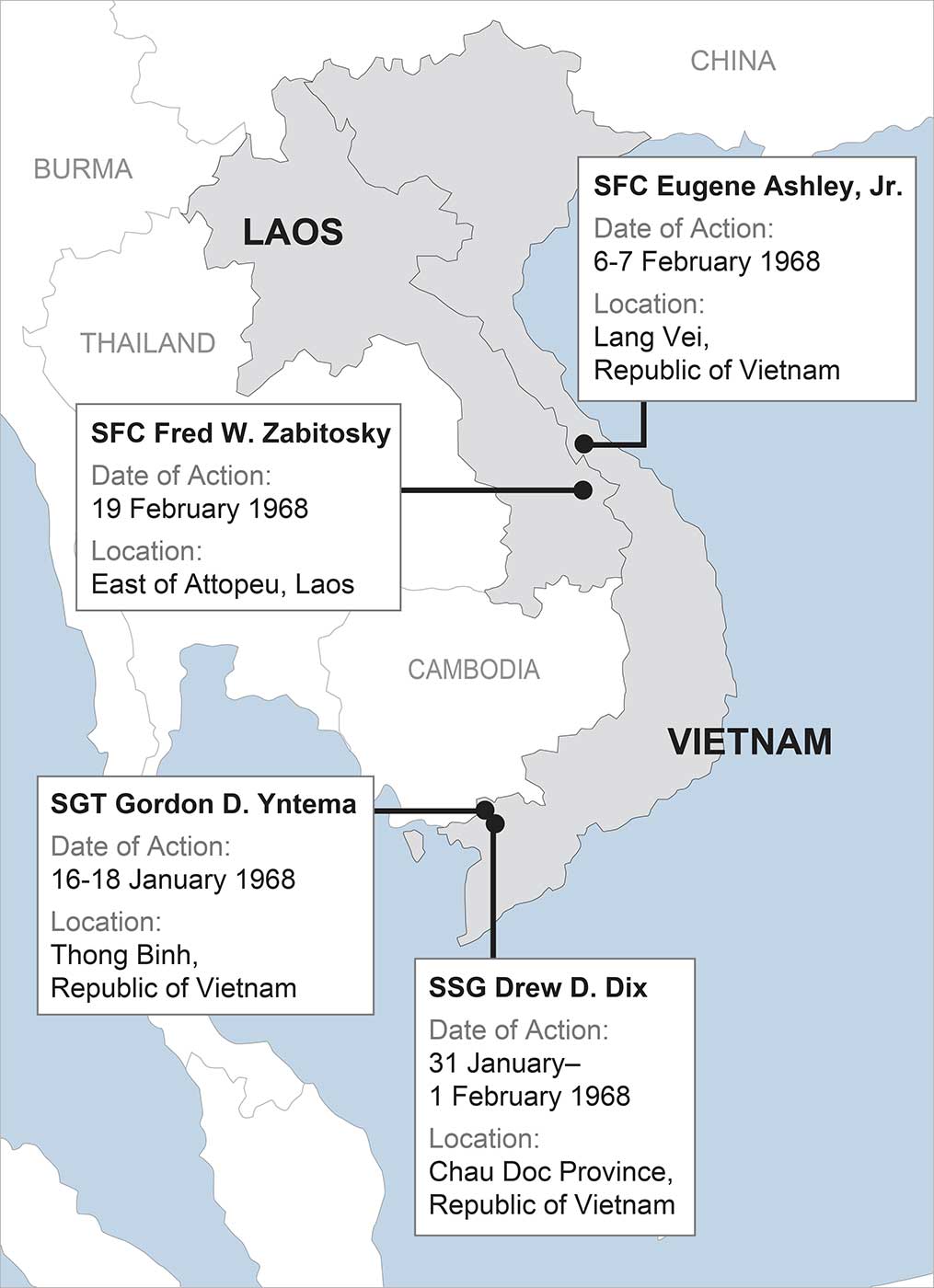

During the ensuing battle, SGT Gordon D. Yntema accompanied two platoons of civilian irregulars to a blocking position east of the village of Thong Binh, where they were attacked by a much larger force of Viet Cong. Yntema assumed control of the element after its commander was seriously wounded and led a tenacious defense despite overwhelming odds. Out of ammunition and reduced to using his rifle as a club, he held his ground until succumbing to enemy fire.2

SSG Drew D. Dix

Two weeks later, on the morning of 30 January 1968, communist forces attacked eight major South Vietnamese cities. The next day, fighting erupted almost everywhere across South Vietnam as the communists attacked more than 60 towns, 36 provincial capitals, and five of South Vietnam’s autonomous cities, including the capital city, Saigon.3 Chau City, capital of Chau Doc Province, was attacked by two Viet Cong battalions. SSG Drew D. Dix, along with the South Vietnamese patrol he was advising, were called on to assist in the defense of beleaguered city.

SSG Dix organized and led two separate relief forces that successfully rescued a total of nine trapped civilians. He subsequently assaulted an enemy-held building, killing six Viet Cong and rescuing two Filipinos. The following day, he assembled a 20-man force and cleared the Viet Cong out of a hotel, theater, and other adjacent buildings within the city. In the process, he captured 20 prisoners, including a high-ranking Viet Cong official. He then cleared enemy troops from the Deputy Province Chief’s residence, rescuing that official’s wife and children in the process.4

SFC Eugene Ashley, Jr.

A week later, on the evening of 6 February 1968, the NVA launched a surprise attack on the Special Forces camp at Lang Vei, in the northwest corner of South Vietnam. With the camp’s surviving Special Forces advisors trapped in a bunker, SFC Eugene Ashley, Jr., organized a rescue effort, consisting mainly of friendly Laotians.

SFC Ashley led his ad hoc assault force on a total of five assaults against the enemy, continuously exposing himself to withering small arms fire, which left him seriously wounded. During his fifth and final assault, he adjusted airstrikes nearly on top of his assault element, forcing the enemy to withdraw and resulting in friendly control of the summit of the hill. Following this assault, he lost consciousness and was carried from the summit by his comrades, only to suffer a fatal wound from an enemy artillery round. Ashley’s valiant efforts, at the cost of his own life, made it possible for the survivors of Camp Lang Vei to eventually escape to freedom.5

SSG Fred W. Zabitosky

Later that month, on 19 February 1968, SSG Fred W. Zabitosky was part of a nine-man Special Forces long-range reconnaissance patrol operating deep within enemy controlled territory in Laos when his team was attacked by a numerically superior NVA force. Zabitosky rallied his team members and deployed them into defensive positions. When that position became untenable, he called for helicopter extraction. He organized a defensive perimeter and directed fire until the rescue helicopters arrived. He then continued to engage the enemy from the helicopter’s door as it took off, but the aircraft was soon disabled by enemy fire.

SSG Zabitosky was thrown from the helicopter as it spun out of control and crashed. Recovering consciousness, he moved to the flaming wreckage and rescued the severely wounded pilot. Despite his own serious burns and crushed ribs, he carried and dragged the unconscious pilot through a curtain of enemy fire before collapsing within ten feet of a hovering rescue helicopter. Zabitosky would become the fourth Green Beret to receive the Medal of Honor for actions during the Tet Offensive period, joining Yntema, Dix, and Ashley.6

These four Special Forces heroes were in good company. The mettle of the U.S. forces in Vietnam was severely tested during the opening months of 1968 in places such as Hue, Saigon, Lang Vei, Dak To, Quang Tri, and Khe Sahn. At every turn, the men and women of the U.S. military rose to the occasion, demonstrating indomitable valor and dealing the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong a crushing defeat. Combined, the Communist forces lost an estimated 72,455 soldiers between January and March 1968, compared with 15,715 allied dead, of which 4,869 were Americans.7

A Turning Point:

The Impact of the Tet Offensive

The ferocity of the Tet Offensive, and the resulting increase in U.S. casualties, alarmed both U.S. government officials and the American people. It also discredited the claims of progress from both military and political leadership.8 Anti-war protests intensified as more and more Americans came to share the assessment of popular news anchor Walter Cronkite that the war in Vietnam was unwinnable. President Johnson terminated his reelection campaign. The fighting continued under his successor, Richard M. Nixon, who adopted a strategy of “Vietnamization,” characterized by a gradual transfer of responsibility to South Vietnamese forces and a phased drawdown of U.S. troops.

On 27 January 1973, nearly five years to the day after the start of the Tet Offensive, the United States, North Vietnam, South Vietnam, and the Viet Cong signed the Paris Peace Accords. The long U.S. combat mission in Vietnam ended two months later, on 29 March 1973. North Vietnam later resumed offensive operations, eventually capturing Saigon on 30 April 1975, thereby ending the war and uniting Vietnam under Communist rule.

As of publication, twenty-three Green Berets earned the nation’s highest award for valor for service in Vietnam, eight of them posthumously. In the 50 years since, time has not dimmed, nor will it ever dim, the glory of their deeds. Their valorous actions, often at the cost of their own lives, continue to inspire U.S. Army Special Operations Forces soldiers, the U.S. Army, and the nation.