DOWNLOAD

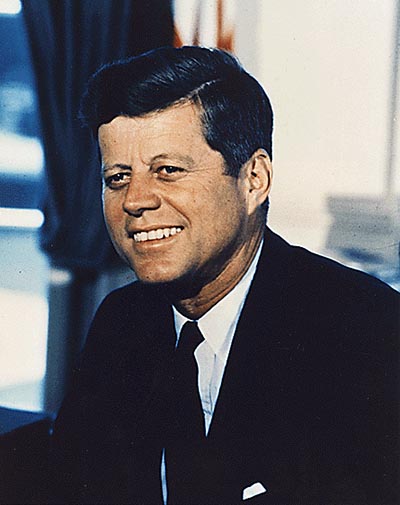

President John F. Kennedy (JFK) was a staunch advocate of U.S. Army Special Warfare, as highlighted in previous articles about his 12 October 1961 visit to Fort Bragg, North Carolina and his remarks to the U.S. Military Academy’s graduating class on 6 June 1962. He viewed Special Forces (SF) in particular as being a critical component of his “flexible response” strategy to address the challenges of Communist-inspired “wars of national liberation.” In April 1962, the President famously described the green beret as “a symbol of excellence, a badge of courage, a mark of distinction on the fight for freedom.”1 The name of JFK thenceforth became irrevocably linked with Special Forces.

Unfortunately, Kennedy’s life was tragically cut short by his assassination in Dallas, Texas, on 22 November 1963. The President’s widow, Jacqueline Kennedy, and brother, U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, insisted on an SF presence at his memorial services in the ensuing days. The 60th anniversary of Kennedy’s death inspired this article detailing how SF soldiers honored their fallen commander-in-chief, initiating a longstanding tradition of memorialization. What follows is a daily recounting of events in late November 1963 as they unfolded. It will then summarize the many ways in which Army Special Forces have honored JFK in the decades since.

Friday, 22 November 1963

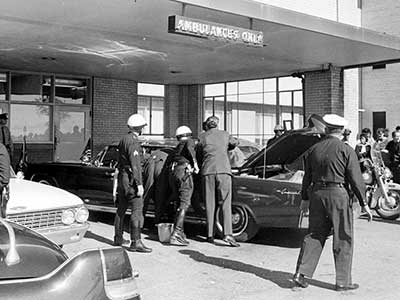

Having arrived at nearby Love Field in Dallas aboard Air Force One an hour earlier, the President and Texas Governor John Connally were shot while riding in an open limousine in Dealey Plaza at 1230 hours local time. Kennedy was driven immediately about four miles away to Parkland Memorial Hospital for lifesaving aid. While Connally would survive, Kennedy’s wounds were too severe, and he was pronounced deceased at 1300 hours (the formal White House announcement being made about 35 minutes later). Shortly thereafter, CBS news anchor Walter Cronkite famously became emotional as he informed the nation of JFK’s passing.2

Kennedy’s body was transported to Love Field and placed on Air Force One. Onboard, Vice-President Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ) took the oath of office from U.S. District Court Judge Sarah Hughes at 1438 hours. The plane soon began a roughly three-hour flight to the capital, arriving at Andrews Air Force Base, Maryland, around 1900 hours local. Kennedy was transported to Bethesda Naval Hospital, where an autopsy was conducted overnight.3

Saturday, 23 November 1963

Around 0400 hours on Saturday, JFK’s casket arrived at the White House and was greeted by a U.S. Marine Corps Honor Guard. It was then transported into the East Room by a six-man joint casket team. A private religious ceremony was held in the East Room at 1000 hours.4 An hour later, the U.S. Army Special Warfare Center and School (SWCS) at Fort Bragg received notification of Mrs. Kennedy’s and Attorney General Kennedy’s desire for an SF contingent in Washington. The Center scurried to publish and distribute temporary duty orders for 46 soldiers from 5th SF Group (SFG), 6th SFG, 7th SFG, and HQ, SWCS. The largest group (21) came from 7th SFG (mostly from Company C), followed by 5th SFG with fourteen, 6th SFG with eight, and HQ, SWCS with three. Ranks ranged from private first class (PFC) to colonel (COL), with the most represented rank (13) being sergeant first class (SFC). The head of the contingent was Deputy Commanding Officer, SWCS, Colonel (COL) William P. Grieves, accompanied by the SWCS Sergeant Major (SGM), Francis J. Ruddy.5

Moving out on extremely short notice, the contingent left by air from Pope Air Force Base, arriving in Washington at around 1600 hours. Upon arrival, three SF soldiers immediately reported to the White House and stood by the casket in the East Room. For the remainder of the memorial activities, at least one SF soldier accompanied the slain President around the clock. According to a Veritas article at the time, “Because of the hurried manner in which they were rushed to the capital, the Special Forces soldiers had little time to practice and many of their actions were without rehearsal.”6 Their prompt and dedicated support were indicative of the adaptive spirit of Army Special Forces that had been so prized by the former President.

Sunday, 24 November 1963

At 1308 hours on Sunday, a caisson bearing the President’s coffin, drawn by six grey horses and followed by one riderless black horse, departed the White House for the U.S. Capitol. Special Forces soldiers were among those in the two-mile procession, with mourning crowds lining both sides of Pennsylvania Avenue. One of the four SF escorts, SFC Robert C. Rumrill, Company C, 7th SFG, later remarked, “It is the greatest honor I have ever had as an individual … There could be no greater honor, especially for the professional soldier, than to serve at such a time. I was very proud to be on [the SF escort detail].”7”

Forty minutes later, the President’s casket had arrived at the Capitol and was placed on a platform in the Rotunda that had been constructed to hold President Abraham Lincoln’s casket nearly one hundred years prior. There, he would lay in state for the next 18 hours, to be visited by roughly a quarter million people, some of them waiting for up to twelve hours. Master Sergeant (MSG) William E. Heintzleman, Company C, 7th SFG, “couldn”t believe that so many people would stay out all night in the cold without being compelled to pay their respects … It was very impressive.”8

At 2100 hours, MSG Thomas F. Gaffney, Company B, 7th SFG, arrived with and assumed command of the SF relief element in the Rotunda. During their watch, the former First Lady made an unexpected visit to the casket.9 “She came with Robert Kennedy,” Gaffney recalled, “approached the casket, crossed herself, knelt and kissed the coffin.”10 Staff Sergeant (SSG) William H. Fuller, Company D, 5th SFG, was one of the SF team members on duty in the Capitol, and recalled the presence of such notables as Chief Justice Earl Warren, Senate Majority Leader Michael J. Mansfield, and Speaker of the House John W. McCormack who, like the general public, were visibly grieved. Fuller noted how so many people “looked as though he (the President) was a personal friend; as though they had lost someone in the family.”11

Monday, 25 November 1963

The 25th of November marked the culmination of memorialization activities for the fallen President. At 0900, the doors to the Capitol Rotunda were closed to the public. The caisson left Capitol Hill nearly two hours later at 1059 hours. Pausing briefly at the White House, the caisson and procession, among them marching SF soldiers, moved to St. Matthew’s Cathedral at 1140 hours. At about a quarter after noon, the President’s coffin entered St. Matthew’s Cathedral for a religious service, which was attended by more than a thousand people representing nearly 100 countries.12

At 1330 hours, the funeral procession began making the roughly three-mile trek to Arlington National Cemetery, with an estimated million people lining the route. Several SF soldiers noted the overwhelmingly somber mood of the occasion. According to Specialist 4th Class George M. Thompson, Company A, 6th SFG, “We had gone about halfway along the route … when suddenly I realized that all you could hear was the sound of the drums. Nobody was talking, just some people crying.”13 One sergeant from 7th SFG recounted how some of his friends who had seen him in the procession on television had accused him of chewing gum. In reality, “I was having great difficulty keeping my face straight and restraining my emotions. A number of big, tough, airborne soldiers were having the same problem.”14

Upon arrival of the procession at Arlington shortly before 1500 hours, the National Anthem was played, followed by a marching U.S. Air Force (USAF) bagpipe troupe. As they played, eight military pallbearers removed the casket from the caisson and made their way to the gravesite, with SF soldiers lining the pathway. According to Major James C. Hefti, Company A, 7th SFG, responsibility for this cordon would have normally fallen to a joint service detail, but Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara directed that it be solely SF soldiers. One of those along the walkway, SFC Robert G. Daniel, Company C, 7th SFG, recalled Prince Philip of the United Kingdom conducting impromptu inspections as he passed by the SF soldiers, “paying close attention to their medals and ribbons.”15

At 1454 hours, just as the casket arrived at the gravesite, fifty fighter aircraft (thirty F-105 Thunderchiefs from the USAF 4th Tactical Fighter Wing and twenty Navy F-4B Phantoms), followed by Air Force One, conducted a flyover.16 The service continued as the casket team held the flag taut over the coffin. Among the dignitaries graveside were Kennedy’s immediate family, President Johnson, French President Charles de Gaulle, Emperor of Ethiopia Haile Selassie, and the West German President and Chancellor, Heinrich Lübke and Ludwig Erhard, respectively. SF soldiers maintained their bearing and composure during their solemn duties but passively observed the demeanor of those around them. SFC Daniel viewed Johnson as “well in command. He had a good bearing and showed great authority.” He also noted that De Gaulle “demanded respect” just by his general appearance.17

Interspersed with the ensuing religious proceedings were a 21-gun salute and three rifle volleys. Taps was played at 1507 hours, followed by the folding of the flag. At 1515 hours, Jacqueline Kennedy, accompanied by Robert and Edward (‘Ted’) Kennedy, lit the eternal flame.18 The lighting of the eternal flame essentially concluded the graveside service, with the departure of the official party soon after. Following the services, with four SF soldiers standing guard, SWCS SGM Francis J. Ruddy placed a green beret, crest forward, at the foot of JFK’s grave. In words that have since become immortalized, Ruddy explained, “He gave the beret to us and we considered it appropriate that it be given back to him. It was a final memorial from the Special Forces to the President.”19 This beret is today held by the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston, Massachusetts.”

By the end of Monday, 25 November 1963, the 46 members of the SF group were back at Fort Bragg. The team had felt a tremendous sense of pride in having been selected for the honor of participating in this solemn event. However, they likely agreed with the sentiments of SSG Ronald P. Morris, Company E, 7th SFG, who said, “I hope to God that it never happens again.”20 Thankfully, Morris’s fears have not been realized, though an attempt was made against President Ronald Reagan’s life seventeen years later on 30 March 1981.