NOTE

* Pseudonym

DOWNLOAD

The year 2023 marks thirty years since the Battle of Mogadishu in Somalia on 3-4 October 1993. The mission objective was for Task Force Ranger—which included soldiers from the 75th Ranger Regiment, the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (SOAR), and other Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF) units—to capture high-value associates of Mohamed Farrah Aidid, head of the Somalia National Alliance (SNA). Aidid, a powerful warlord aspiring to be president, had been frustrating United Nations Operations in Somalia II (UNOSOM II) efforts to bring relief to the starving and war-torn country, to include killing UN peacekeepers. The U.S. believed it was time to bring Aidid to justice.

Task Force Ranger had already made six attempts to track down Aidid since its arrival in August 1993, capturing members of his inner circle along the way. Intended to last less than an hour, the mission on 3 October devolved into some of the fiercest urban combat since Vietnam, becoming an overnight fight for survival and exfiltration in the face of thousands of SNA and irregular fighters. With the support of conventional, joint, and international partners, ARSOF soldiers achieved their tactical objectives, but at the cost of eighteen lives lost, dozens more wounded, and two downed MH-60 Black Hawk helicopters.1

ARSOF soldiers earned recognition for their heroism and sacrifice during the battle, among them Master Sergeant (MSG) Gary I. Gordon and Sergeant First Class (SFC) Randall D. Shughart, who posthumously received the Medal of Honor.2 However, the political fallout from the Battle of Mogadishu led to the withdrawal of all U.S. forces from Somalia within six months, followed by the end of UNOSOM II in March 1995. Public perception of the battle was initially shaped by media coverage, as it would take time for the Department of Defense (DoD) to research and publish detailed historical accounts on U.S. military operations in Somalia.3 In the meantime, the mission came into sharper view in the public eye through the book Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War (1999) by journalist Mark Bowden, and the film that it inspired, Black Hawk Down (2001), produced by Jerry Bruckheimer and directed by Ridley Scott.

Starting in late 2000, DoD public affairs elements helped coordinate ARSOF support to the film’s writers, producers, and actors. From the outset, the U.S. Army Special Operations Command (USASOC) sought to ensure that the battle and those who fought and died in it were appropriately represented and received a fitting tribute. This collaboration contributed to the film’s harsh depictions of modern combat and its gritty yet inspiring tone. As a result, the award-winning Black Hawk Down helped shape popular understanding about this significant event. After providing a brief chronology of the film’s development and release, this article describes how USASOC assisted the production of Black Hawk Down.

The time between the publication of Bowden’s book and the national release of the film Black Hawk Down in January 2002 was less than three years. Ken Nolan was the only credited screenwriter, though he was assisted by Bowden and others with the ever-evolving script. Filming took place primarily in and around Rabat, Morocco, between March and June 2001. In late May 2001, the film’s first trailers accompanied the release of Pearl Harbor (which also featured Josh Hartnett, who played Staff Sergeant Matthew Eversmann in Black Hawk Down). The film’s tentative release date was 2 November 2001, but the deadly 9/11 terrorist attacks on the U.S. led filmmakers to briefly reconsider delaying it until spring 2002. As one news source at the time reported, “Just six weeks ago, as the events of Sept. 11 shook America, Hollywood rushed to postpone any terror-related films that might offend public sensibilities, abruptly pulling a number of completed pictures … because of fears that Americans wouldn’t want to see war movies any time soon.”4 However, by November, “those concerns appear[ed] to be receding,” and Hollywood decided to start releasing Black Hawk Down in late 2001.5

The premiere of Black Hawk Down occurred on 18 December, followed by limited release in Los Angeles and New York City ten days later. Distributed by Sony, it hit theaters nationwide on 18 January 2002, eventually grossing roughly $173 million worldwide against a $92 million budget. Nominated for numerous awards, Black Hawk Down won the categories Best Film Editing and Best Sound at the 74th Academy Awards in March 2002.6 Less well known was how much support the acclaimed film had received from USASOC, headquartered at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, prior to and during production. This relationship all started with a phone call from the Pentagon to Fort Bragg in late 2000.

Special Forces (SF) Major (MAJ) Timothy McAllister* was serving in the U.S. Army Special Forces Command (USASFC) G-3 at Fort Bragg when he was contacted by Philip M. Strub, DoD Film/Entertainment Coordinator in the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, about the proposed film. Strub considered McAllister* an ideal DoD project officer due to his ARSOF affiliation and his previous assignment as an entertainment liaison in the U.S. Army Public Affairs Office (PAO) in Los Angeles, California. The Commanding General (CG) of USASFC, Brigadier General (BG) Frank J. Toney, Jr., approved McAllister’s* participation in a preliminary meeting with Strub and Bruckheimer in the Pentagon. At the meeting, Bruckheimer pitched the concept for Black Hawk Down, with assurances that “every soldier would come out as a hero,” and requested DoD technical and materiel support to the film at the producer’s expense.7

As the higher command for all ARSOF units, USASOC emerged as the most obvious Army command to provide this requested support. Upon returning to Fort Bragg, McAllister* relayed Bruckheimer’s request to the CG, USASOC, Lieutenant General (LTG) Bryan D. Brown. With the DoD already on board, Brown enthusiastically pledged full support to the producers.8 Over the next several months, USASOC support took three main forms: review of Nolan’s draft script; providing ARSOF familiarization and training to the actors; and soldiers, technical expertise, and equipment during the filming itself in Morocco. The pace moved quickly due to the short amount of time between the request for support and the designated time for filming.

USASOC received the draft script in early December 2000, which was in turn provided to the 75th Ranger Regiment and 160th SOAR (“Night Stalkers”), to be returned with comments no later than 11 December. While realizing that the filmmakers would take creative license, the 75th and 160th went through great pains to guarantee that their units, soldiers, and fallen heroes were as truthfully represented as possible. They strove for realism and accuracy, to include ensuring that the characters talked, looked, and acted like real ARSOF soldiers. The producers accepted many but not all of their recommended changes; due to the number of deviations, they elected to change the first line of the film from “This is a true story” to “Based on an actual event.” ARSOF units continued to review revised scripts, even during filming in Morocco.9 Meanwhile, in early 2001, arrangements were made for actors to receive familiarization with and training from 7th Special Forces Group (SFG) at Fort Bragg, the 160th SOAR at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, and the 75th Ranger Regiment at Fort Benning, Georgia (known as Fort Moore since 2023).

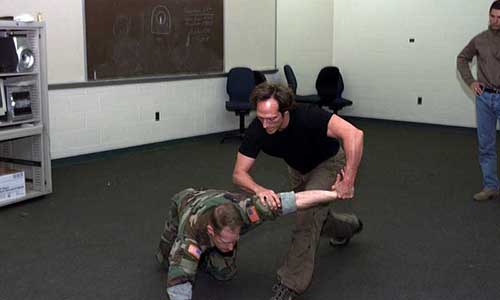

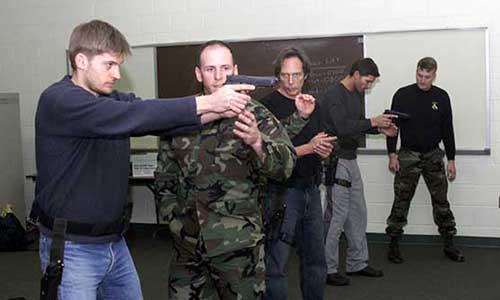

Those visiting 7th SFG included actors William Fichtner and Eric Bana, who portrayed fictional composite characters SFC Jeff Sanderson and SFC Norm ‘Hoot’ Gibson, and Nikolaj Coster-Waldau, who portrayed Medal of Honor recipient MSG Gary I. Gordon. Training received from SF soldiers included weapons familiarization, Military Operations on Urbanized Terrain (MOUT), explosive breaching, close-quarters combat, hand-to-hand fighting, and Fast-Rope Insertion and Extraction System (FRIES) orientation. According to Fichtner, “Before reading the script, all I knew about what happened in Somalia was from CNN sound bites—that we had gone in there to help feed the starving people there and then something went wrong so we left.” His experience at Fort Bragg was eye-opening and memorable. “In preparing for my role, I made a number of real friends in the Army down [at] Fort Bragg, not just acquaintances but friends. I am proud of what my new friends do on a daily basis in defending this country.”10

Meanwhile, actors Jeremy Piven and Ron Eldard, who played Clifton P. Wolcott and Michael J. Durant, pilots of the two downed MH-60s, visited their 160th SOAR counterparts at Fort Campbell. This included familiarization with special operations helicopters, equipment, and capabilities; meetings with veterans from Somalia, to include receiving a briefing on the battle from Durant himself; and paying respects at the Night Stalker memorial wall outside of the regimental headquarters. In addition, Eldard participated in a portion of Green Platoon, a stressful, physically and mentally intense training program that all incoming Night Stalker candidates must complete before joining the Regiment. While neither Eldard nor Piven flew any helicopters for the film, their experience at Fort Campbell helped familiarize them with Night Stalker culture and gave them a deeper appreciation for the 160th’s role in Somalia.

The largest group of actors to receive training was the nearly twenty individuals who visited the 75th Ranger Regiment at Fort Benning. Among these were Hartnett, Ewan MacGregor (who played Specialist [SPC] John Grimes), Orlando Bloom (who portrayed Private First Class Todd Blackburn), Tom Hardy (who played SPC Lance Twombly), Ewen Bremner (who played SPC Shawn Nelson), Jason Isaacs (who portrayed Captain Michael Steele, Commander, Company B, 3/75th Ranger Regiment [B/3/75]), and Tom Sizemore (who portrayed Lieutenant Colonel Danny R. McKnight, Commander, 3/75th Ranger Regiment). Given fresh “high and tight” haircuts, the actors received intensive training from roughly ten Rangers in weapons, MOUT, tactical drills, hand-to-hand fighting, first aid, signal, and helicopter familiarization. This crash course in Ranger culture and tactics were designed to help prepare the actors for the upcoming filming in Morocco. They would be joined in-country by actual ARSOF soldiers and equipment.