ABSTRACT

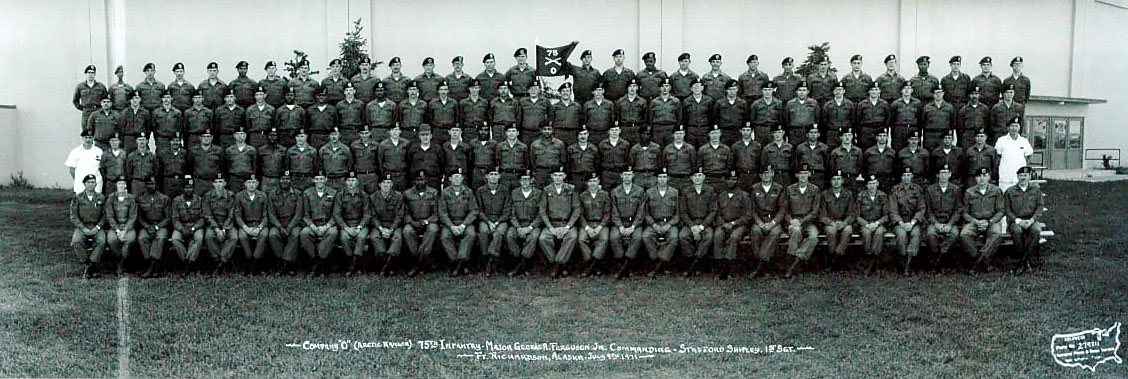

Between August 1970 and September 1972, a single U.S. Army Ranger Company that specialized in arctic reconnaissance was formed at Fort Richardson, Alaska. Little has been written about Company O, 75th Infantry (Ranger) Regiment. What is known is that while protecting early Alaskan oil infrastructure and performing search and recovery missions of lost personnel and aircraft, the “Arctic Rangers” tested the limits of both personal endurance and equipment in the most extreme arctic conditions. These men – an estimated 336 in all – held true to the Ranger tradition of leading the way for future generations.

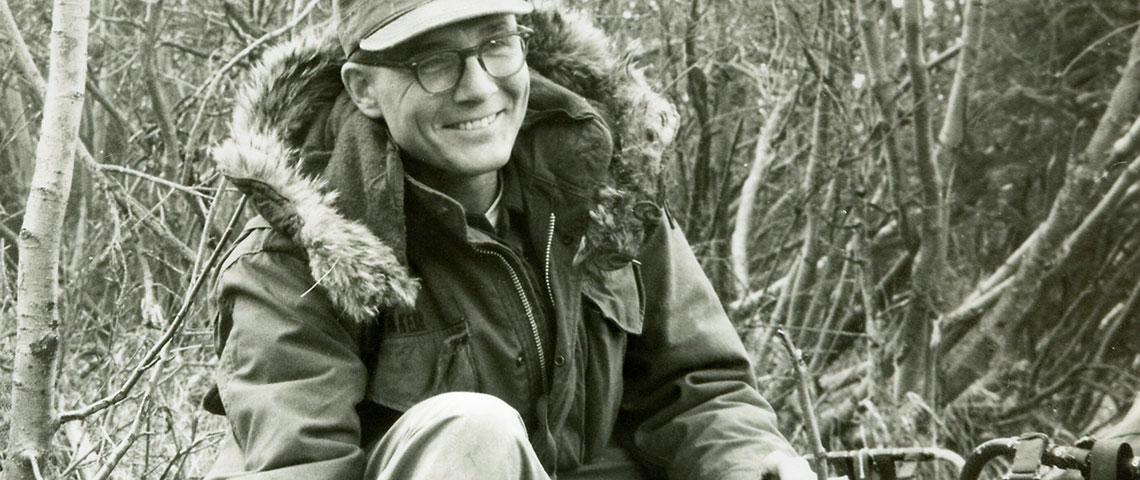

After his third tour in Vietnam, by 1970 Major (MAJ) George A. Ferguson was eager for a change of scenery. Alaska seemed the perfect contrast to the jungles he had traversed with units such as the 7th Special Forces Group. But, a month into his assignment at Fort Greely, Alaska, he faced one of the most unique challenges of his career – all due to a chance encounter with a charismatic former commander. At the direction of Major General (MG) James F. Hollingsworth, Ferguson embarked on a mission to stand up a new specialized unit under U.S. Army, Alaska (USARAL) .1 This article highlights the history of Company O, 75th Infantry (Ranger) Regiment, also known as the Arctic Rangers. This obscure special operations unit operated from 4 August 1970 to 29 September 1972 at Fort Richardson, Alaska, at a time when most Infantry Ranger companies were slowly deactivating after their return from Vietnam. While the Arctic Rangers only existed for two years, their tenacity and ingenuity left a lasting impact.

An Early Arctic Proponent

As early as 1960, Army leaders recognized the need for a specialized force capable of operating in the arctic. While G-3 at USARAL, Colonel (COL) Willard Pearson contributed to a presentation with this theme for the 1960 Quartermaster Conference, highlighting Alaska’s strategic importance.2 Pearson understood the Soviet threat from the west and wanted to make sure the U.S. could defend its arctic border. He republished this presentation again in 1961 for a broader audience in Military Review under the title, “Alaska: Gibraltar of the North.” In it, he appealed to Army leaders to act swiftly lest the nation face serious consequences:

Should an enemy secure even a limited beachhead on the bleakest coast of northern Alaska, he could proclaim to the world that U.S. territory had been successfully invaded. Invasion of U.S. soil would adversely influence the uncommitted nations in the early stages of a general war. An invader would gain great psychological and propaganda value from even nuisance raids on U.S. soil.3

He went on to recall the “panic and hysteria” following the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 and noted the Soviet Union’s proximity as a viable threat, with only 55 miles of water separating it from Alaska. In the Bering Strait, the U.S. Little Diomede Island was just three miles from Russia’s Big Diomede Island.4 Soviet advances in military readiness had also been top of U.S. leaders’ minds since the beginning of the Cold War.5 Pearson, who later rose to the rank of lieutenant general, wrote frequently throughout the 1960s about the need for the Army to begin taking the Soviet threat along the Alaskan coast seriously and continued to press for leveraging Alaska as an optimal arctic training ground. He noted, “A realistic program started now would ensure the Army’s readiness to fight in this strategic northern area.”6

Pearson knew that the Army’s arctic training for soldiers was limited. Not until 1948 did the Army establish the Army Arctic School at Big Delta, Alaska, later named Fort Greely. The school had taught individuals arctic and subarctic survival skills. Fort Greely assumed full responsibility for individual cold weather training in 1957 as the U.S. Army Cold Weather and Mountain School. In 1963, it implemented unit training as it transitioned to the Northern Warfare Training Center.7

In 1968, then-Major General Pearson, the Army’s Director of Individual Training, wrote a confidential proposal to the Assistant Chief of Staff for Force Development. Pearson presented “several ideas on improving efficiency of units in Alaska,” while leveraging the environment for arctic training.8 The proposal suggested that the commander of USARAL have the latitude to build a specialized capability adapted to arctic conditions.9

Meanwhile, the future of Ranger companies, initially formed for use as Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol (LRRP) units in Vietnam, was also an issue for Army leaders. As American involvement in Vietnam wound down, these leaders discussed whether Rangers were still needed and, if so, how to employ them effectively and efficiently in future operations.

Under the Combat Arms Regimental System, fifteen Ranger companies had been activated under the 75th Infantry Regiment in 1969, thirteen of which operated in Vietnam. Company O was activated on 1 February 1969, and attached to the 3rd Brigade, 82nd Airborne Division, at Fort Bragg, but was inactivated less than 10 months later on 20 November.10

However, after more than a decade of Pearson’s advocacy and ongoing senior leader discussions about the future of the Ranger companies, MG Hollingsworth, commander of USARAL and a highly decorated Vietnam veteran, was keen on leveraging the expertise of the LRRPs.11 Who would lead it was a mystery, until that chance encounter between Hollingsworth and MAJ George Ferguson in mid-1970. On 4 August 1970, Company O was reactivated at Fort Richardson, Alaska.12

Ferguson recalls that his assignment came down to being in the right place at the right time. He had previously worked for Hollingsworth at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, and had briefed him regularly. “I asked to be sent to Alaska,” Ferguson said. “I was tired of jungle operations.” An Infantry Officer, he was assigned as an Operations Officer at Fort Greely, Alaska, for about a month when Hollingsworth took over as commander of USARAL in July 1970. As Hollingsworth was touring the state to meet his troops, Ferguson was once again in the role of briefer at Fort Greely. “After the briefing, he called me in and said, ‘Major Ferguson, would you like to be the Ranger company commander for the northern area?’ I said, ‘Sir, I’m not Ranger qualified.’ He said, ‘I didn’t ask you that, I asked if you wanted to be the commander.’ I said, ‘Yes, sir.’”13

Ferguson was not quite sure what he was getting into. With just a week to move his family about three hundred miles to Fort Richardson, the next two months were very chaotic as he set out to stand up the company. With an authorized strength of about 200 soldiers and officers, his recruitment process defied normal Army personnel assignment procedures by relying on word-of-mouth recommendations. He initially tapped into respected friends and colleagues for candidates. Ferguson recalls receiving permission from Hollingsworth to divert anyone he wanted already in Alaska to serve in the company and that the USARAL commander would intervene, if needed, to make it happen. Ferguson sought out candidates to fill the authorized billets. He later interviewed new Infantry arrivals personally to see if they were a good fit. “Anytime I saw a really good soldier, I’d steal him,” Ferguson said. “I made a lot of enemies,” but Hollingsworth made good on his promise to support his efforts.14

Ferguson only managed to recruit about 180 soldiers, but he was not worried. “I’d rather have 180 good people than 200 average people.” Those that later proved not to have the mental, physical, or moral fortitude nor the right attitude or values were reassigned. If they were “sullen, didn’t follow directions, cut corners, didn’t obey NCOs, or talked bad about NCOs,” they would be cut. “It took us about two months to gather enough equipment, find the barracks for us, get our parachutes, (get) people qualified, and in about three months we became operational,” Ferguson said.15

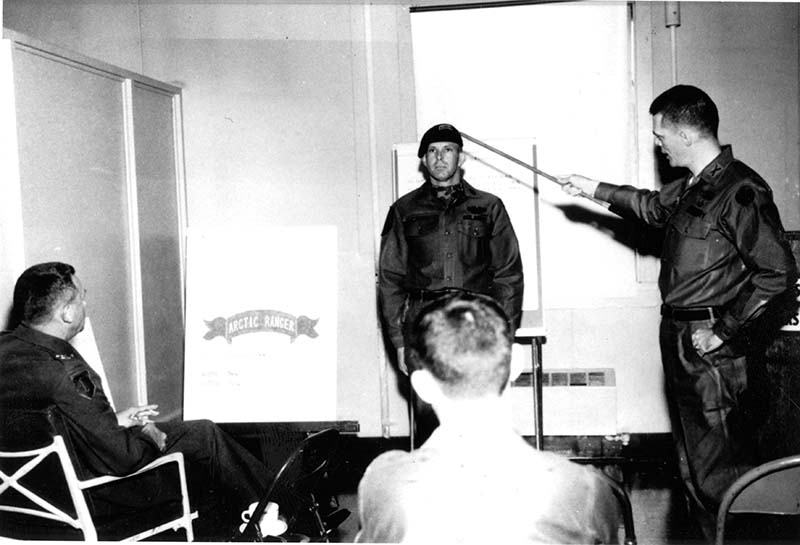

Ferguson first established the Arctic Ranger School – a three-week course required for all unit personnel that was modeled after the Army’s Ranger school curriculum at Fort Benning, Georgia. The Arctic Ranger School taught basic Ranger skills, communication, mountaineering, survival, long-distance patrolling, and weaponry, with extra emphasis on cold-weather tactics. Soldiers with Ranger qualifications led the training. Soldiers learned how to use snowshoes and skis and incorporated lessons from the native Alaskan Eskimo Scouts on hunting and survival. The Arctic Ranger School was unit-level training and not formally approved by the Department of the Army, but Ferguson wanted to make sure his men were prepared for any situation. Future unit members came with Ranger qualifications.

A Test of their Skills

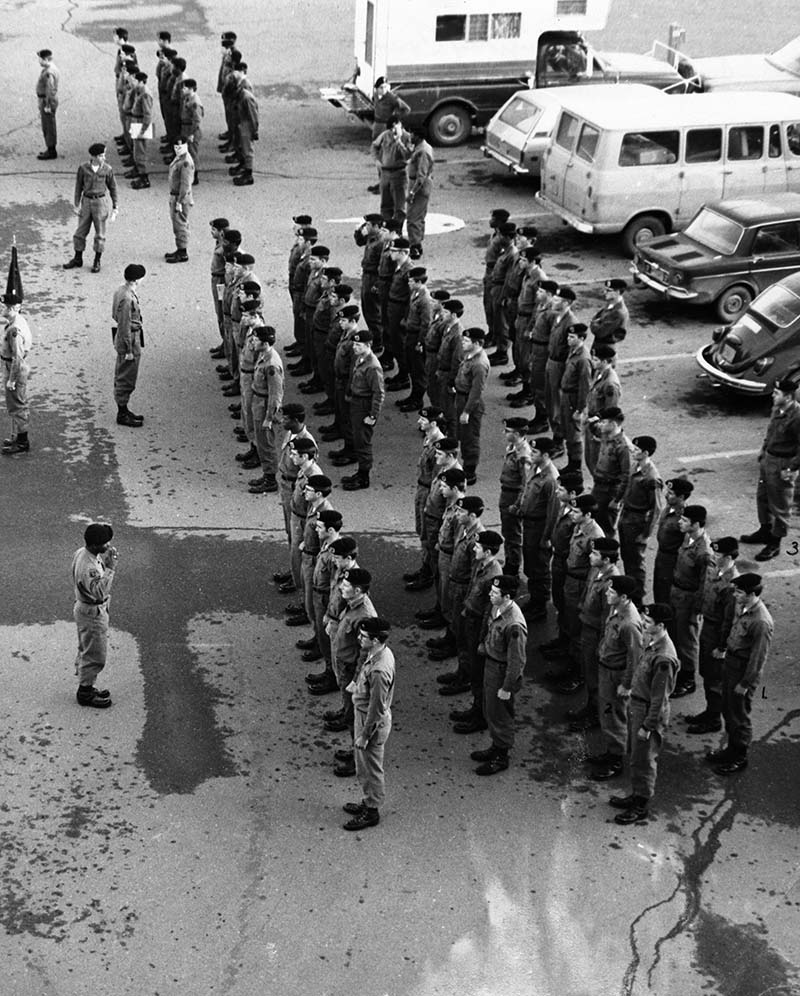

From September to December 1970, Company O participated in a variety of training exercises designed to test their core abilities. This included the annual USARAL exercise, ACID TEST III. Below is a summary of some of the unit events during that four-month period:

- 23 September – The Arctic Rangers conducted an airborne assault then linked up with the Eskimo Scouts to get situational awareness and conduct reconnaissance on the enemy role players. At the bottom of the typed operational order, Ferguson hand wrote, “Challenge and Password for link up.” The LRRP phrase was, “This is a high mountain,” while the Eskimo Scouts would respond, “Not as high as some others.”16

- 19-21 October – Field Training Exercise 1-70 consisted of “living in marshalling area in tents South of Claxton Drop Zone, organizing and receiving night aerial resupply, performing reconnaissance of selected targets and patrolling.”17

- 26 October – Conducted cold weather and ski training at Independence Mines.18

- 2 December – Convoyed to Fort Greely for winter maneuvers, along the way practicing radio communication and determining feasibility of primary and alternative routes in preparation for winter maneuver ACID TEST III.19

- 5-12 December – The Arctic Rangers integrated into ACID TEST III, which included forces from the 171st Infantry Brigade. The Rangers conducted long and short-range reconnaissance patrols to gather information on enemy movements, played by the Canadian 20th Fusilier Regiment.20

Military Firsts

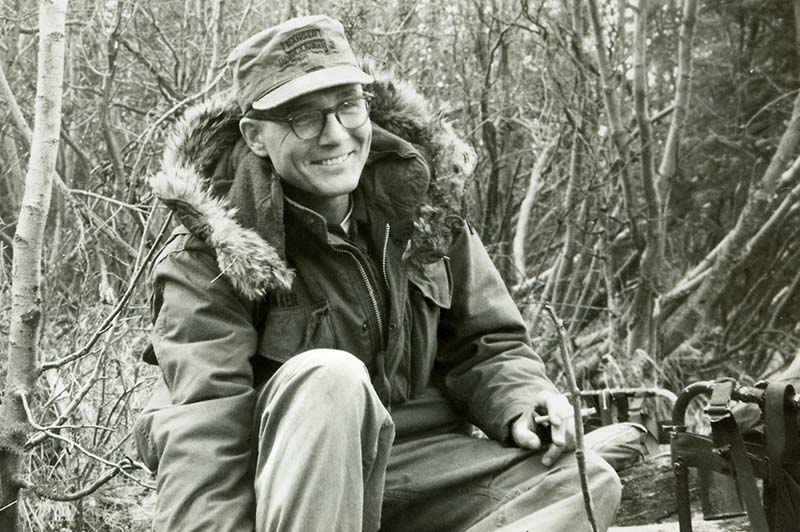

The operational tempo ramped up considerably in 1971 as the Arctic Rangers continued to support USARAL while seeking out opportunities to push physical and mental boundaries, according to the unit history. “The year was characterized by diversity in training, which saw the Company virtually spanning the length and width of Alaska, in pursuit of Dynamic Arctic Training (formerly known as ‘adventure training’).” The drills consisted largely of basic and advanced mountaineering skills, river navigation, and arctic winter tactical maneuvers.21

Larry Lee, then a private and among the initial group of men recruited by Ferguson, spent 15 months with the Arctic Rangers as an assistant radio operator. He recalled their emphasis on “learning how to survive in sub-zero temperatures,” which included skiing and using snowshoes, dealing with extreme cold, finding and purifying water, and keeping equipment, including radios and heaters, operational. He remembered, “One of the major issues in extreme weather is survival. If you can’t survive, nothing else matters.”22

In addition, Company O organized and led airborne courses for USARAL starting in 1971. “Company O planned and carried out the first Basic Airborne Course in the history of USARAL. The course began on 11 January 1971 and was comprised of 64 students.” All but four graduated. Four additional airborne courses, including two jumpmaster courses, were conducted that year, with about 200 soldiers earning their jump wings. The airborne school continued into the next year and provided basic airborne and jumpmaster classes for both the unit and conventional force soldiers in Alaska.23 Lee was among the students in the first airborne course, which graduated on 29 January 1971, just in time to be part of the unit’s next adventure.24

As Hollingsworth’s confidence in Company O grew, he envisioned the Arctic Rangers as the “reactionary force” to lead in Polar Ice Cap rescues in the event aircraft went down in the area. “To prepare for the role, on 4 March 1971, Ferguson and his company parachuted about 130 miles northeast of Point Barrow, Alaska, to conduct a simulated rescue operation. Twenty-one hours later, after a successful exercise, the company was extracted by CH-47 Chinooks.25 The success of the exercise reached the Army Chief of Staff, General William C. Westmoreland, who sent a congratulatory telegraph to then Major General Hollingsworth. “I am pleased to learn of the successful completion of ACE BAND-POLAR CAP. This type exercise is well suited to your Arctic Ranger company. The training received will certainly prove invaluable, should rescue assistance ever be necessary in inaccessible areas of Alaska or on the arctic ice pack” Westmoreland visited Alaska later in 1971 and personally congratulate the company.26

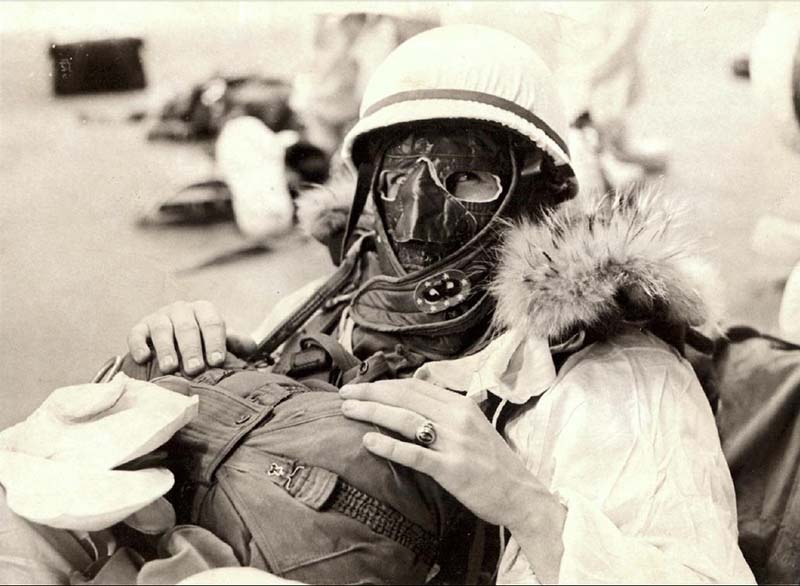

Ferguson later recalled that the jump was delayed due to an “ice quake that broke up the ice floor.” When they did jump, the soldiers had to be ready for much more than tangled parachute lines. They had to deal with brutal wind chill and the “king of the Ice Cap” – polar bears. At minus 10 degrees Fahrenheit and a wind chill of minus 70, frostbite was also a major concern. On the second day, Ferguson recalled MG Hollingsworth coming out to greet the men and congratulate them on their success. One of the men took off his glove to shake the general’s hand, got frost bite, and had to be evacuated. Fortunately, they did not have to worry about polar bears on this jump.27

On 29 October 1971, Ferguson relinquished command to Major Edward O. Yaugo, the second and final commander. He considers himself a lucky man to have commanded the Arctic Rangers.28 That winter, with Yaugo now in command, word about Company O’s unique mission made its way to Fort Benning. There, Second Lieutenant (2LT) Charles “Chuck” Coaker, wrote then-USARAL commander, Major General Charles M. Gettys, requesting assignment to the Arctic Rangers. Within weeks, his request was approved and he received orders to report to Company O.29 Coaker signed into the unit and quickly noticed a unique bond because they all were all doing something different and special. The unit was more diverse than he expected, with a blend of combat-tested Vietnam veterans and newly minted officers and NCOs of varied backgrounds and ethnicities.

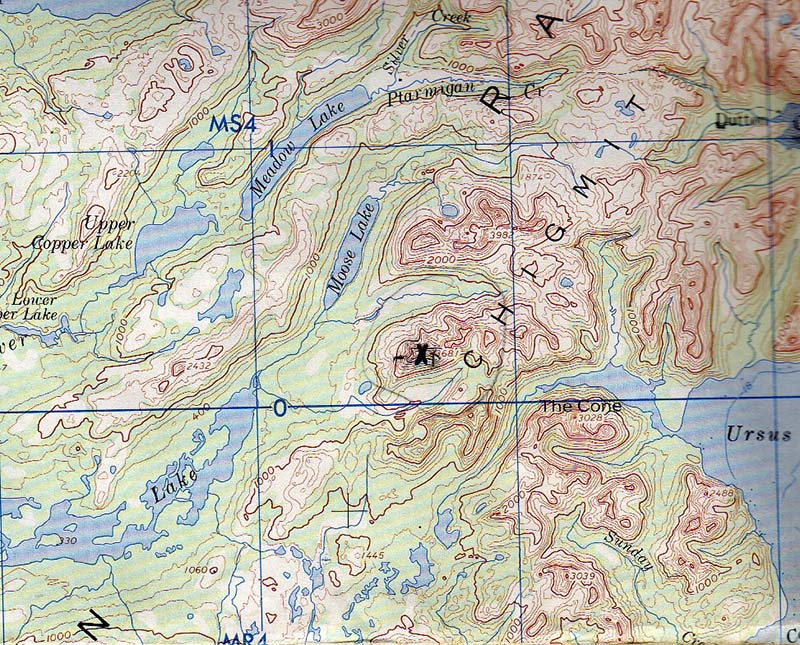

At the time of Coaker’s arrival, the unit operated in three platoons, each covering a portion Alaska. Coaker received command of 1st Platoon, which operated in the northern area from the Arctic to Brooks Range. Second Platoon covered the area from Brooks Range to Anchorage, and 3rd Platoon had Anchorage to the Canadian Coast. Each platoon had roughly 40 men, divided into self-sufficient five-man teams that could conduct separate reconnaissance missions.

The next eight months were spent on relentless training. Coaker’s platoon crossed the Harding Icefield, jumped onto the Polar Ice Cap, lived off the land with the Eskimo Scouts, and scaled dangerous glaciers. Coaker said it was thrilling. “If you were a civilian, you would pay thousands of dollars to go on one of these adventures.” The adventures did not come without risk, and injuries were common. Coaker recalls a close call near the end of a three-week training exercise, in which his partner was seriously injured. “Mother nature is not very forgiving in Alaska. People very often come out on the short end of the stick.”