DOWNLOAD

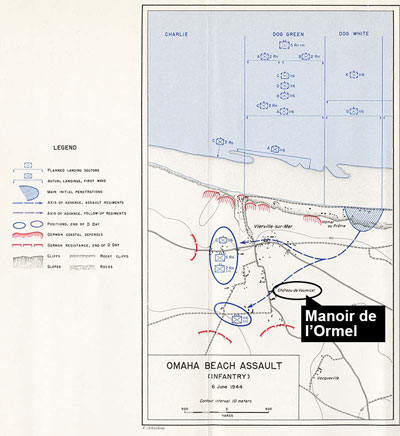

In June 2023, the U.S. Army Special Operations Command (USASOC) leadership visited Normandy to participate in the commemoration of the 79th anniversary of D-Day, the Allied invasion of Nazi-occupied France. Because of the size of the party and the lack of hotels in the region, it was more economical to secure a house for lodging. The Manoir de l’Ormel was central to all the events and speaking engagements that the Command Group planned to attend. Unbeknownst when reserved, it also had a place in Army Special Operations history. This one house’s story helps illuminate the Rangers’ shared history with the Virginia Army National Guard’s 116th Infantry Brigade Combat Team, 29th Infantry Division. To learn that story, one must turn back time to World War II.

France fell to Nazi Germany in 1940. As the war went on, the Allies knew they had to get back into northern Europe to defeat Germany but there were no good options, as the Allies had learned in the failed Dieppe raid on 19 August 1942. The Nazis had spent years building coastal defenses from the French border with Spain to the northern tip of Norway. Dubbed the “Atlantic Wall,” this system of reinforced bunkers, fighting positions, and defensive obstacles presented an incredible planning challenge to the Allies. All potential landing areas were defended by emplaced artillery and machine gun positions, manned in some cases by veteran troops. Such was the case with OMAHA Beach, one of the two landing beaches assigned to U.S. forces for the planned invasion of Normandy.

OMAHA was the code-name given to a beach landing zone almost five miles wide. A successful landing there would link U.S. forces landing to the west, at UTAH, and British forces to the East, at GOLD. However, the beach itself was an obstacle. At low tide, when the Allies intended to land, it had a large sandy area, filled with emplaced antitank and antipersonnel obstacles, that was approximately 300 yards deep. This ended with a shelf of rocks, approximately eight feet high, backed by a seawall. Then, another 200 or so yards of open terrain ended in steep bluffs, up to 150 feet in height, and protected with rows of barbed wire. U.S. forces would have to cross this stretch of beach while facing direct fire from German machine guns in fortified positions.

To break the German defenses, the U.S. developed a staged plan. First, Allied ships would pour naval gunfire onto the landing area with a short but intense barrage. Then, aircraft would bomb the beaches and bluffs to incapacitate the remaining defenders and blow holes through the obstacles. Following the bombings, M-4 Sherman tanks specially modified for amphibious operations would ‘swim’ to shore. Five minutes after the tanks hit the beach, troops would land in the first of multiple waves. However, on D-Day, 6 June 1944, things did not go as planned. The seas proved so rough that many of the tanks either sank soon after launch or had to be brought to shore by landing craft. There, they were sitting ducks and had to wait for the infantry to land.

OMAHA was broken into eight separate code-named sectors. Farthest to the west was CHARLIE, DOG GREEN, then DOG WHITE. Company A, 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Infantry Division, landed first at DOG GREEN. Those unlucky soldiers walked into a hell storm. Packed into six British Landing Craft Assault (LCA), the soldiers of Company A made their way to shore. At 1,000 yards out, the first boat went down, leaving five boats to drop their ramps on the beach at approximately 0630 hours, designated as H hour. The Germans rained machine gun fire onto the beach as the men piled out into waist deep or higher water. Soldiers, many wounded, jumped into the water to escape the gunfire. Many drowned as they were carried to the bottom by the weight of all the equipment they carried. The survivors vainly struggled to conceal themselves in the water or behind beach obstacles, where they were slowly picked off. Within fifteen minutes, Company A was no longer a fighting force and few soldiers from Company A survived the day unscathed.1

The sixty-five men of Company C, 2nd Ranger Battalion landed on CHARLIE just fifteen minutes later. Seeing the chaos on DOG GREEN, they did not hesitate at the water’s edge, but rushed to the base of the cliffs. About half managed to cross the beach, where they huddled against the cliff face. After a brief pause, the Rangers began to climb the steep cliffs. Once at the top, the Rangers started eliminating German fighting positions. This helped alleviate the enemy fire being placed on succeeding waves of American troops.2

Back at DOG GREEN, Company B, 116th Infantry, followed Company A and landed at 0700 hours. However, its boats were widely scattered. Two boats landed their troops at the same sector as Company A. Those soldiers met with the same stiff opposition. The other LCAs landed their troops to the far left and right of DOG GREEN. The soldiers that landed to the right joined the Rangers of Company C and fought with them for the rest of the day. Four boats veered to the left. One, whose troops were led by Second Lieutenant (2LT) Walter P. Taylor, landed near Hamel-au-Prêtre, where the beach was relatively clear. Taylor led his twenty men over the seawall, losing four killed. The group infiltrated through a gap in the barbed wire and, joined by other survivors from Company B, made their way into Vierville-sur-Mer. The twenty-eight-man force headed to their rallying point at the Manoir de l’Ormel.3

Following Company B, 116th Infantry, came Companies A and B, 2nd Ranger Battalion, and the entire 5th Ranger Battalion. These two companies of the 2nd Rangers landed at the ill-fated DOG GREEN and went into the same maelstrom as the prior units. Seeing this, the combat-hardened commander of the 5th Rangers, Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Max F. Schneider, ordered the coxswains of the boats carrying the 5th Rangers to land instead to the left at DOG WHITE, where the enemy fire was much lighter.4 The 5th Rangers landed at 0715 hours, and made it mostly intact as a unit to the seawall.5

It was there, while huddled with troops from the 116th Infantry, that Brigadier General Norman D. Cota, Assistant Division Commander, 29th Infantry Division, ordered the 5th Rangers to get over the seawall and lead the way.6 Therefore, “at a signal from the Battalion Commander [LTC Schneider], the leading echelon scrambled over the wall, blew gaps in the protective wire, and protected from enemy observation by the curtain of rising smoke advanced unhesitatingly to a point near the top of the hill.”7 After taking out defensive positions at the top, the way was now cleared for troops at DOG WHITE to get off the beach.

The Ranger’s pre-invasion directive was to get ashore and then head west to assist Companies D, E, and F, 2nd Rangers, which, under the leadership of LTC James E. Rudder, had seized the German strongpoint at Pointe Du Hoc. With this prior directive, First Lieutenant (1LT) Charles “Ace” Parker, commanding Company A, 5th Rangers, immediately went inland through the smoke to the rallying point, also the Manoir de l’Ormel. However, once past the beach, LTC Schneider paused to consolidate the rest of his men. Unlike 1LT Parker’s Company, they encountered stiff opposition and moved into Vierville. There, COL Charles D. W. Canham, the 116th Infantry commander, pressed the Rangers into helping secure and then defend the town. 1LT Parker and his Rangers were on their own.8

While this was happening, 2LT Taylor and his men were making their way overland to the Manoir. Just as the Rangers were experiencing, they encountered the first of the Normandy bocage. These thick hedgerows between small farming fields hid enemy movement and were ideal defensive positions from which the Germans could engage. In addition, because the Germans used smokeless powder, it was extremely difficult to discern their firing locations. This slowed the advance as 2LT Taylor’s group cautiously followed the coastal road into Vierville-sur-Mer.

As 2LT Taylor’s group neared their rally point, they took enemy fire from the field to the left of the Manoir, suffering three wounded. The U.S. soldiers worked their way along the hedgerow, and then countered with small arms fire and grenades. One of the grenades exploded in an enemy foxhole. A German soldier “screamed at top voice and that ended the skirmish. The other fourteen surrendered.”9 2LT Taylor detailed one of his few men to escort the prisoners back to the beach.

The rest secured the Manoir de l’Ormel, where they captured a German doctor and his aid man. According to the 116th’s after-action report, “Taylor put them on a kind of parole and left his three wounded in their charge.”10 Seeing no other U.S. troops in the area, the Company B soldiers pressed further south to the crossroads just past the Manoir. As they moved forward, three truckloads of German soldiers deployed. The much larger enemy force engaged 2LT Taylor’s force, placing them in danger of envelopment.

Things went from bad to worse when another three soldiers were wounded, one killed, and the squad Browning Automatic Weapon (BAR) lost.11 This is where 2LT Taylor’s unique background came of use. In 1936, he had been an exchange student in Germany and attended the Nationalpolitische Erziehungsanstalten [National Political Institutes of Education] at Plön.12 The school, like others in the system, was heavily militarized and designed to indoctrinate and produce future Nazi leaders. On D-Day, this experience had served Taylor well as, according to his son, he was able to call out to the Germans in their own tongue to be soldierly and let him retrieve his wounded man. Perhaps startled by fluent German coming from a U.S. soldier—as were 2LT Taylor’s men—the enemy complied.13 Their wounded secured, the small U.S. force retreated to the Manoir. Constructed of thick stone walls, with periodic view slots in the wall itself, it was an ideal defensive position. Despite having lost their only automatic weapon, the much smaller force managed to hold off the enemy. Just when worries arose about running out of ammunition, help arrived in the form of 1LT Parker and 23 Rangers.

1LT Parker’s men had made their way to the Chateau by following a drainage ditch in a farm field.14 They had been forced to crawl through the ditch because German fire had pinned them down, killing one and wounding another. After three and half hours of crawling to get past the German gunfire, the Rangers made it to the Manoir de l’Ormel around noon. This was just in time to help 2LT Taylor and his Company B, 116th Infantry soldiers beat off the German attack.15

Once the enemy was driven off, each of the two elements reverted to their separate missions. When no other Rangers came to the rally point, 1LT Parker decided he had arrived late and had to catch up with the rest of the Ranger force. He and his small unit set out for Pointe Du Hoc. On the way they engaged several small groups of Germans, capturing about twenty. As they got closer to the Pointe, the Rangers encountered stronger enemy forces. Because they could not infiltrate through these troops saddled with prisoners, 1LT Parker simply let them go. He said later, “I was not going to murder them. They had no guns.”16 The Rangers decided to leave the roads and paths they had been following and went overland to get to the 2nd Rangers. As they were moving, a voice called out in English, “What’s the password,” to which 1LT Parker answered “Tallyho.” A welcome sight to the beleaguered 2nd Rangers, Parker and his men were immediately assigned a sector in the small defensive perimeter around Pointe du Hoc. It was then that they learned that, instead of being the last of the 5th Rangers to make it to Pointe du Hoc, Parker and his men were the first and only Rangers who landed on OMAHA Beach to complete their assigned objective.17

Meanwhile, 2LT Taylor led his force to the southwest, near Louviéres. He had moved the furthest south of any troops to make it off the beach near Vierville-sur-Mer, when he received word to pull back into the town to help secure the perimeter.18 Ironically, he was with the combined 2nd/5th Ranger, 116th Infantry, and 743rd Tank Battalion force that relieved LTC Rudder and his Rangers, including 1LT Parker, on 8 June.

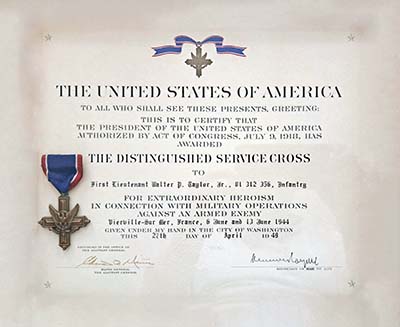

In conclusion, the Manoir de l’Ormel, originally selected as a convenient place to stay for the USASOC Command Group’s visit on the 79th anniversary of D-Day, had a secret of its own. Seemingly just another stone mansion, it was in fact a pivotal location near OMAHA Beach where two groups of brave soldiers pressed the farthest inland of any unit that day and repelled a German counterattack. This story highlights the shared history of today’s 75th Ranger Regiment with the Virginia Army National Guard’s 116th Infantry Brigade Combat Team, 29th Infantry Division. It also tells the amazing story of two young officers from two separate units, who both managed to achieve their D-Day objectives despite facing enormous challenges. For their actions on 6 June 1944 and the days that followed, these young officers also received the second highest award for valor, the Distinguished Service Cross. Their citations are as follows:

First Lieutenant Charles H. Parker

“For extraordinary heroism in action on 6th, 7th, and 8th of June, 1944 from Vierville-sur Mer to Le Pointe du Hoc, France. In the invasion of France, Lieutenant Parker led his company up the beach against heavy enemy rifle, machine gun and artillery fire. Once past the beach he reorganized and continued inland. During this advance numerous groups of enemy resistance were encountered. Through his personal bravery and sound leadership this resistance was overcome, and the company succeeded in capturing Le Pointe du Hoc, the Battalion objective. The following morning, Lieutenant Parker led a patrol through enemy territory in an effort to establish contact with the balance of the Battalion. Lieutenant Parker’s valor and superior leadership are in keeping with the highest traditions of the service.”19

Second Lieutenant Walter P. Taylor

“For extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against the enemy. On 6 June 1944, Lieutenant Taylor landed with his boat section near Vierville-Sur Mer, France and led his men on to their initial objective through enemy machine-gun, artillery and mortar fire. After being joined by another section, Lieutenant Taylor and his group headed for the predetermined battalion rendezvous area. In this move one of his men was wounded. Disregarding his own personal safety and in the face of enemy fire, Lieutenant Taylor moved to aid the wounded man. In so doing his weapon was shot from his hand, but he courageously proceeded in his task and evacuated the wounded man to safety. During the following days, Lieutenant Taylor displayed inspiring leadership and outstanding courage as he skillfully led his men in numerous advances on enemy positions. At one time he led the spearhead of a battalion attack across a river and a heavily fortified enemy-held hill. On 13 June 1944, Lieutenant Taylor was wounded but his display of skillful, courageous leadership contributed immeasurably to the success of his unit and was the source of inspiration for his men. The extraordinary heroism and courageous actions of Lieutenant Taylor reflect great credit upon himself and are in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service.”20

Thank you to Mr. Geoff Taylor, son of 2LT Walter P. Taylor, for providing items from his father’s estate. Thank you also to Mr. Ron Hudnell for providing copies of Parker’s and Raaen’s books. Mr. Hudnell is the driving force behind the effort to recognize the WWII Ranger Battalions with the Congressional Gold Medal. Finally, thanks to Mr. Al Barnes, Virginia Army National Guard Command Historian, and Mr. Joseph Balkoski, former Maryland National Guard Command Historian, for their assistance.