“The mission of a ranger company as prescribed by [the] Department of the Army is to infiltrate through enemy lines and attack command posts, artillery, tank parks and key communication centers or facilities.”1

DOWNLOAD

When the North Korean Peoples’ Army (NKPA) invaded South Korea on 25 June 1950 the United States Army realized that its ability to defend and counterattack was extremely limited based on the massive demobilization of forces after World War II. Specialized units like the Rangers, Merrill’s Marauders, and First Special Service Force, trained to “take the war to the enemy” behind the lines by disrupting rear area operations and interdicting lines of supply and communication were deactivated by 1945. In July and August 1950, the Far East Command (FECOM) reacted to the situation in Korea by creating TDA units like the 8th Army Ranger Company and the General Headquarters (GHQ) Raiders from occupation forces already stationed in Japan. In September 1950, Army Chief of Staff General (GEN) J. Lawton Collins, announced his intent to activate and assign one Ranger Infantry Company (Airborne) [RICA] to every active U.S. Army and National Guard infantry division.2 The purpose of this article is to describe how one of these, the 6th RICA, performed a deterrent role in Europe rather than a combat assignment in Korea.

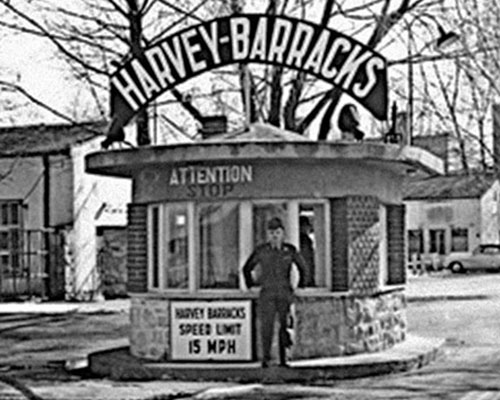

The first step in putting GEN Collins’ concept into action occurred on 15 September 1950. The Commandant of the Ranger Training Center (RTC), Fort Benning, Georgia, Colonel (COL) John G. Van Houten, reported to the Chief of Staff, Office of the Chief, Army Field Forces and was informed that training of Ranger type units was to be initiated at the earliest possible date.3 Simultaneously, an announcement was made Army-wide calling for Ranger volunteers. The RTC received the first group of volunteers, divided them into four companies, and started training them as company-sized units on 2 October 1950. Finished by 13 November 1950, these men formed the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th RICAs, and were already on their way to Korea when the 5th, 6th, 7th and 8th RICA volunteers started their training cycle.4 The officers and men who formed the 6th RICA, traced their lineage and honors from World War II’s Company B, 2nd Ranger Battalion, were assigned to the Regular Army on 2 November 1950, and formally activated on 20 November 1950.5

Almost from its first formation at Fort Benning, the 6th started earning a reputation as a ‘one-of-a-kind’ unit even among the other Ranger companies. One of the principal reasons for this was the WWII veterans who filled the company’s three top leadership positions. Chosen to command the company was Captain (CPT) James S. ‘Sugar’ Cain. CPT Cain earned his battlefield commission as a member of the First Special Service Force (FSSF) in 1944. Assisting him was CPT Eldred E. ‘Red’ Weber, the company executive officer. Starting as a member of the 1st Ranger Battalion (‘Darby’s Rangers’), CPT Weber was transferred to the FSSF when the Rangers were disbanded in 1944. Completing the company’s command team was its senior non-commissioned officer (NCO), First Sergeant (1SG) Joseph Dye, Sr. 1SG Dye’s combat record included Ranger assignments from Dieppe, France, in 1942, through North Africa, Sicily, Salerno, and Anzio, and Cisterna, Italy, in 1944.6

With the company headquarters established, the remaining spaces in the platoons were filled by men looking for the challenges, opportunities, and excitement that Ranger units provided. By convention, those assigned to the 6th RICA came through the normal ‘volunteer pipeline’ in no particular order. This process was the same for the officers as it was for the enlisted men. For example, Second Lieutenant (2LT) Clarence E. ‘Bud’ Skoien, 11th Airborne Division, Fort Campbell, Kentucky; First Lieutenant (1LT) Robert B. ‘Buck’ Nelson, 82nd Airborne Division, Fort Bragg, North Carolina; and CPT William S. Culpepper, 7th RICA, Fort Benning, Georgia, were all assigned to the 6th RICA as platoon leaders with little more than peace-time Army garrison experience.7 On the other hand, a greater number of the enlisted men like MSG Eugene H. Madison reported for duty with either combat, post-war Regular Army experience, or both.8 Through the combined efforts of the RTC cadre, CPT Cain, CPT Weber, and 1SG Dye, the knowledge gap between the two groups was soon non-existent.

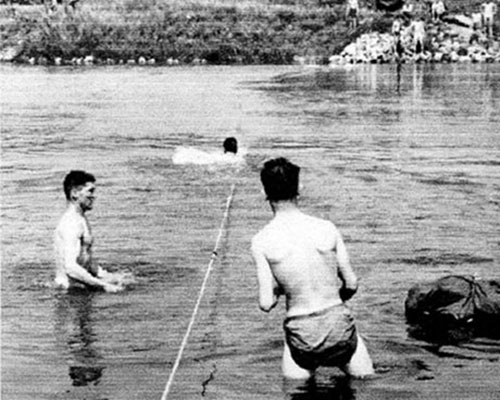

Fully assembled at the RTC, the 6th RICA started training on Monday, 27 November 1950. Faced with the knowledge that training time was a precious resource not to be wasted, CPT Cain instituted eighteen-hour duty days by augmenting the RTC training schedule with additional off-duty classes that ensured that every man was as fully familiar with every subject being taught as possible.9 Private First Class (PFC) Edmund Kolby remembered that “both officers and non-commissioned officers were up at 0400 hours every morning and spent more time in the field than in the classrooms.”10 Individual physical, weapons, and tactical training were supplemented with other subjects like escape and evasion, village fighting, adjustment of artillery fire, and squad and platoon tactics. As an added task, each man’s swimming ability was tested, and those who were weak or could not swim were given sufficient ‘extra’ time to practice and develop their proficiency.11

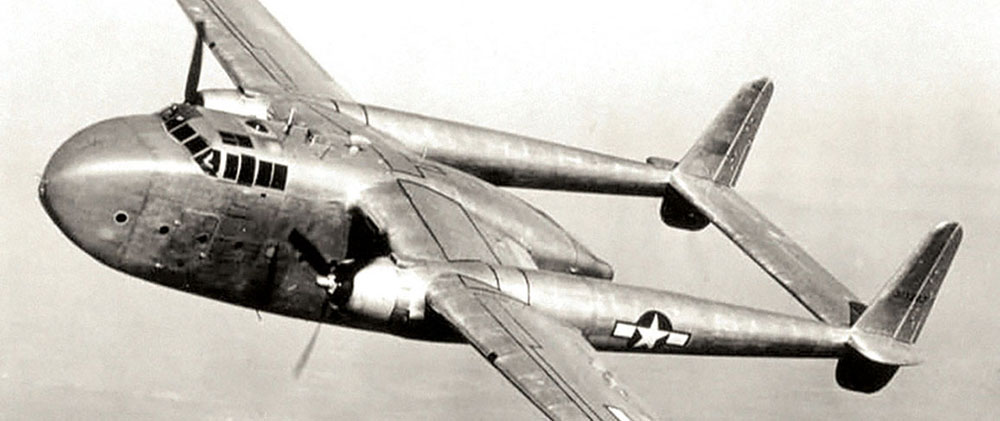

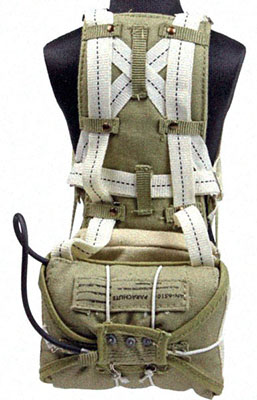

After six weeks of exhausting marches, physical exercises, long hours, and little sleep, the 6th RICA prepared for its final evaluation. To measure how well the Rangers were able to perform individual and unit missions, the RTC implemented a five-day field training operational readiness test (ORT).12 Designed to meet specific training objectives, the test started with a night, low-level, tactical parachute drop. This was followed by individual platoons conducting drop zone assembly procedures, night tactical movements, and locating and destroying a series of bridges. With that completed, the platoons moved on their own at night into a designated area, reassembled into a company element, performed a final night tactical march, and attacked a company-sized objective located on a piece of key terrain.13