DOWNLOAD

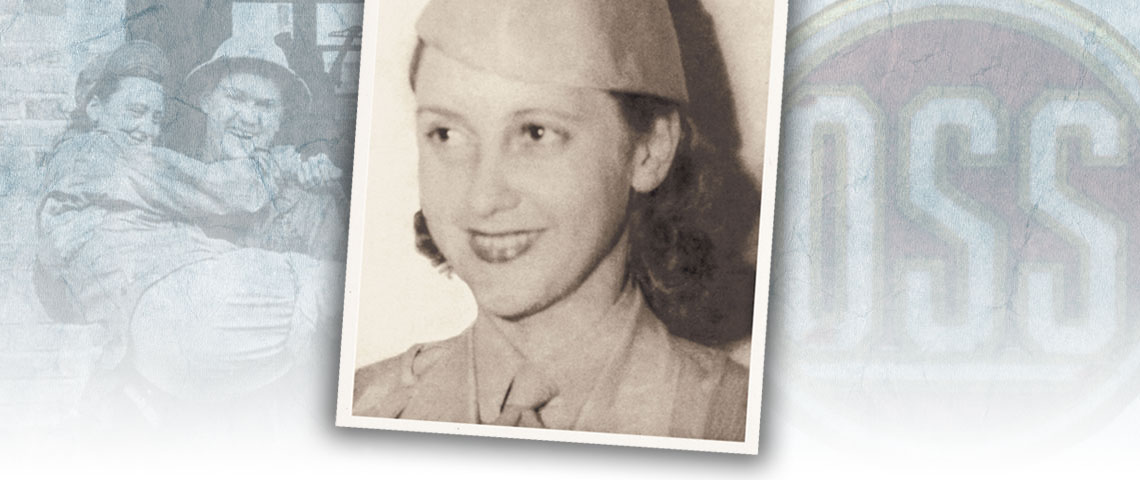

On 8 June 2015, Elizabeth P. McIntosh passed away at the age of 100.1 Although she led a full life, within the Army Special Operations community she is most remembered for her World War II service. As a civilian in the Morale Operations (MO) Branch of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), McIntosh was one of the first females to conduct Psychological Operations overseas.

The OSS, created on 13 June 1942 and headed by William J. Donovan, had a two-fold mission. First, it collected, analyzed, and disseminated foreign intelligence. Second, it conducted unconventional warfare. This last function included psychological warfare, under its MO Branch. Donovan believed that “persuasion, penetration, and intimidation” were modern day counterparts to “sapping and mining in the siege warfare of former days.”2 For MO, this meant employing false rumors, leaflets, documents, and radio broadcasts to undermine “the morale of the enemy.”3 As such, MO produced and disseminated ‘black’ propaganda on both a strategic and tactical level in an attempt to destabilize enemy governments and encourage resistance movements. McIntosh was an ideal candidate for such work.

Born in Washington, D.C., on 1 March 1915 to parents who were journalists, Elizabeth Sebree Peet, had the family business in her blood. In 1935, she graduated from the University of Washington, School of Journalism. By 1941, she was married to fellow journalist Alex MacDonald, and had already worked for the Honolulu Advertiser and the Star Bulletin.4 Because both wanted to go to Japan, they prepared for two years by living in a Japanese household and learning to speak the language.5 The war prevented their plans to live and work in Japan.

Her first exposure to war was when she witnessed firsthand the 7 December 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. She remained a journalist in Hawaii until 1943 when “the Scripps/Howard news service picked me up … and sent me to Washington [D.C] to cover the White House and write a daily column.”6 There, in 1943 while interviewing an old friend of her father’s who happened to be in the OSS, she was asked to join. After completing training in OSS fieldcraft and MO techniques, she arrived in New Delhi, India in July 1944. There, she served in the MO office of Detachment 303, the OSS rear area administrative base for the Southeast Asia Command (SEAC).

While at Detachment 303, McIntosh’s MO unit supported Detachment 404, the operational OSS element for SEAC. She learned to work with many partners in order to produce products. For example, her work included convincing Japanese POWs to help proofread fake orders to ensure that they had the proper language and syntax. Then, the MO section had to coordinate with British officials for access to the correct types of paper and offset presses to convincingly create products that matched those of the enemy. Her MO office also provided products for OSS Detachment 101 in Burma, considered by the OSS to be its “most effective tactical combat force.”7

MO support to Detachment 101 is illustrated by this example from February 1945 in central Burma. The Detachment 303 MO section forged an order supposedly from the Japanese high command, reversing a no-surrender policy by declaring that soldiers could surrender if they were cut off, without ammunition, or incapacitated. They placed the fake document in a genuine Japanese dispatch case. A native agent then turned the case over to a Japanese military police headquarters at Maymyo, claiming to have found it beside a wrecked vehicle on the Mandalay-Maymyo road.8 Other Detachment 101 agents slipped another copy of the same false orders into the headquarters of a Japanese infantry regiment. The MO Section followed these plants with a rumor campaign and then arranged an airdrop of leaflets near the Allied lines that purposefully fell on Japanese positions. Although meant for the Japanese, this leaflet directed Allied troops to treat Japanese prisoners well.9 The hope was that this would provide further proof to the Japanese about the authenticity of the fake order.

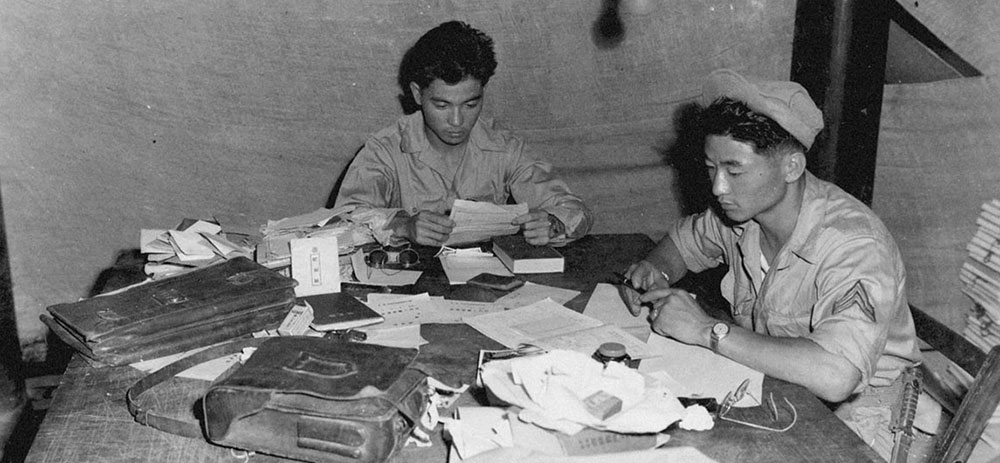

In another example, the Detachment 303 MO section discovered several hundred farewell postcards handwritten and addressed by Japanese soldiers. The cards had already been censored by the Japanese, but had been captured before they made it into the enemy mail system. The MO section, with the help of OSS Nisei (Japanese-American personnel), erased and rewrote the letters. The ‘new’ postcards now had anti-patriotic messages that asked their families at home why they lacked supplies at the front while telling them about “heartbreak and starvation in the jungles.”10 Once rewritten, Detachment 101 used its agent network to insert the postcards back into the Japanese mail system to directly penetrate Japan proper with a message of despair from the edges of the Empire.

McIntosh then went to China to serve with Detachment 202. There, she worked with artists and cartoonists in developing propaganda leaflets. In addition, she helped craft rumors designed to undermine Japanese morale that were then broadcast over the radio.

After the war, McIntosh briefly worked in journalism before embarking on a career writing nonfiction and children’s books. She divorced MacDonald, who served in Thailand with the OSS service and remained to found the Bangkok Post. She then married Richard Heppner, a lawyer for Donovan’s law firm and the former head of OSS Detachment 202. The year after Heppner’s death in 1958, she used her OSS connections to begin working for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). She served in the CIA until retiring in 1973. She spent much of the remaining years living in an old farmhouse outside of Leesburg, Virginia, and married her third husband, former WWII fighter pilot Fred McIntosh. Despite the brevity of her service in Psychological Operations, she was one of the few female UW practitioners to serve overseas with the OSS. Her WWII experience helped to break barriers and still serves as an inspiration for today’s Psywarriors.