DOWNLOAD

On 26 March 2003, 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment, together with Company B, 2nd Ranger Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment and other Special Operations Forces (SOF), raided a suspected chemical and biological weapons testing facility in central Iraq. Though the results of the collected samples were not disclosed, the special operations task force duly demonstrated the “fight like you train” principle in the search for the elusive smoking gun, the evidence that would demonstrate Iraq’s mass effect weapons program. The complicated mission was an illustration of precise planning, excellent training, and synchronistic execution. Every element of the task force performed its functions, especially contingency procedures, in a manner that prevented a disastrous ending, and saved the lives of two soldiers.

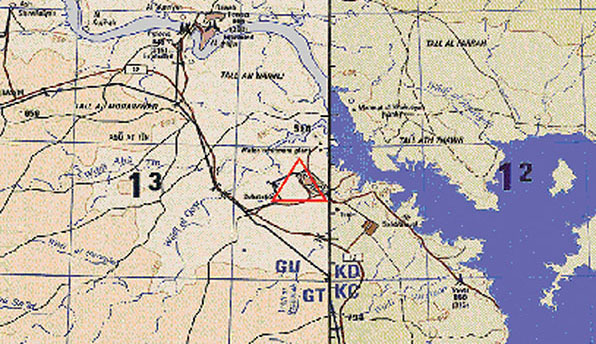

The Al Qadisiyah Research Center was a suspected chemical and biological weapons research complex along the southern shore of Al Qadisiyah Reservoir, approximately twenty-five miles northwest of the town of Hadithah. The United Nations Special Commission on Iraq failed to inspect the facility during its tenure; however, an intelligence assessment indicated that it warranted an investigation. The high risk mission was the domain of the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (SOAR) and the SOF elements it supported—Army Rangers and other special operations units. With its realistic and resolute training orientation, the SOF community was uniquely qualified to carry out such a high profile, and possibly high risk, mission.

Chief Warrant Officer 3 (CW3) Richard Hoyt (pseudonym), an MH-60K Black Hawk pilot and overall flight leader, received the assignment to plan the mission. It was a multifaceted mission requiring helicopter aerial refueling, en route linkups, precise preparatory fires, and sequenced landings, all performed in zero illumination conditions over an austere desert. Intelligence analysts predicted little organized resistance from the local populace, which led to displeased conjecture that the target was probably a “dry hole”—no evidence of weapons testing. However, military history is replete with the effects of complacency on the battlefield, and the environmental conditions can kill just as swiftly as a well aimed or errant round. Therefore, the SOF planners assumed they would encounter resistance and were confident that they would, in fact, find proof of an illegal weapons program.1

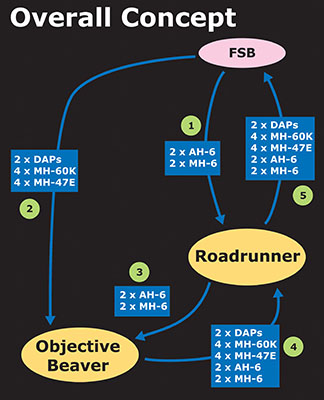

The plan emerged as follows: four MH-60K Black Hawks (referred to as Kilos) would insert Rangers into four blocking positions (BPs) around the objective; two MH-47E Chinooks (referred to as Echoes) would infiltrate the main assault force near the designated target building; two MH-60L Defensive Armed Penetrators (DAP) gunships, two AH-6 Little Bird gunships, and two MH-6 Little Bird sniper platforms would provide close air support around the target; and two additional Echoes would wait nearby ready to insert an immediate reaction force, or provide search and rescue if needed. The special operations task force was ready to execute within two days.2

On the night of 26 March 2003, CW4 Travis Buras (pseudonym) led the flight of MH-6 lift and AH-6 gunship helicopters to a desert landing strip (DLS) named Roadrunner. The DLS, which had been secured by the 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment a few days earlier, functioned as a forward arming and refueling position (FARP) and an emergency medical evacuation transfer site for this mission, since it was only thirty-five miles from the objective. Upon landing, Buras and CW4 Brian Ellis refueled, picked up four special operations snipers for the mission, and waited until their designed departure time. Two hours after the Little Bird flight departed, CW3 Hoyt took off from the FSB with his armada of aerial refuel (AR) capable aircraft for rendezvous with an MC-130P Combat Shadow tanker. Riding in the lead Chinook, Lieutenant Colonel John Cole (pseudonym), the air mission commander (AMC) and senior ranking Night Stalker, busily monitored the sequence of events with an execution checklist, which linked events with specific code words. He was the final on-site decision maker. The conditions for the assault on Objective Beaver were on schedule.

However, the initial rendezvous with the tanker foreshadowed the events of the night. The first tanker flew past CW4 Thomas Brady (pseudonym) in the lead DAP. This was not a good sign, because the mission was helicopter aerial refueling (HAR) dependent—it would have to be aborted if the helicopters were unable to aerial refuel. Fortunately, a second tanker moved into position, and Brady maneuvered his flight into position for fueling. During the refueling operation, Brady received a call from his colleague, CW4 Randall Ramsey (pseudonym), in a Joint Command and Control Aircraft. Ramsey informed him that a pair of A-10 Thunderbolt II aircraft were delayed on another aerial refueling track, and were unable to prosecute a target. Therefore, Brady’s new task was not only to cut the electricity from the power station on the city’s outskirts, but also to limit any collateral damage. Once his wingman had refueled, Brady departed the tanker and raced with only fifteen minutes left before H-hour (the time for the raid to occur): 2000 Zulu, or 2300 Iraq local time.3

Meanwhile, shortly after departing the HAR track, Hoyt spotted the flight of Little Birds on the horizon. The Little Birds had proceeded along a different route to Objective Beaver. The two separate flights conducted an often rehearsed aerial join-up without a hitch. As the Night Stalkers approached the release point—the point at which pilots cease following a designated route and freely maneuver in order to avoid potential threats—the Little Birds sped up to arrive at the target several minutes before H-hour in order to identify potential hazards or enemies. As the lights of the city partially illuminated the arriving gunships, various small groups of people rushed about on the ground or peered out windows, searching for the source of whining helicopters. In the lead AH-6, CW4 James Melvin (pseudonym) and his co-pilot feverishly looked for anyone who exhibited hostile intent, the prerequisite for launching an attack. Sixty seconds later, the pair of MH-6s arrived east of the objective, looking for belligerents but primarily focusing on the targeted building. The element of surprise had passed, and the next ten minutes on the objective became the most intense for all involved.4

Observing from an MH-6, CW4 Ellis saw sparks from small arms fire flying off the lead Black Hawk as it landed at BP1, but he could not identify the source. Then a vehicle drove up and parked directly in front of CW3 Hoyt’s helicopter. Luckily, the driver simply watched the events unfold as Army Rangers jumped from the helicopter and took up defensive positions. CW4 Melvin soon pinpointed the source of the gunfire. He immediately rolled in and fired a rocket right through the front door of the government building across the street from the landing zone (LZ). It was a spectacular close range shot and instantly eliminated the threat. As Hoyt departed, CW3 Harry Bateau (pseudonym) flew the second Kilo through a barrage of bullets half of a mile from the LZ. Sergeant (SGT) Owens, stationed at the left side window, automatically countered with his M134 minigun, sending a hail of 7.62 millimeter rounds back toward the enemy. Once they landed at BP2, Captain Todd Schultz noticed a large explosion in the distance to the south. Four kilometers southwest of the objective, Brady had just shot the first power transformer with his 30 millimeter M230 chain gun, and right behind him, CW4 Fred Hamilton (pseudonym) shot the second. Their attempts to limit collateral damage backfired, instead igniting the oil in the transformers and illuminating the previously dark sky from horizon to horizon. “It looked like a nuclear bomb went off,” according to CW3 William Moffit, who was hovering over the objective in the lead MH-6.5

Iraqi gunmen fired at the stationary helicopter, and a round entered through the cabin door, struck a Ranger in the back, exited through his chest, and then impacted his body armor.

The resulting fire had another unintended consequence; it silhouetted the remaining inbound aircraft. The Iraqis could now visually engage the decelerating helicopters. In spite of enemy gunfire, CW3 Peter Striker (pseudonym) managed to land the third Kilo at BP3 unscathed, though he narrowly missed a light pole with a timely rotation of the tail of the helicopter. The Rangers dismounted and raced into position as the last Black Hawk landed at BP4. Iraqi gunmen fired at the stationary helicopter, and a round entered through the cabin door, struck a Ranger in the back, exited through his chest, and then impacted his body armor. As the other Rangers leaped out the door, an accompanying Special Forces (SF) soldier’s gear got hung up and he stayed behind. Sergeant First Class John Pulley (pseudonym) and the SF soldier grabbed the wounded Ranger and began first aid. Wasting no time, CW3 Troy Schupp (pseudonym) pulled pitch, rapidly departing the area and radioing Hoyt that he had a wounded Ranger aboard.6

The Kilos quickly formed a flight en route and proceeded directly to Roadrunner, bypassing the planned checkpoints on the egress route. In the back of a blacked-out, bouncing helicopter, Pulley and SGT Jeremy Witts (pseudonym), both combat lifesaver qualified, applied a pressure dressing on the Ranger’s sucking chest wound, started an intravenous line of saline solution, and treated him for shock. Schupp landed the Kilo near a surgery-equipped C-130, and the crewmembers carried the Ranger to the airplane.7

The situation intensified as radio chatter about a casualty made its way up the chain of command. With the flight of Chinooks minutes away, CW4 Ellis restricted his flight path to a few hundred meters above a nearby hospital building. All of a sudden, a sniper aboard his aircraft calmly announced a target and dropped a gunman running toward the objective. The Little Bird was like a fifty-foot mobile deer stand.8 The inbound Chinooks carried the main assault force. Flying in the lead Chinook, CW3 John Foul (pseudonym) had been in this situation before, in the mountains of Afghanistan. Luck was on his side again as he flew through a salvo of gunfire to the LZ near BP3; even so, an enemy bullet struck a utility hydraulics line, which hindered aircraft control. The assault force rushed off the helicopter as soon as the ramp fell. Foul wrestled the helicopter into the air and began his egress.9

Responding to announcements of intermittent gun fire, CW3 Charles Adkins (pseudonym) automatically adjusted his Chinook’s flight path wide to the east and landed in the same place Foul had landed his Chinook. Staff Sergeant Michael Miller, stationed at the right ramp area, turned and shouted over the din of roaring engines the one minute time warning to the assaulters. He watched in amazement as rounds passed through the Chinook, miraculously missing everybody inside. More gunfire erupted from the buildings adjacent to the landing zone, and a round struck SGT Greg Eisner (pseudonym) in the head, knocking him backwards. Miller immediately dropped the ramp, and the assaulters exited in seconds. When all personnel were clear of the ramp, aircraft commander CW3 Casey Johansson (pseudonym) grabbed the controls, lifted off, and immediately joined the lead Chinook in its flight to DLS Roadrunner.10

The flight back to Roadrunner was fraught with tension, as CW2 Bunky Litaker and another soldier worked to save SGT Eisner’s life. The wounded flight engineer was still breathing, but was unconscious and had foamy blood coming out of his mouth. Working in the dark with a red lens flashlight, Litaker located the entrance wound above Eisner’s right maxilla and delicately applied a pressure bandage to the area. At the halfway point of the egress, Eisner suddenly stopped breathing. Yelling above the roar of the helicopter, Litaker and the other soldier began cardiopulmonary resuscitation, kneeling on the blood-slicked floor. After five exhausting minutes, Eisner opened his eyes, spat a bit of blood, and began to breathe on his own. Landing in a dust cloud at the DLS, pilot Johansson parked one hundred meters away from the specially configured C-130 medical transport. Litaker and two other crewmembers carried a blood-soaked Eisner to the Ranger security force guarding the airplane. The soldiers transferred Eisner to a litter and the Rangers took over from there, carrying him into the C-130. In short order, the airplane departed with both Eisner and the wounded Ranger from Schupp’s Kilo aboard.11

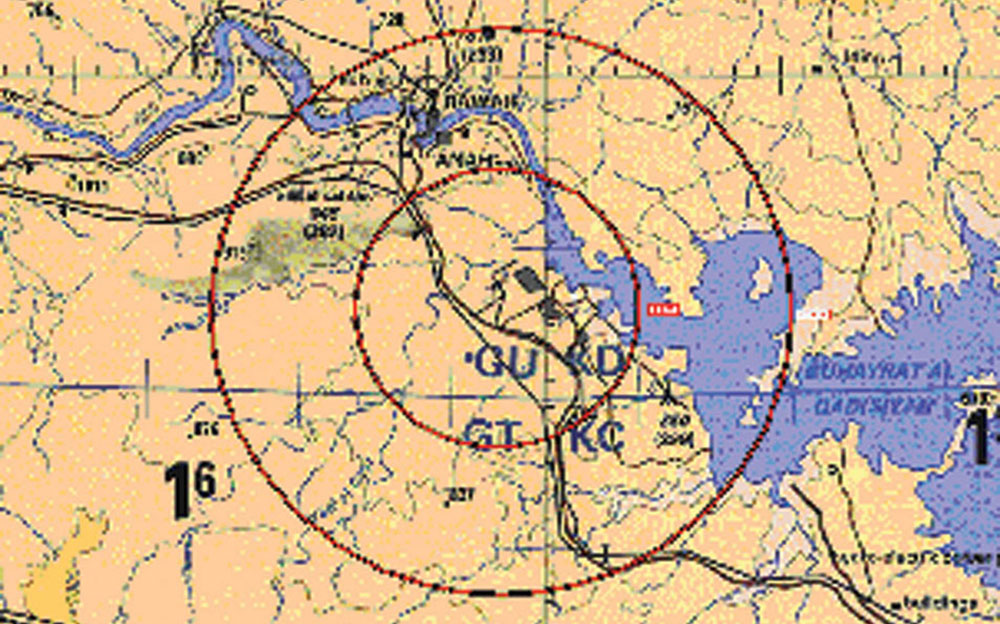

With the infiltration phase completed, the ground assault force methodically searched Objective Beaver for evidence of a chemical weapons program. For protection, two concentric rings of close air support surrounded the objective area, and the Ranger blocking positions secured main avenues of approach to the site. The AH-6 gunship pilots combed the area at a slightly higher altitude than the MH-6s, responding to Ranger calls for fire and engaging observed combatants. The gunships had destroyed most of the initial resistance, which consisted of small armed groups that had quickly formed across the street from the landing zones. After the main force infiltrated, the MH-6 pilots were free to maneuver over the target and engage enemy combatants. CW3 Moffit spotted two Iraqi gunmen running from a driveway, each closely dragging a woman for protection. As CW4 Bursa positioned his sniper closer and lower, one gunman lost his grip on the woman, and the sniper immediately killed him. The second gunman backed into a concrete building and held the woman tightly. Bursa decided that it was more prudent to return to the target and reluctantly disengaged. In the other MH-6, CW4 Ellis spotted a vehicle racing toward a Ranger blocking position. The Rangers unleashed a storm of heavy weapons fire, but the driver kept going. As the vehicle approached the second Ranger position, machine gun fire stopped the vehicle and two armed men ran for cover. The Rangers killed one instantly. The second gunman ran down an alley out of their sight, but well within range of a sniper’s bullet from Ellis’s aircraft; the man was dead within seconds.12

Patrolling an outer ring, the DAP pilots focused on preventing any reinforcement of the target, primarily looking for vehicular movement towards the research facility along the main north-south road through the town. The rules of engagement required that a warning shot be given to stop vehicles. If the vehicle proceeded, then it presented a hostile intent and could be attacked. During CW4 Brady’s initial circuit around the objective area, a Toyota Hilux truck approached the intersection leading to the objective. Brady fired a short burst from his chain gun, but the vehicle continued. On the second pass, the driver stopped and shut off his lights as the DAPs approached. Once the flight turned outbound, the driver started moving again. On the next turn, both Brady and Hamilton fired 30 millimeter rounds into the vehicle, destroying it. The occupants ran for cover into a nearby building, and were never seen again. A short time later, another vehicle rapidly approached the same intersection. The two occupants stopped when given a warning shot, and dove into a ditch, only to fire at the helicopter on the next pass. Flying with Brady in the lead DAP, CW3 Walter Florenson (pseudonym) watched tracer fire blaze past his chin bubble. Brady swiftly banked the DAP into a firing position and released a barrage of bullets at the source. One gunman died in place, and the other retreated into a building, safe for another day. So it went until the call for exfiltration came.13

After nearly forty-five minutes on the objective, the assault team called for exfiltration. CW3 John Nailor, the second Chinook flight leader, anticipated implementing the contingency exfiltration plan while in a holding pattern at the release point. His flight of two Echoes carried the immediate reaction force and the CSAR element. By pushing the helicopter to its physical and operational limits, Nailor calculated that two Chinooks could transport the assault force. Wasting little time, the Chinooks cycled in and out of the objective with all the assaulters. The Black Hawk pilots, having departed the DLS earlier, extracted the Rangers from their respective landing zones. Coming into their landing zones, the Black Hawk pilots took note of the carnage the Rangers and their fellow Night Stalkers had wrought; dead Iraqis appeared to be everywhere. Some pilots repositioned in order not to land on the dead bodies. The Rangers boarded, and Hoyt led his flight to Roadrunner, with the Little Birds and DAPs following in trail. The objective was behind them, but the operation still held surprises for the fatigued Night Stalkers.14

As the helicopter fleet landed at the DLS, the entire area became obscured by dust clouds churned up by the prop wash. Crew members and pilots could not see past the probes of the helicopters, and most stayed where they had landed. Low on fuel, Nailor led a flight of Chinooks and DAPs to the aerial refueling track, joining en route to avoid a collision during takeoff. The tanker met Nailor’s flight and all went well until the DAPs moved into position for refuel. While maneuvering into refuelling position, Brady noticed that his fuel burn rate was higher than normal. Spotlighting the helicopter’s probe, he saw fuel leaking. He decided to refuel anyway, and connected with the hose of the tanker. The alternative was to end up a CSAR mission. The gamble paid off as the leaking stopped when Brady disconnected after refuel. Back at the DLS, the Kilo pilots waited for the tanker to land so they could refuel with help from the FARP crew. That turned out to be a prudent decision, because a Kilo crewmember noticed that his own refueling probe had also been struck by a bullet and was leaking. The crewman affixed a temporary patch and refueled. The entire helicopter fleet finally reached the FSB two and a half hours later.15

The raid on the Al Qadisiyah Research Center proved to be a greater risk to man and machine than had been expected. Two Chinooks and three Black Hawks sustained damage from armor piercing rounds, not the type of munitions one would expect at a research center. In spite of the stiff resistance, SOF’s realistic training in peacetime enabled them to complete the mission. The Night Stalkers executed several contingency plans without a disruption of the mission; Rangers and SOAR attack pilots kept the enemy from reinforcing the objective; and two men’s lives were saved by combat lifesaver-qualified crewmembers. Once again, SOF proved their worth by completing an important mission ideally suited to their unique capabilities.