DOWNLOAD

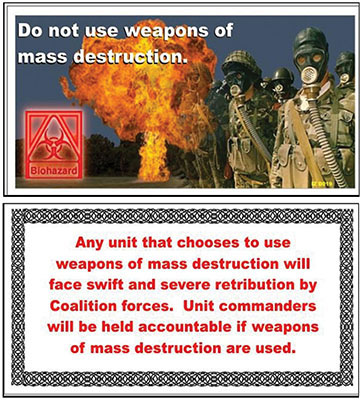

Psychological Operations (PSYOP) is potentially one of the most powerful tools the military possesses. Conveyed to foreign audiences in a variety of ways, PSYOP messages support U.S. goals and objectives, whether they be offensive, defensive, or peaceful in nature. Properly applied, PSYOP can wear down an enemy’s resolve to fight, diffuse a tense standoff between would-be attackers and U.S. troops, and ensure fair distribution of humanitarian aid. PSYOP activities leading up to and during Operation IRAQI FREEDOM (OIF) used a number of means to deliver coalition messages to the Iraqi military and the civilian population. Two of the more notable methods of distribution were radio and television broadcasts of coalition programming and leaflet drops.

A large part of the PSYOP in OIF activities consisted of media broadcasts directed at the Iraqi people, both military and civilian. Both the Special Operations Media System-Broadcast (SOMS-B) and the EC-130E Commando Solo proved to be capable and valuable broadcast platforms. Working independently and in concert, the SOMS-B and Commando Solo teams successfully delivered their messages to critical audiences throughout Iraq.

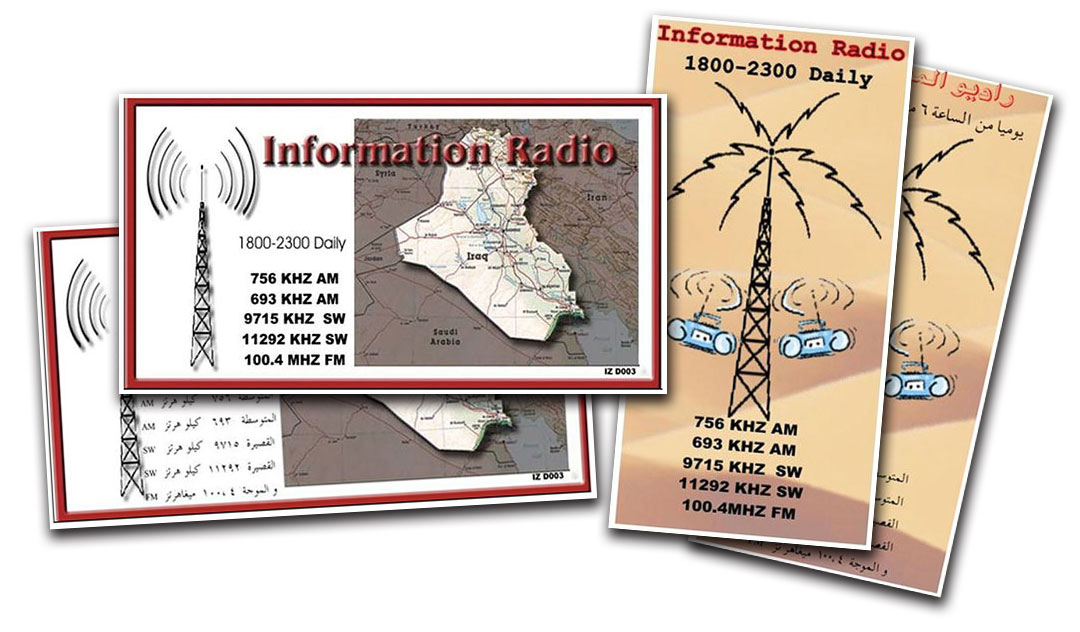

The SOMS-B consists of two primary subsystems: the Mobile Radio Broadcast System (MRBS) and the Mobile Television Broadcast System (MTBS). Between the two subsystems, the SOMS-B can broadcast via AM, FM, and short wave radio, as well as television. The Joint PSYOP Task Force made up of elements of the 4th PSYOP Group initially set up a SOMS-B in Kuwait in mid-December 2002 and immediately began to broadcast messages throughout southern Iraq. In the beginning the SOMS-B unit broadcast radio messages for five hours a day, but by February transmission times had extended to eighteen hours every day. When combat operations began on 19 March, the SOMS-B broadcasts provided PSYOP support twenty-four hours a day.1

CPT Robert Curris, the commander of the SOMS-B element, requested additional SOMS-B equipment be brought into theater to supplement his unit’s capability. The new unit, a SOMS-B “light” comprised of just the MRBS, accompanied 3rd Infantry Division north to Baghdad. A third SOMS-B arrived from Romania and began broadcasting from Baghdad International Airport (BIAP). With three systems established between Kuwait and Baghdad, combined with daily Commando Solo broadcasts, almost all of Iraq had access to coalition messages via AM, FM and short wave radio.2

The EC-130E Commando Solo aircraft also played a significant role in broadcasting PSYOP messages. Based in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, the Air Force National Guard’s 193rd Special Operations Wing (SOW) is home to the Commando Solo Aircraft and is tasked with providing aerial transmission of PSYOP messages. The Commando Solo platform can broadcast on the commercial AM/FM and short wave radio bands, VHF/UHF television bands, and military VHF/HF/FM frequencies. Having such comprehensive broadcast capabilities in an aircraft enables the 193rd SOW to support military operations worldwide. As the 193rd SOW is the only unit in the Air Force dedicated to this mission, the Commando Solo crews truly do support global operations, and OIF was no exception.3

A detachment of the 193rd SOW, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Geral Otterbein, arrived in the region on 24 March 2003. The detachment consisted of one EC-130E Commando Solo aircraft, two full EC-130E crews of eleven people each, two support C-130s, and associated staff and support personnel. The Commando Solo detachment brought into theater aerial television transmission, AM/FM/HF radio broadcast, and “net intrusion” (military radio net interruption) capability, all of which allowed wider distribution of PSYOP messages.4

The 193rd SOW detachment was fully operational within forty-eight hours of arriving in theater. Under the tactical control of the Joint PSYOP Task Force (JPOTF) in Qatar, the detachment was given areas to target with the television and radio broadcast tapes that the Commando Solo crews received from the 4th PSYOP Group at Fort Bragg. The Army PSYOP liaison attached to the 193rd SOW, Sergeant (SGT) Dennis Relyea, reviewed the taskings and planned and coordinated all broadcast plans with the detachment’s Operations Officer, LTC Kevin Satow.5

Flight planning proved to be a delicate undertaking. The 193rd SOW initially flew missions outside Iraqi airspace, but still close enough that it could transmit to the majority of western Iraq. The JPOTF urged LTC Otterbein to broadcast to cities north of the Euphrates River, which would require flying over western Iraq, making the aircraft vulnerable to attack. The EC-130E mission called for it to orbit in “tracks” for long periods of time. The EC-130E is also an extraordinarily heavy aircraft, lacking the maneuverability necessary to react quickly to threats. While transmitting, the aircraft also normally trails a four hundred-foot long wire antenna that is invisible at night, which further reduces maneuverability. Major (Maj) David Redclay, an aircraft commander in the 193rd, explained that with the antenna deployed, the aircraft “can make one reaction from a threat. If there’s a follow on, second one, you’re going to the guillotine the aircraft or cut the wire and then our AM broadcasts are done.” Further risk lay in the fact that the aircraft’s APR-47 missile warning system was inoperative. In short, the 193rd SOW would not conduct flights over hostile areas until the Joint Special Operations Air Detachment (JSOAD) and 193rd SOW detachment intelligence officers decided the threat was at an acceptable level.6