DOWNLOAD

Camp Mackall began its ongoing life as a training center for the U.S. Army’s elite in 1943, amidst the excitement and turmoil of World War II. Carved from the pine forests of the North Carolina Sandhills, just miles away from bustling Fort Bragg, the spacious installation was the ideal place for training airborne and glider infantrymen. Built in a record six months, Camp Mackall boasted a mind-boggling array of facilities: more than seventeen hundred buildings, sixty-five miles of paved road, sixteen post exchanges, twelve chapels, two large guest houses, five movie theaters, a twelve hundred-bed hospital, and enough barracks to house twenty-five thousand troops.

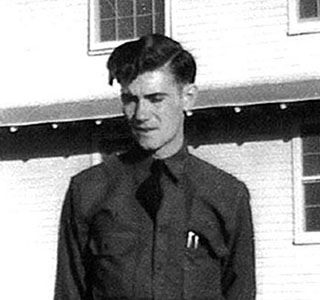

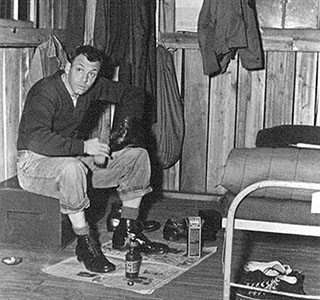

While initial parachute training took place at Fort Benning, Camp Mackall was where newly minted paratroopers came for advanced parachute infantry training and airborne maneuvers. The 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions trained at Fort Bragg, and the 11th, 13th, and 17th Airborne divisions trained at Mackall, all preparing for battle in the Pacific and Europe. The famous “Triple Nickel” 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion, the first all-black paratroop unit, also trained at Camp Mackall before they deployed west in May 1945 as “smoke jumpers,” fighting forest fires started by balloon-borne Japanese incendiary bombs.

When peace came in Europe and then the Pacific, Camp Mackall’s heyday as an airborne training center came to an end. The Airborne Center and support troops transferred to Fort Bragg in November 1945, and the camp was placed on inactive status in December. Because the camp had been built according to contingency standards, it would cost some $56 million to make the camp suitable for a permanent base. By mid-1946, Camp Mackall had transitioned from being one of the largest military installations in the United States to serving as a sub-camp of Fort Bragg. By the late 1950s, Camp Mackall was being used for selection and training of U.S. Special Forces soldiers, a role it fulfills to this day.