DOWNLOAD

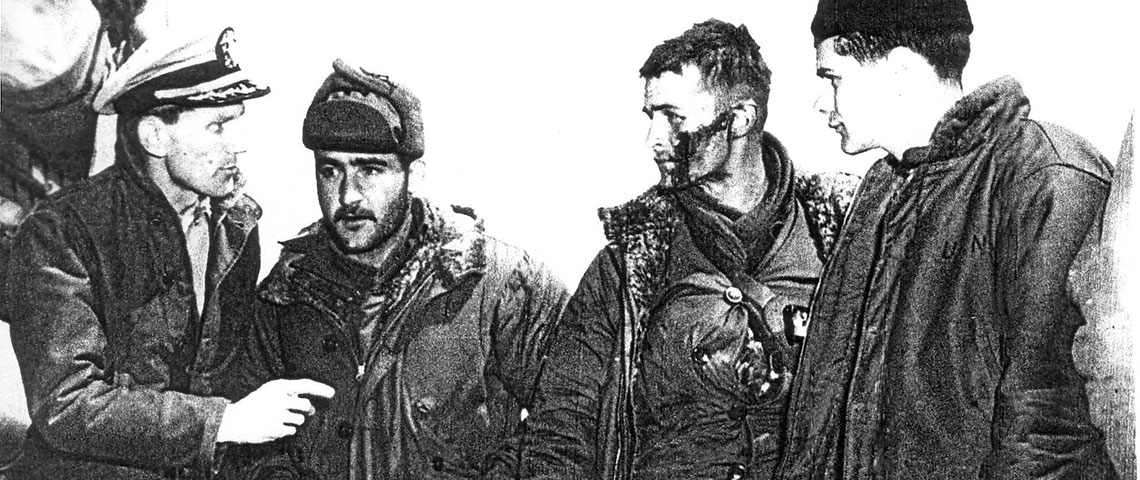

In the world of special operations, combat search and rescue of troops requiring evacuation from behind enemy lines is one of the primary missions given to helicopter crews. The rescue of three Americans by Navy helicopters from behind North Korean lines in March 1951 is one of the earliest combat search and rescue missions on record. The rescue of Virginia 1 ended a star-crossed operation with the successful evacuation of three operatives, unfortunately at the expense of one helicopter and the internment of two Americans. Like the mission itself, the rescue was one of great bravery in the face of extreme odds.

One of the primary objectives of the Eighth Army staff in late 1950 was the interdiction of the enemy’s southern supply lines. Two major rail networks supplied the Communist forces in the field: one ran from China through P’yongyang and down to Seoul, while the other ran from the Russian port of Vladivostok south along the east coast to the port of Wonsan. At Wonsan, where the rail lines divided into the main Ch’orwan–Seoul line and had a secondary spur running from Ch’orwan to Ch’unch’on-Wonju. Movement along these rail lines needed to be stopped.

Aerial bombardment by United Nations (UN) aircraft took a significant toll on the movement of supplies from China on the P’yongyang–Seoul route, where long stretches of flat, open terrain provided ample opportunity for the destruction of the rail lines and roads. By January of 1951, only half the supplies and seven of ten replacements that left China were reaching the armies south of Seoul.1 Air interdiction of the eastern route was markedly less successful.

On the Wonsan to Wonju corridor, steep, angular mountains and deep narrow valleys protected the rail and road networks from direct assault by the UN aircraft. North Korean and Chinese Army engineers were typically able to rapidly repair the small sections the aircraft could access, and the flow of supplies was barely interrupted. More than 70 percent of supplies and nine out of ten replacements were able to move down the east coast routes to reinforce the frontline forces.2 The Eighth Army planners looked for other vulnerable spots to try to slow down the flow of materials to the enemy.

The rail routes out of Wonsan ran through numerous tunnels as the rail line weaved among the mountains on its way south. Several of these tunnels were within striking distance of the coast. An early attempt at attacking the tunnels occurred when Republic of Korea (ROK) Marines accompanied by U.S. Navy underwater demolition team personnel landed south of Wonsan and detonated charges in a tunnel edging the coast. The team returned intact with two prisoners, but within two days a temporary rail line was in place, bypassing the blocked tunnel.3 A more remote, less easily repaired tunnel was the answer, and the tunnel at Hyon-ni, thirty miles inland, met the criteria. The mission to drop the tunnel fell to the Eighth Army G-3 Miscellaneous Division, where Colonel (COL) John H. McGee was in charge of training partisan forces for operations behind the North Korean lines.

An unexpected by-product of the North Korean and Chinese drive south following the Chinese entry into the war was the large number of anticommunist refugees that fled before the advancing armies. Despite living under Communist rule since 1945, many thousands of North Koreans took advantage of the dislocation and chaos of the war to make their way south. This large pool of manpower enabled the UN Far East Command to expand its ability to conduct clandestine operations behind enemy lines. The program grew from one of small, localized incursions to a comprehensive campaign of sabotage and raids throughout the Korean peninsula.

By July 1951, after six months of superhuman effort, McGee established an organization that ultimately employed several thousand partisans on both coasts. The 8086th Army Unit (8086th AU) fielded partisan forces on both coasts. Leopard Base, which supported fifteen partisan units called “Donkeys,” was located on the western islands north of In’chon. The CIA-supported Task Force Kirkland operated offshore on the East Coast, near Wonsan. A third element, Baker Section, was responsible for training airborne partisan forces for sabotage behind the enemy lines, and it was to this element that McGee looked to support the sabotage of Hyon-ni Tunnel. Unfortunately, time for proper preparation for this complex mission did not exist.

On 25 January 1951, the Eighth Army initiated Operation THUNDERBOLT—a strong reconnaissance in force against the Chinese XIII Army Group arrayed in front of the UN forces south of Seoul. The operation was designed to push north as far as the Han River.4 By 3 February, the UN forces had progressed up to the south bank of the Han, where the advance halted short of trying to take the capital city of Seoul. A second phase pushed the advance in the eastern sector further north by mid-February. General Ridgway followed up the success of THUNDERBOLT with Operation KILLER, a methodical advance across a sixty-mile wide sector of the front east of Seoul between Yangp’yong and Ch’angdong-ni. This operation was designed to inflict the maximum number of casualties on the enemy.5 These operations depended on the Allies slowing the flow of supplies and reinforcements to the Communist forces and necessitated the immediate execution of the plan to sabotage Hyon-ni Tunnel. The plan went by the name Virginia 1.

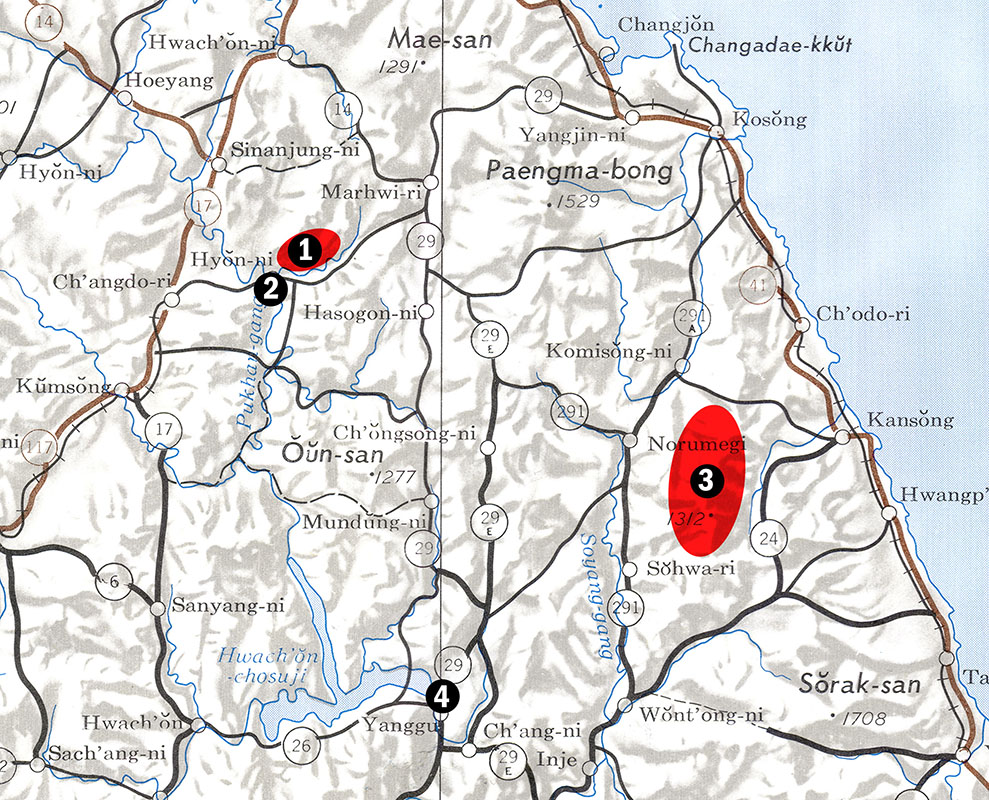

2: Location of the Hyonni Railroad Tunnel;

3: Rescue of Miles, Baker, and Pucel along the ridge 30 March 1951;

4: Watson and Thornton captured north of Yanggu: Thornton 8 April 1951 Watson 9 April 1951.

The concept of Virginia 1 began with an airborne insertion of a team of American and ROK soldiers into the mountains south of Hyon-ni. The team would move up the ridgelines to a position above the railroad tunnel and, after a reconnaissance, set charges at each end of the tunnel, closing it to traffic from both ends. The exit route took the team thirty miles southeast towards the coast. The evacuation plan called for a pickup on the coast by boat. The alternative plan for pickup, code-named Dallas, called for aerial evacuation by Navy helicopters stationed on ships off the coast of Wonsan. The entire mission was supposed to be completed in thirty-six hours.

Colonel McGee realized that the partisan forces in training in Baker Section would not be ready to successfully execute a mission like the sabotage of the railroad tunnel. He turned to the ROK Army Officer Candidate School for volunteers with combat experience for his plan. Forty-four volunteers were selected and the group was divided in half for training in sabotage and airborne operations. The Eighth Army G-3 selected 15 March 1951 as the execution date for the mission, leaving five weeks for Baker section to prepare the Koreans.6

Airborne training was conducted at K-3 Air Base in Kijaing on the outskirts of Pusan. McGee’s Miscellaneous Section took over the former Eighth Army Ranger training facility and turned it into a site for airborne training. Former Ranger training cadres were retained as instructors, as all were airborne qualified. The training for the section sent to K-3 ended with the first training jump. The pilot miscalculated his approach and the drop zone control party underestimated the force of the winds. As a result, the jumpers landed among frozen rice paddies several hundred yards off the temporary airstrip that was the drop zone. As strong wind gusts blew the jumpers across the uneven ground, eleven suffered broken bones and nine more were seriously bruised. After this incident, this section’s training was cancelled and twenty of the twenty-two men ultimately returned to the ROK Army officer candidate academy. Two remained and were later sent on other clandestine missions.7

After the debacle with the airborne training, it was determined that the second section would receive four weeks of intensive training in sabotage and demolitions at the center in Pusan and not conduct any airborne training. The director of the sabotage school was British Special Air Service Captain Ellery Anderson, a former Special Operations Executive operative in World War II. During that war, airborne training for partisans was reduced to a day of ground training and then the actual mission jump onto the objective. Anderson adopted a similar program for the ROK volunteers for Virginia 1.8