NOTE

* Pseudonyms have been used for all military personnel with a rank lower than lieutenant colonel.

DOWNLOAD

In the battle area of the western desert of Iraq, the 5th SFG looked for ways to help shape the battlefield for conventional forces attacking toward Baghdad. Once the ground war began, Central Command’s plan was to keep the Iraqis off balance by hitting them hard and fast with armored and mechanized ground forces. Ahead of the conventional forces juggernaut, the Special Forces operators planned to support the maneuver forces with ODAs conducting deep reconnaissance of strategically important areas and making contact with anti-Saddam resistance groups. The challenge for SOF planners was how to insert the ODAs rapidly and efficiently deep into Iraq using a limited number of aircraft in order to support Central Command’s plan.1

The SOF planners knew that Air Force MC-130 aircraft were required for any deep infiltration mission. The immediate problem was locating a suitable desert landing strip that met both the Air Force landing criteria and the Army’s mission requirements. MC-130 Combat Talons were capable of landing on unimproved runways, but they needed a stretch of reasonably flat, firm, and open ground at least 3,500 feet long and 60 feet wide. The Air Force also insisted that runway conditions be validated on the ground by trained and qualified Air Force controllers. The Army’s mission required that the infiltration be accomplished well before the conventional forces began their attack, that the landing strip be near the Karbala-Najaf area, and that the infiltration site be away from known enemy concentrations.2

The mission to find such a place was given to Major Boyd Sinclair* and ODB 570. He was told to develop a primary and an alternate plan to establish an advanced operating base at a desert landing strip deep within Iraq. The desert landing strip would be used to infiltrate ODAs and other SOF teams for missions in support of conventional forces. His detachment needed to be prepared to receive the first ODAs within twenty-four hours of verification, and continue to operate the landing strip for up to forty-eight hours. When the last teams were on the ground, Sinclair’s base would exfiltrate on the last aircraft. The forces available for the operation included Sinclair’s ODB 570 under its operational designation of AOB 570, ODA 574, and four Air Force combat controllers from the 23rd Special Tactics Squadron (STS). The detachment was on a tight time schedule—all mission preparations had to be completed in anticipation of launching as early as the night of 17 March.3

AOB 570 was fortunate to have a highly qualified and experienced Air Force combat control team from the 23rd STS assisting in the planning for the operation. Three members of the team were veterans of Afghanistan with first-hand experience operating desert landing strips. The savvy controllers cautioned that simple dirt landing strips tend to become badly rutted after only a few landings, and the mission profile for this operation called for multiple aircraft and multiple sorties.4

The experienced judgment of the Air Force controllers caused the team to look for existing hard surface landing strips that might be useable. Unfortunately, the intensive bombing campaigns of Operation DESERT STORM and the post-Gulf War enforcement measures in the Southern No-Fly Zone left most of the existing flight strips in Iraq severely cratered or otherwise damaged. However, after a careful analysis of existing imagery and some additional low-level, high-quality photos provided by British Tornado reconnaissance aircraft, the team felt that the abandoned Iraqi fighter base at Wadi al Khirr might meet the mission needs.5

Wadi al Khirr Airfield, located 240 kilometers southwest of Baghdad, was built in the 1980s by Yugoslav contractors and had a single 9,700-foot long runway. At one time, the air base had twelve hardened aircraft shelters, but bombings during DESERT STORM had reduced them to piles of rubble.6

The 23rd STS reasoned that between the main runway and a parallel taxiway, a suitable landing strip could be pieced together. For the Special Forces, Wadi al Khirr was reasonably close to the key Karbala-Najaf area, and the only known enemy facilities in the vicinity of the airfield were Iraqi border posts nine miles away.7

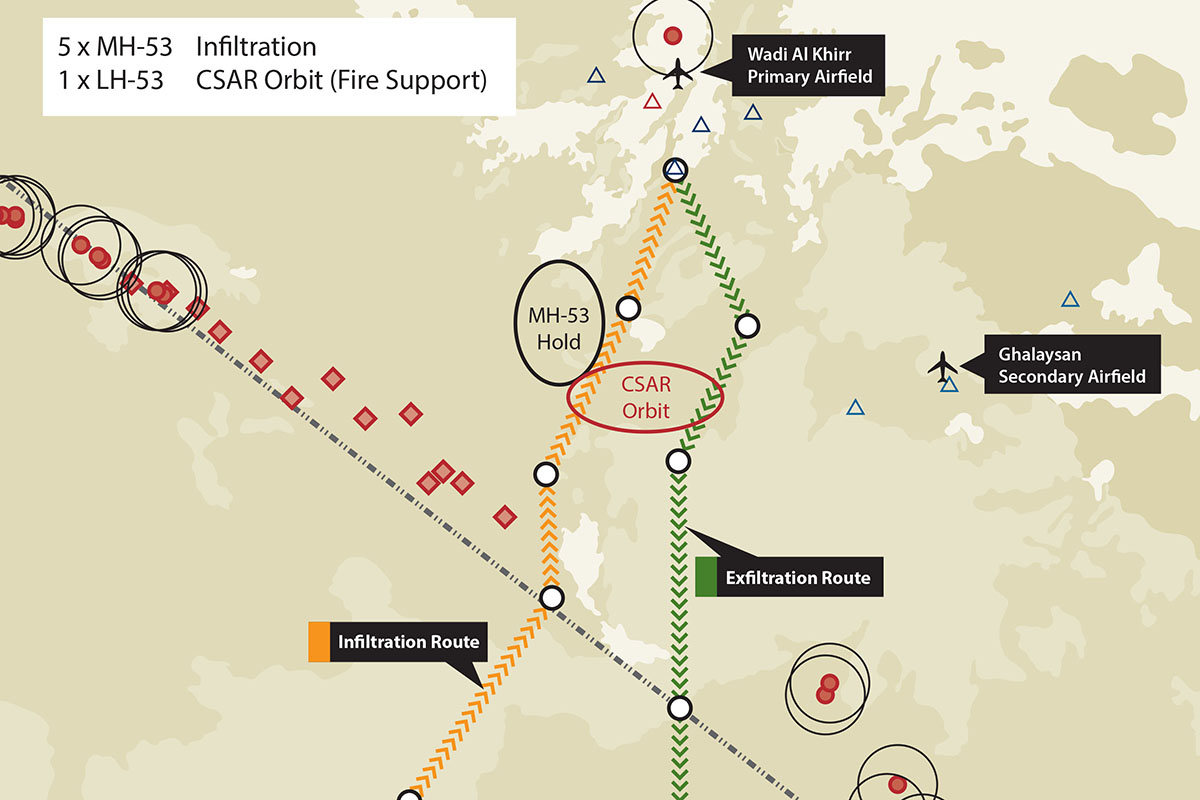

Once it had selected a primary site for the desert landing strip, the AOB had to plan and coordinate the myriad of details that make all the pieces of a joint operation fit together. Deep penetration SOF aircraft were limited—in the opening days of the war, competition for air assets was keen. Thus, getting the AOB to Wadi al Khirr was one of the first issues to be addressed. Both ODA 574 and the 23rd STS team were high altitude-low opening qualified, which made parachute entry an option offering a degree of economy in air assets. However, lessons learned from DESERT STORM made a convincing case that in a desert environment, dismounted Special Forces teams were at a distinct disadvantage if compromised. The planners decided to use Air Force MH-53J helicopters to infiltrate the twenty-six AOB 570 soldiers and airmen, as well as five nonstandard vehicles (NSVs) and four all-terrain vehicles (ATVs).8