NOTE

* Pseudonyms have been used for all military personnel with a rank lower than lieutenant colonel.

A large part of the work in Afghanistan centered on Civil Affairs (CA) teams working in remote locations and hazardous conditions. This article is a “snapshot” of one location—Gardez, Afghanistan—and some of the situations in which CA teams found themselves while trying to accomplish their missions. The incidents and conditions discussed in this article occurred in 2002, but are representative of the difficulties still faced by CA teams performing the ongoing mission in Afghanistan, Operation ENDURING FREEDOM. The majority of long-term CA support for OEF has come from a variety of U.S. Army Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations Command units, building on the initial missions undertaken and fulfilled by the 96th Civil Affairs Battalion (CAB).

While the U.S. Army Special Forces and the Coalition supported the Northern Alliance fight against the Taliban and al-Qaeda, CA units moved into the war-devastated country to begin the rebuilding process. By early November 2001, the 96th CAB deployed two CA companies (C and D companies) to the theater. The companies supported the two special operations task forces (Dagger and Kabar) fighting the Taliban and al-Qaeda forces in Afghanistan.

The 96th CAB teams began to fill the humanitarian aid void in parts of Afghanistan at war. It was much like inserting critical pieces into a large, complex jigsaw puzzle. Within days of arrival, the four-man Civil Affairs Team–As (CAT-As) (twelve teams, six per company) were conducting humanitarian assessments throughout the country. The initial data collected helped the Coalition establish priorities for aid and assistance. In order to accomplish their missions, the CA soldiers established what became known as Coalition Humanitarian Liaison Cells (CHLCs) throughout the country, operating primarily with Special Forces teams.1

As the 96th CAB established the CHLCs in key coordination hubs throughout Afghanistan, a new CA headquarters, the Coalition Joint Civil Military Operations Task Force (CJCMOTF), was established. By December 2001, the advance party of the CJCMOTF had arrived in Kabul to begin operations. While the 96th CAB’s CHLCs conducted operations, a larger Army Reserve force was mobilizing at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. On 18 February 2002, the first echelon (thirty-eight soldiers) of the 489th CAB (Knoxville, Tennessee) arrived at Bagram Air Base to replace the 96th CAB. In the weeks that followed, the rest of the battalion arrived in Afghanistan. The 489th CAB was augmented with thirty-one soldiers from the 401st CAB (Webster, New York) in order to expand operations and provide support to the U.S. Army units operating throughout the country. The 489th CAB “fell in on” the established Civil Military Operations Centers (CMOC) in Bagram and Karshi-Karnabad, Uzbekistan (the base commonly referred to as “K2”), to provide command and control as well as logistics support to ten CHLCs as they deployed to replace the 96th CAB teams throughout the country.2

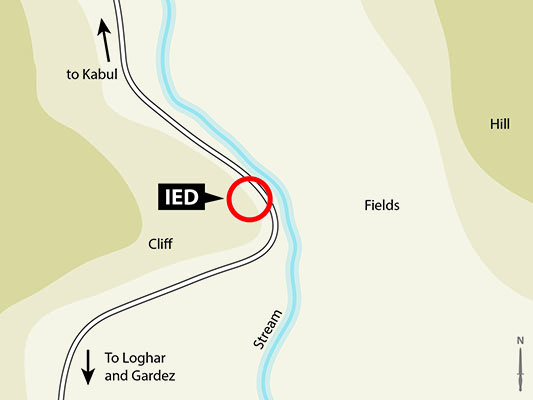

Gardez, the capital of Paktia province, is important because of its strategic location. It is a major crossroads for the north–south and east–west road system. The province sits astride the major routes in and out of eastern Afghanistan. Nestled along the Pakistan border, the area is easily accessible to al-Qaeda and Taliban forces who regularly slip from the frontier region into Afghanistan. Although located only sixty miles south of Kabul, it is separated from the capital by a major mountain range. The sixty miles that would take an hour and a half to drive in most Western countries, would take convoys anywhere from two and a half to six hours, if the convoy could get through at all. The two-lane road snaked through a mountain pass that rose from 6,000 to 9,000 feet above sea level before dropping down to the valley floor. Gardez sits at 7,053 feet.3 The task was daunting because the CHLC had to cover an area the size of South Carolina with three to five personnel on a team.

The entire Paktia province, including Gardez, was a contested area. On the outskirts of town, the Special Forces had established a forward operating base during Operation ANACONDA and the Shah-e-Khot Valley fighting in 2002. It was home to various Special Forces operational detachments alpha (ODAs) from January 2002 to August 2002. An ODA from 5th Special Forces Group and ODAs 394 and 395 (from 3rd SFG) operated from the Gardez compound in the spring and summer of 2002. They were replaced by an ODA from 20th SFG in the summer of 2002. Captain Ken Harrison* moved his CAT-A 56 (Company E, 96th CAB) to Gardez on 7 February 2002, established a CHLC, and conducted assessments.4

After coordinating humanitarian deliveries of food and blankets to villages in the Shah-e-Khot Valley following Operation ANACONDA, the team moved back to the Special Forces compound. During the deliberate assessment of Gardez in support of Advanced Operating Base 390, Harrison and his team discovered that political infighting between two warlords had divided the city. With weapons pointed against them everywhere, humanitarian assistance to the city was impossible. Gardez was regarded as a “no win” situation. Protecting the limited CA assets, the team moved to Khowst on 29 March 2002 to conduct operations.5 This caused a gap in the area’s CA coverage, although the Special Forces ODAs in Gardez had conducted some civic action projects as part of their missions. The absence of a CHLC and dedicated CA assets sent the message to the competing factions in Gardez: cooperate with the Coalition or the aid coming into Afghanistan would bypass Gardez and be sent to more friendly areas.6

CJCMOTF planners continually reassessed the security situation throughout Afghanistan. In June 2002, additional CA assets from the 360th Civil Affairs Brigade arrived in Kabul. This freed up the 489th CAB soldiers for duties outside of the capital. One of the CJCMOTF priorities was to set up a CHLC in Gardez. This posed a challenge. There was no CAT-A designated for Gardez. To fill the gap, soldiers from the 489th CAB’s Public Health Team were formed into an ad hoc CHLC under Major James Collins*.7

The newly formed CAT-A/CHLC 13 moved by ground convoy from Kabul to Gardez on 18 September 2002.8 Almost immediately, the CA team began providing support and humanitarian assistance throughout the province. The four-man team had a daunting task and CHLC 13 needed the cooperation and support from the population. To achieve this, it had to aggressively interact with the provincial governing officials.9

To accomplish its mission, the soldiers of CHLC 13 established two priorities: the first was to assess needs and propose Overseas Humanitarian, Disaster, and Civic Aid (OHDACA) projects with local input; the second, to work with the non-governmental organization/international organization (NGO/IO) community. This part was key. Accurate, up-to-date humanitarian assistance and security assessments of the area were needed to support NGO/IO return to Paktia Province. The CHLC assessed the towns of Gardez, Zormat, Mihlan, Dara, and some smaller villages in the Shah-e-Khot Valley. Based on the assessments, it prioritized eleven high impact OHDACA Projects to be started in the first thirty days and then the projects were submitted to the CJCMOTF. These included the construction of new schools, health clinics, and the drilling of water wells. Project selection and priorities were closely coordinated with Provincial Governor Dalili and the Paktia Province Departments of Education and Health to inculcate local participation.10

The CHLC was very aggressive. It had to quickly meet and coordinate with the few NGOs and IOs operating in Gardez and in the rest of the Paktia province. The CHLC office in the Special Forces compound often became the coordination center for local humanitarian assistance actions. There, CA soldiers provided the NGOs/IOs a daily province situation and threat briefing to strengthen their commitments.

Getting the NGO/IO to be more proactive in Paktia province became a priority for CHLC 13. In October 2002, the CHLC briefed the humanitarian assistance needs and current status of Paktia Province at a NGO/IO meeting in the Kabul CJCMOTF. The briefing fostered more meetings with high-level United Nations officials who were keenly interested in returning to Gardez and Paktia Province to implement development programs. Increased NGO/IO activity was designed to achieve a fundamental CA goal—to work the CHLC out of a job.