From Veritas, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2006

DOWNLOAD

The signing of the unconditional surrender of the German armed forces on 7 May 1945 divided the country of Germany into four zones of occupation by American, British, French, and Russian armed forces. These zones of occupation represented the final troop dispositions. As a result, the city of Berlin was entirely surrounded by territory occupied by Soviet forces. In 1949 this became the German Democratic Republic or East Germany.

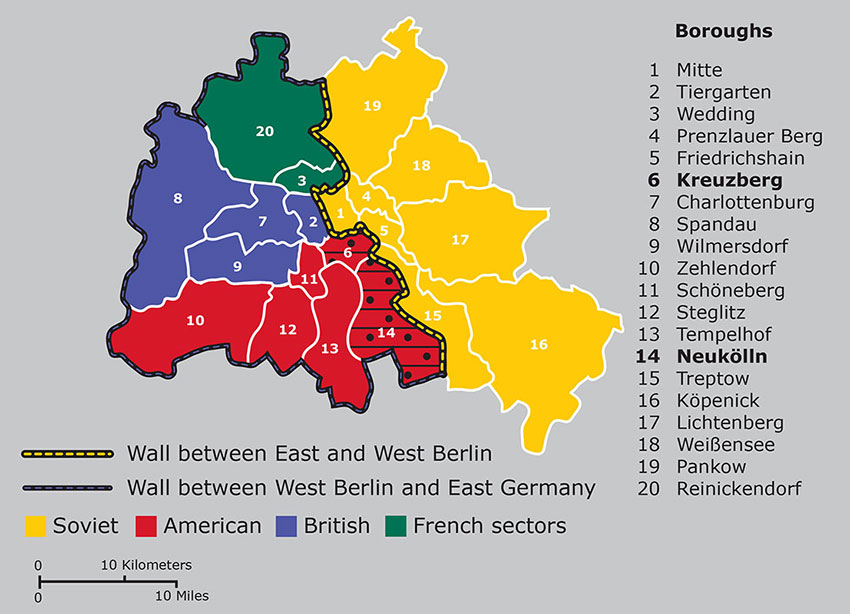

The city of Berlin was partitioned into East and West Berlin. East Berlin was solely occupied by the Soviet Union while West Berlin was divided among the United States, France, and England. Since there had been no agreement among the occupying powers concerning land and water routes into Berlin from West Germany, the Soviets took every advantage to make movements in and out of West Berlin by these means as difficult as possible. Conversely, air access had been regulated and three corridors were established from Hamburg, Hannover, and Frankfurt allowing access to the airports at Tegel (French sector), Tempelhof (American sector), and Gatow (British sector). These air corridors saved West Berlin from ruin during the Soviet blockade of the city in the winter of 1948–1949.

The final Soviet attempt to control access to Berlin occurred in 1961 when West Berlin was surrounded, first with temporary fortifications, and then by a concrete wall entirely around West Berlin. In the city, East Berlin building windows and doors that faced the western sectors were bricked-up. The only openings in the wall were two guarded crossing points at Checkpoint Charlie and Invalidenstrasse. The rationale for this action by the East Berlin government was to prevent military aggression and political interference from West Germany. This situation lasted until 9 November 1989 when private citizens took it upon themselves to begin demolishing the wall. No government interference came from either the West or the East Berlin authorities. Final sections of the Wall were removed with the assistance of the East Germans and in 1990, East and West Germany were reunited as one nation.

Traffic into the city of Berlin via road, rail, and air corridors was tightly controlled. Crossing from East to West Berlin and from East to West Germany took place only at designated check points.

Soviet American British French sectors

The purpose of this article is to present a snapshot in time that highlights the training and operations of Detachment A, Berlin Brigade. It was experienced by me during my tour as Detachment Commander. I was the last commander of this unique, multi-missioned unit.

Detachment A was formed in 1956 with six operational ODAs and a staff element. It was assigned to the 6th Infantry Regiment in Berlin. Immediately upon the outbreak of general hostilities, or under certain conditions of localized war, the teams were to cross from West Berlin into East Germany and attack targets designated by the U.S. Commander of Berlin as vital in his fight for the city as well as priority targets established in the U.S. European Command’s (USEUCOM) Unconventional Warfare Plan. Priority targets were: rail lines; rail communication systems; military headquarters; telecommunications; petroleum, oil, and lubricant facilities; storage and supply points; and utilities and inland waterways, in that order. Upon mission completion, teams were to conduct follow-on operations as directed by the Commander, Support Operations Task Force Europe. At the end of 1961, the basic plan was unchanged, but in a revision dated 1 July 1959, the six ODAs were reorganized into five mission task groups with the actions of each more clearly defined. After completing the assigned demolition missions, the five groups would be under the control of the 10th Special Forces Group whose primary focus was Central Europe. Two of these five task groups were to be prepared to move to predesignated operational areas or to return to West Berlin for “stay behind” operations.1 With only a few modifications based on command relationship changes and the general threat in the European Theater of Operations, this concept of operations was the basis for the Detachment’s primary mission under the USEUCOM Operational Plan.

The Detachment had the secondary mission of coordinating and developing plans and conducting operations in support of the USEUCOM counter-terrorist Contingency Plan. This meant that an operator had to be proficient in unconventional warfare and special operations in an urban environment, as well as tactics, techniques, and procedures to neutralize or contain potential terrorist threats.

In the 1980s, the U.S. Army emphasis was on the sustainment and employment of heavy ground forces to fight and win land battles on the continent of Europe against the vast Soviet armies. Little to no emphasis or encouragement was given to individuals or organizations that proposed other ways to make contributions to the total Army effort. Such was the situation with the U.S. Army Special Forces. Officers who volunteered for Special Forces were frankly told that whatever career success they had enjoyed was over and that the Regular Army didn’t want them back in its ranks when their tour with SF was over. They had been “ruined” for any other type of duty. Likewise, many of the personnel who were afforded the opportunity for SF duty were those whose respective branch did not want them for developmental assignments. Fortunately, some talented officers volunteered, became SF qualified and made significant contributions not only to Special Forces, but to the Regular Army as well.

While attending the Infantry Officer Advanced Course at Fort Benning, Georgia, in 1980, I was notified that I had been accepted for SF training. Upon successful completion of the Special Forces Qualification Course, I was to report to the Defense Language Institute (DLI) in Monterey, California, for thirty-two weeks of basic German language training. In early April 1982, my fellow Q-course classmates at Monterey began receiving assignment instructions to the 1st Battalion, 10th Special Forces Group, located at Bad Toelz, Federal Republic of Germany. With DLI graduation two weeks away, I finally received my assignment to Detachment A, Berlin Brigade. Having no idea what this unit was, I began asking questions. No one at DLI could shed any light on Detachment A. One week later, I received a welcome letter from my sponsor, Captain Dennis Warriner, with instructions to bring all military uniforms and relax my grooming standards. He further explained that he could not say anything more about the unit except it had a classified mission. I would be met at the airport by the unit executive officer since Warriner would not be present in Berlin on the day I arrived.

With family in tow, I arrived in Berlin on Sunday, 6 June 1982, and was met at Tegel Airport by Major Kevin McGooey, the unit executive officer. My first impression was the number of heavily armed German Police patrolling the airport with submachine guns. I was told that this was to counter terrorist threats from elements of the Red Army Brigade, the active anti-American faction centered in the West Berlin Free University. The Red Army Brigade occasionally conducted anti-U.S. demonstrations. Many faction members were young men who fled West Germany’s Bundeswehr (Army) draft. I was assured that we would be safe since we would be living in government quarters with other U.S. soldiers and their families. The area was referred to as the “American Ghetto.”

The following morning I wore civilian clothes to the unit to begin in-processing at Detachment A. The old adage of “first impressions are lasting” could have never been more true. Upon arriving at Andrews Barracks in the Lichterfelde District of West Berlin, I was escorted to Section 2, Building 904. After entering through cipher-locked doors, I was greeted by the stares of several loosely groomed individuals in German civilian clothes. No introductions were made. This was normal. In-processing began in the S-1. At 1000 hours, I reported to the Detachment A Commander, Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Darrell W. Katz. LTC Katz briefly explained that this was an all-volunteer unit. I would become an ODA commander in approximately thirty days. If I didn’t want to be assigned now or any time later, all I had to do was to tell him. He would arrange a reassignment.

After assuring him that I wanted to stay, I finished my in-processing. Then I tried to learn as much as possible about the organization, its standing operating procedures, and its missions. Detachment A was organized somewhat like a standard SF battalion except it was company sized and supported six ODAs.

Each staff section (called the Forward Control or FC) was headed by a senior non-commissioned officer (NCO), except Operations which had a captain who had already commanded an ODA in the unit. The NCOs were all highly experienced, qualified SF soldiers who could accomplish a multitude of tasks. Regardless of the request, they provided a solution to facilitate mission accomplishment. Fortunately, these section chiefs provided unit personnel “hip-pocket” instructions based on their knowledge and experience. This reduced the learning curve for “newbies.”

After being briefed, I was able to read Operations Plan (OPLAN) 4304, the USEUCOM General War Plan and Contingency Plan (CONPLAN) 0300—the military counter-terrorist option within the USEUCOM area of responsibility. Included in OPLAN 4304 was the dependent evacuation plan in the event of general war. While we trained to execute the USEUCOM OPLAN 4304 and the CT CONPLAN, the dependent evacuation plan was rarely discussed and never exercised.

On 1 July 1982, LTC Katz assigned me to command Team One. This detachment had a bad reputation. They lacked the discipline necessary to accomplish assigned missions. I learned that my team sergeant would be a master sergeant presently assigned to the S-2 office. All this brought reality into sharp focus. This was my first SF assignment after the qualification course and the team sergeant had not previously worked with this team. Fortunately, the new team sergeant had been in the unit for some time, had good rapport with the Det A sergeant major and knew the team and its personalities. Needless to say, we introduced ourselves and immediately discussed what needed to be done to turn Team One around.

We began with several days at the firing range. This had a two-fold purpose: training me in Close Quarter Battle firing techniques for the counter-terrorism mission and enabling the new team sergeant and me to observe and evaluate each team member’s skill during stressful situations. It also allowed the team to teach me and become familiar with their new team leader. This give-and-take experience quickly paid dividends. Individuals started identifying as a part of a team and a “team personality” evolved.

![On 26 June 1963, President John F. Kennedy and West Berlin’s Mayor Willy Brandt visited Checkpoint Charlie. During his visit to the city, Kennedy made his famous declaration: “Ich bin ein Berliner. [I am a Berliner.]”](images/v2n3_detachment_a/wide/kennedy_in_berlin.jpg)

In early August 1982, LTC Katz told me that I was to be the Officer-in-Charge (OIC) of Det A personnel supporting U.S. Army VII Corps in Return of Forces to Germany (REFORGER) exercise CARBINE FORTRESS. It would be the first time that elements of Det A had participated in REFORGER. The Det A contingent consisted of Teams One and Five, selected radio operators, a master sergeant from the S-3 (operations section), and the Detachment communications van with three radio operators. Teams One and Five members were divided into three-man cells with one radio operator per cell and assigned sectors in the exercise area. We established a mini–forward operating base on the U.S. Army installation at Illesheim, Germany, using the communications van and operations section. The Det A mission was to collect human intelligence (HUMINT) for the VII Corps Intelligence Section (G-2).

The exercise was progressing smoothly until mid-September, when one of the HUMINT cells was compromised and the members arrested by the German police. They were suspected of being terrorists. A local Gasthaus (hotel) owner had overheard a conversation about “snatching a German Army general.” This led to their arrest. At the police station, I presented our credentials and they were verified by the VII Corps G-2. Instead of being released, the men spent the night in jail. The next morning, the VII Corps G-2 HUMINT officer and I reported to REFORGER headquarters. A Canadian brigadier general and an American major general were waiting. The Canadian general’s first comment was: “Who the hell are you and where the hell are you from?” I responded. He cleared the room of everyone except the American general, the VII Corps HUMINT officer, and me. After a ten-minute, one-sided, “Do you understand what has happened here?” conversation, I was told to send this cell back to Berlin. No response was necessary. We saluted and left posthaste. I assured the generals that it would be done as soon as possible. After I got them out of jail, the men were sent to Frankfurt where they boarded the Frankfurt–Berlin Duty Train the same day. We continued our mission.

I met with each of the remaining operational cells, explained the situation, and “cautioned them” about personal behavior during the exercise. All went well afterward. Typical of Special Forces, the men nicknamed the unlucky cell leader “Agent Orange.” And, the label stuck.

Overall, REFORGER 1982 was a very successful exercise. Lieutenant General William J. Livsey, Commander, VII Corps, lauded the Detachment performance as the “only HUMINT source that prepared the Corps to meet any potential aggressor force actions.”2 It was an invaluable experience to operate with conventional forces. Det A demonstrated that Special Forces were truly a force multiplier. Furthermore, the missions provided training and experience in support of our OPLAN 4304 wartime mission. The success of 1982 insured participation in REFORGER 1983.

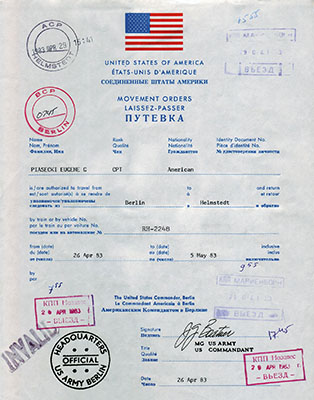

We redeployed to Berlin in late September 1982 on the Duty Train. It ran daily leaving Berlin and Frankfurt at 1900 hours. The train was available to all military personal assigned to Berlin, as well as dependents and guests. All that was required to ride was a reservation, a valid military identification card or passport, and a set of “Flag Orders.” Flag Orders, signed by the Commandant of Berlin, authorized travel on the Duty Train for members of the Allied garrison.

All passenger compartments had four bunks with communal lavatories at each end of the car. No alcoholic beverages were allowed on the train and the cars were patrolled by American Military Police. The train stopped at the border of West Berlin and East Germany and again at the border of East and West Germany to verify that the passengers listed on the train manifest were aboard and to ensure no one tried to exfiltrate or infiltrate illegally. There was also an additional train to Bremerhaven to ship and receive private automobiles from the United States. The same manifest checks were done for this train. The Military Police specifically monitored Det A members more closely than the other passengers.

After returning to Berlin, I discovered that my team sergeant had been replaced by Master Sergeant Howard Fedor, formerly on Team Three. He had served in the unit for six years and had a wealth of SF and Berlin experience. After our initial meeting, we decided to focus more on our area of operation in West Berlin. Each of the six ODAs was assigned two or three districts of Berlin without regard to which Western ally controlled them. Sector information was strictly limited to the specific team assignments. These assignments were made based on respective missions in support of OPLAN 4304. Team One had the Neukölln and Kreuzberg sectors. Of all the sectors in Berlin, these were probably the most diverse. Kreuzberg was the home of the “squatters,” young men living in dilapidated, condemned buildings to avoid the Bundeswehr draft. Neukölln was predominantly inhabited by Turks, and Treptow had mainly single-family residences. The common denominator for them was their eastern boundary—the Berlin Wall.

Although each section could be accessed by automobile, the preferred method of travel was by subway. U.S.-licensed automobiles drew considerable attention from the residents. Before every entry, each team member received five Deutsche Marks (DM5) for spending and two subway passes, to ride in and out. Everything else that person did while in that section was at his own expense. However, if mission-related items of equipment were purchased—such as miniature cameras, film, or maps—the team member could be reimbursed from the Detachment Operations and Training Fund as long as he had a receipt.

Internally, we went as “buddy teams” to different locations in the team sector to collect information for our area study/assessment. Every other day we assembled in the team room to update maps and sector folders with the latest data. This was done until February 1983, before the annual ski training.

Ski training was an annual February event held in Federal Republic of Germany. One half of the unit would go to Garmisch-Partenkirchen to ski for ten days and then the other half would go. An airborne operation with in-flight parachute rigging was part of the infiltration. It was a welcome break from the daily activities in Berlin.

In March 1983, twelve members of Detachment A were selected to receive additional “specialized training.” We assembled in a unit classroom to be briefed. A distinguished visitor, William F. Casey, then Director of the Central Intelligence Agency, explained that we were selected to receive advanced training with his organization. This training would be done incrementally over time. The “specialized” training lasted until December 1983. The last session was conducted in Munich, Germany.

We received our instruction from current and retired operatives in the Paramilitary Branch. The hands-on training was quite interesting and beneficial. We shared this with our teams. Some aspects of the experience were funny. Our language and cultural skills were better than the operatives. None of the trainers spoke any German. One day they became lost in the city and called to ask for directions. When asked to pinpoint themselves with street signs, their reply was: “We’re at the corner of Umleitung and Einbahnstrasse.” None of us could help them because they were reading signs for a detour on a one-way street. Eventually, they found their way back to the Detachment.

In July 1983, Team One attended Special Operations Training (SOT) at the Mott Lake facility on Fort Bragg, North Carolina. This provided another opportunity. Teams typically going to SOT would fly commercially from and to Berlin. This was not the case for Team One. We were chosen to make the first long-range infiltration from Berlin to Fort Bragg. On 5 July 1983, we boarded the Duty Train to Frankfurt. From the Frankfurt train station we were taken to Rhein-Main Air Force Base. That evening we boarded a U.S. Air Force MC-130 aircraft to the United States. After a long, uncomfortable night and three mid-air refuelings, we began in-flight parachute rigging. At 1100 hours on 7 July 1983, we jumped on St. Mere-Eglise Drop Zone at Fort Bragg and were trucked to Mott Lake for training. The training at Mott Lake honed our CT skills and demonstrated our competence as a cohesive, well-trained force. After CONUS leaves, the team returned to Berlin in August 1983.

During our absence, LTC Katz placed more emphasis on our OPLAN missions. He used the 10th Special Forces Group, Fort Devens, Massachusetts, Combined Area Studies Mission Analysis Program (CASMAP) to do this. CASMAP focused each team’s efforts and its missions by requiring exceptionally in-depth studies of assigned areas of operation. Though team assignments and missions had previously been closely guarded, once CASMAP began, strict compartmentalization became an obsession.

When a team was assembling information, it posted a “CASMAP PREP” sign on its team room door. The unwritten rule was that only team members could enter. In October 1983, the commander and sergeant major scheduled team brief-backs to assess knowledge and effort to date on areas of operation. CASMAP provided the directional and organizational guidelines needed to address all aspects of team area studies.

Since Team One was a “stay-behind” team, the S-2 arranged for “Ring” and “Wall” Flights. The U.S. Army Flight Detachment, Berlin, flew these fixed-wing and helicopter missions. Ring Flights were routinely flown by the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence, U.S. Commander of Berlin (ODCSI-USCOB) and involved flying a twenty kilometer circle around the city of Berlin. This flight originated at Tempelhof Military Airport and flew over the Russian and East German military installations located in the City of East Berlin. It afforded the observer a “birds-eye” view of the opposition to note any changes in unit equipment and disposition.

Wall Flights also originated at Tempelhof and were flown in a UH-1H “Huey” helicopter along the entire length of the Wall separating West Berlin from both East Berlin and East Germany. The construction of the Wall could be surveyed. Surrounding areas and possible access points were identified. It became apparent that the Wall would be a formidable obstacle to breach. Elaborate efforts had been undertaken to prevent entrance or escape. While team members updated and refined the Team CASMAP efforts, Team One was chosen to participate in Det A’s final mission.

The early November 1983 mission was to support the Joint Chiefs of Staff–directed FLINTLOCK 1984, Exercise FLEET DEER. At the same time, everyone was told that Det A was to be inactivated by December 1984. FLEET DEER was designed to evaluate escape and evasion (E&E) routes and procedures for the rescue of downed pilots or other friendly personnel seeking to return to Allied control. Special Operations Command Europe (SOCEUR) in Stuttgart, Germany, dispatched operational cells to find and survey contact points and to re-establish contact with locals who had originally assisted in establishing the E&E net. That done, the team returned to Berlin in December 1983 to revise and improve contact point target folders, assemble maps and refine operational cell procedures.

During this FLEET DEER preparation time, LTC Katz and Sergeant Major Terry Swofford were reassigned. Major Terry A. Griswold had assumed command of Det A with Master Sergeant Gil Turcotte as the sergeant major. Brigadier General Leroy N. Suddath Jr., Commander of the Berlin Brigade, was slated to command the U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School at Fort Bragg that summer. Suddath had no previous special operations experience, so Griswold arranged a pre-FLEET DEER mission brief. As the officer in charge of the E&E net, I provided a very basic mission brief. We answered his questions and he appreciated the briefing. During FLEET DEER, Griswold arranged for him to ride the aircraft during the airborne insertions of 10th Special Forces Group teams into Germany from England. Suddath also visited Stuttgart and received an operational briefing on FLINTLOCK 1984 from the SOCEUR staff.

The exercise was quite successful for Team One and served not only to validate the E&E net, but helped team members with their CASMAP preparations. After FLINTLOCK 1984 Det A’s operational function was terminated. This triggered the stand down of the Detachment.

Unit inactivations can be extremely difficult or relatively easy. Success hinges on a thorough plan. In this respect, the Detachment was fortunate. Griswold, Turcotte, and the staff maximized the time available while minimizing the stress in each task. Staff NCOs used personal initiative at every opportunity. The two areas of most concern were individual reassignments and disposition of unit equipment. Griswold and Master Sergeant LeRoy F. Miller, the S-1 NCOIC, had an SF assignment person from Fort Bragg come to the Detachment to discuss every reassignment. Each SF soldier received an assignment beneficial to his respective career field. Master Sergeant Ed Cox, the NCO in charge of unit supply accounted for, transferred, and turned in all Army and non-standard clothing and equipment. The only Report of Survey was for four U.S. Army lensatic compasses. All Federal Republic of Germany operational funds were closed with the Berlin Brigade Finance Office.

Reassignment meant that many Det A soldiers would return to standard SF units. To prepare them, Griswold and Turcotte devised a military stakes course. This insured that the men were highly fit and could perform Skill Qualification Test tasks. Each team negotiated the course together and could not begin a station task until all team members were present. Teams were timed. The fastest received awards. It was well received. Griswold and Turcotte also organized a “jump fest” parachute badge exchange with the German Airborne at Braunschweig, Germany.3

When Griswold left Berlin on 8 December 1984, I was the last commander of ten men. Master Sergeant Glen Watson became the sergeant major. Those final “clearing out” days were spent turning in station property, “sanitizing” (clearing of classified material) team and equipment rooms, and cleaning. The S-2 NCOIC, Master Sergeant Lawrence W. Coleman, checked each room for classified materials.

We were a group of very long-faced soldiers not only because we had to close the Detachment, but also because we realized that we would probably never have an experience like this again. On 16 December 1984, I gave the Chief of Staff of the Berlin Brigade the final situation report from Detachment A. He was pleased that everything had progressed well and thanked all of us for the effort. In parting, he asked me how it felt to be the last commander of Detachment A. I replied: “Sir, with all due respect, I wish it hadn’t been me.” Wishing everyone a Merry Christmas, I reported to the ODCSI-USCOB for duty until my departure from West Berlin in April 1985.

The locking of the doors in Detachment A on 17 December 1984 marked the end of a one-of-a-kind unit. From inception to inactivation, Detachment A was always considered a force multiplier. The Soviet Military Liaison Mission’s daily checks revealed how important the Special Forces was to the Soviets. It will probably never be known what impact Detachment A had on Soviet war plans for Berlin. For those fortunate enough to have served in Detachment A, Berlin, it will always be an unforgettable chapter in our lives.

POST SCRIPT

As with all experiences, the passage of time brings reflection and recollections. Here are a few observations on the mission and the unit:

- Survivability of Detachment members in a general European war scenario was questionable. Despite relaxed grooming standards and civilian attire, inadequate documentation to pass cursory enemy checks endangered every operator.

- Not knowing where pre-positioned caches were located did not support an unconventional warfare effort by stay-behind teams.

- Dependent evacuation in the event of hostilities was never adequately addressed nor planned.

- Assignment of young SF soldiers lacking the maturity to blend into the environment brought negative attention to the Detachment.

- Command and control relationships in the event of war were unclear to the SF operators.

- Officers should not be assigned to units like Detachment A as their first SF assignment following the SF Qualification Course. Captains who have previously been team leaders and who have demonstrated their maturity should be carefully screened for a sensitive assignment like this.

Thanks to Sergeant Major (Retired) Gil Turcotte, Don Cox, Colonel (Retired) Darrell W. Katz, and Bruce H. Siemon who provided invaluable information and insight to this article.

ENDNOTES

- Headquarters, U.S. Army, Europe, The U.S. Army in Berlin, 1945–1961, USAREUR NO. AG TS 2-102, USAREUR GC/28/62, USASOC History Office Files, Fort Bragg, NC. [return]

- Lieutenant General William J. Livsey, Commanding General, VII Corps, Letter of Appreciation to Commander, Detachment A, Berlin Brigade, 21 October 1982, author’s personal files. [return]

- Gil Turcotte, e-mail to Eugene G. Piasecki, 2 April 2006, author’s personal files. [return]

- Data and figure from www.berlin.de/rbm-skzl/mauer/english/figures.htm [return]