DOWNLOAD

This issue of Veritas is devoted to the nation of Colombia and the long-standing involvement of the United States in that Latin American country. The United States Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF) have a history of engagement with the Colombian military reaching back more than forty years. This issue provides an introduction to the history of Colombia, describes the nature of the conflict within the country, and looks at the forces on both sides. The goal of this issue is to provide a primer on Colombia and capture the history of ARSOF in this complex and troubled nation.

In studying the history of the United States, the term “Special Relationship” is generally applied to the nations of Great Britain and the Philippines. The term connotes the unique connection between the countries—in the first case, it is rooted in the U.S. beginning as a British colony, and in the second, the status of the Philippines as America’s one true colony. In terms of the U.S. involvement in Latin America, the commitment of the United States to the country of Colombia qualifies for the status of a special relationship. Over the last sixty years, in the often checkered history of Colombia, the presence of the United States has been a significant factor.

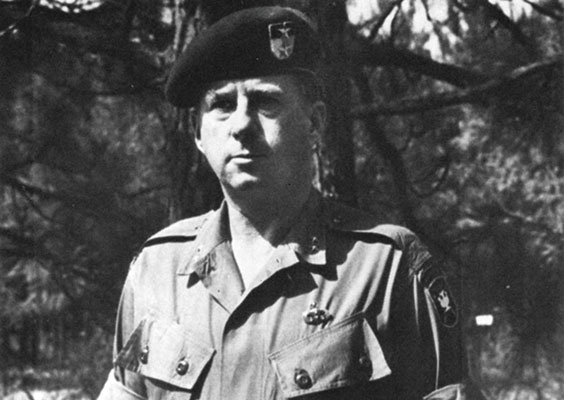

In November and December of 1959, a joint State Department and Central Intelligence Agency defense team visited Colombia to conduct an assessment of conditions in the country brought about by the steadily escalating cycle of murder known as La Violencia. The team’s analysis recommended a comprehensive package of nation-building incentives to attempt to halt the wide-spread killing that had taken the lives of 200,000 Colombians over the preceding ten years.1 The lack of government control of large areas of the country, entrenched poverty and lawlessness, inequitable land distribution, and a growing threat from left- and right-wing insurgents posed a serious danger to the viability of the Colombian nation. The 1962 visit by Brigadier General William P. Yarborough resulted in the formulation of Plan Lazo, which emphasized the need to protect the outlying municipalities with some type of civil defense force.

The United States chose to concentrate on the security aspects of the problem and, over the next fifty years, the conflict grew into a large-scale war fueled by narcotics trafficking, petroleum revenues, and a state of ever-increasing violence.

An in-depth analysis of the complexities of the Colombian situation is beyond the scope of this article. In essence, in the 1970s and 1980s, two elements, narcotrafficking and anti-government insurgents, grew in tandem to the point where each became a viable threat to the stability of the government. The Colombian government chose to approach the issue as a criminal one using the National Police to combat the problem. The Colombian Army deliberately did not get involved and the result was the ceding of large areas of Colombia to the insurgency. The subsequent rise of right-wing paramilitary forces resulted in a situation in which the life of the people in the rural areas was intolerable.2 In combination, these three factors threatened to destroy the third-most populous country in Latin America. Despite the eventual destruction of the powerful Medellín and Cali drug cartels in the 1990s, Colombia still remains the largest producer of cocaine in the world and is the second-largest supplier of heroin to the United States.3 The U.S. war on illicit drugs and, post-9/11, the increased emphasis on counter-terrorism have inextricably linked America and Colombia in a special relationship.

In 1987, the United States launched Operation SNOWCAP, an initiative of the Drug Enforcement Agency. A coordinated twelve-country effort to disrupt the growing, processing, and transportation systems supporting the cocaine industry, SNOWCAP put the majority of the interdiction effort in Bolivia, Ecuador, and Peru.4 While included in the operation, there was not a significant decrease in cocaine production in Colombia.

“The drug trade has a terrible impact on the United States. There are 50,000 drug-related deaths yearly in the United States—with 19,000 directly attributable to drugs,” noted Paul E. Simóns, Acting Assistant Secretary of State for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs during testimony before the Senate Drug Caucus in 2003.5 “Directly linked to the illicit drug trade is the scourge of terrorism that plagues Colombia. Colombia is home to three of the four U.S.-designated foreign terrorist organizations in this hemisphere.”6 The result of this two-fold problem is a long-standing American presence in Colombia, in particular ARSOF and personnel from the Department of State engaged in counter-narcotics activities. Most of this support is manifested in the U.S. support for Plan Colombia.

The Colombian government developed Plan Colombia as an integrated strategy to address the most pressing of Colombia’s problems. Targeting the “illegally armed groups” within the country, combating the narcotics industry, strengthening the government’s presence in outlying areas, and bolstering the Colombian economy are the fundamental precepts of Plan Colombia.7 The $7.5 billion plan requires $4 billion from Colombia and $3.5 billion from the international community. The United States pledged $1.3 billion to support the projected six-year plan as part of the U.S. Andean Counterdrug Initiative.8 The U.S. assistance falls into five areas.

The first of the five components is support for human rights and judicial reform in Colombia. $112 million from the U.S. part of the Plan Colombia assistance is earmarked for a broad program designed to heighten awareness of the principles of human rights, strengthen democracy and the rule of law, and assist with a comprehensive program of judicial reform.9 The second component concerns the expansion of counter-narcotics operations in southern Colombia. It funded two more counter-drug (CD) battalions to form a CD brigade in the Colombian military. The remaining money was to procure and maintain fourteen UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters, thirty UH-1H Huey II helicopters, and fifteen UH-1N helicopters.10 Other components include alternative economic development to assist small farmers growing coca to transition to legal economic activity and increase capability for the Colombian military to protect the vital Cano–Limon petroleum pipeline. To better interdict narcotics flow, the Colombian National Police were provided two additional UH-60 Black Hawks, twelve UH-1N Hueys, and $20 million to purchase Ayers S2R T-65 agricultural spray aircraft.11

Developed by Colombian President Andrés Pastrana (1998–2002) and presented to the U.S. Congress in 1999, Plan Colombia emphasizes the eradication of the coca and opium poppy fields, the destruction of the narcotics laboratories, and supports a package of extensive upgrades to the capabilities of the Colombian military and the National Police. In 2001, $760 million of the U.S.-$1.3 billion established a CD brigade headquarters in the Colombia Army with fourteen organic UH-60 Black Hawks and two more Black Hawks for the National Police.12 This program has been expanded by the present regime.

The current president, Alvaro Uribe Vélez, was elected on a platform that promised to take a tougher stand with the illegally-armed groups. Uribe initiated Plan Patriota, an extensive military campaign designed to wrest control of rural areas of the southern and eastern portions in the country from the insurgents. U.S. support for these initiatives has been divided between the State Department and the Department of Defense.

Within the Department of State, the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) provides the structure and authority for the U.S. effort to combat narcotics trafficking worldwide. At the embassy-level, the Narcotics Affairs Section (NAS) “administers bilateral counter-narcotics agreements and advises the Ambassador and U.S. government on counter-narcotics policy.”13 Established at the U.S. Embassy in Bogota in 1985, the NAS personnel work closely with the Colombian National Police Directorate of Anti-Narcotics. The NAS provides counter-narcotics policy and strategy to the ambassador as well as funding, and supports counter-narcotics activities of other U.S. government agencies such as the Drug Enforcement Agency within the U.S. embassy.14 The largest NAS in any American embassy, the section’s efforts complement that of the Defense personnel working with their counterparts in the Colombian military.

U.S. Southern Command is responsible for the training assistance provided to the Colombian military. U.S. forces, predominately the 7th Special Forces Group, provide training in command and staff procedures, basic soldier skills and reconnaissance. U.S. trainers have been a fixture in Colombia for decades and continue to provide training in garrison and planning support to headquarters at all levels.15 The U.S. troops work with the Colombian military and the National Police, both of which are part of the Colombian Ministry of Defense. Post 9/11, the role of the U.S trainers has shifted somewhat from strictly counter-narcotics to counter-narco-terrorism (CNT), although the training in counter-narcotics is integral to the counter-terrorism mission.

As stated in the publications of the INL, “Counter-narcotics and anti-crime programs also complement the War on Terrorism, both directly and indirectly, by promoting modernization of and supporting operations by foreign criminal justice systems and law enforcement agencies charged with the counter-terrorism mission.”16 This combination of counter-narcotics and counter-terrorism shapes the approach taken by the Colombian military and the U.S. troops that train and work with it.

Just as the American military has its own Rules of Engagement (ROE) for Afghanistan and Iraq versus a domestic emergency, one cannot gauge the willingness of the Colombian military and police to take the fight to the narco-terrorists in their country, by U.S. norms. The ROE for the Colombian armed forces (military and police) is the National Legal Code. Similar restrictions apply to U.S. forces employed at home (to restore order during riots or to combat an internal insurgency) without a declaration of martial law or being granted exemption to civil prosecution (posse comitatus, 18 USC§1385).

In this issue of Veritas, the history and scope of the U.S. involvement with Colombia will be examined. A history of Colombia highlighting the post-war years and articles on the friendly and enemy order of battle will establish the basis for an in-depth study of the U.S. role in Colombia. A look at the experience of the Colombian Army and Navy in the Korean War and the effect on the Colombian military from that war provide a framework from which to assess the Colombian approach to international collective security. The key headquarters and elements of the U.S. military presence and the experiences of ARSOF units reflect how CNT missions are carried out by ARSOF. After reading this issue of Veritas it should be apparent why a special relationship exists between Colombia and the United States.