SIDEBAR

DOWNLOAD

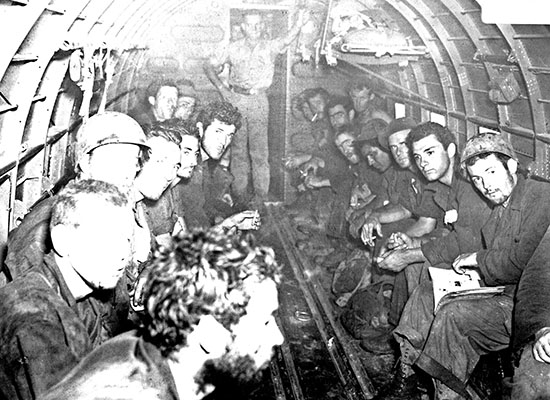

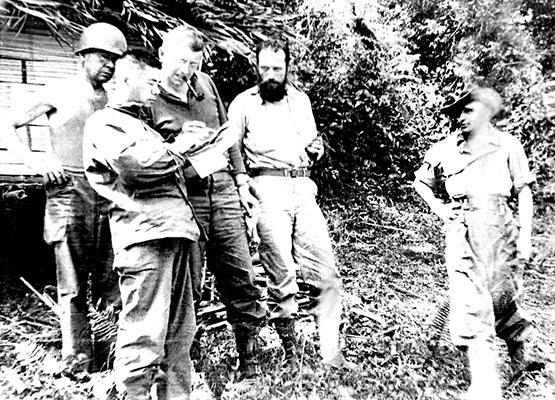

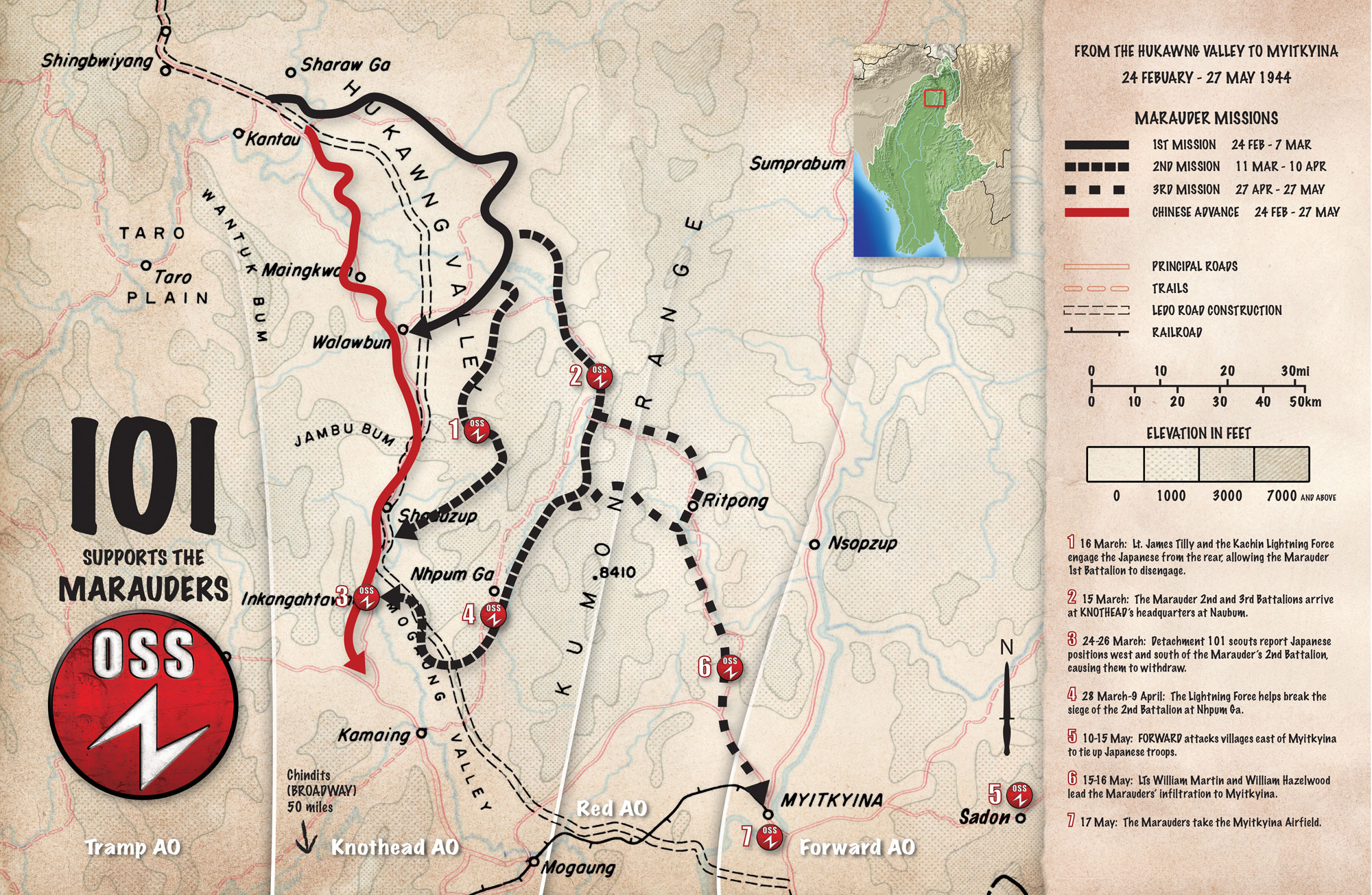

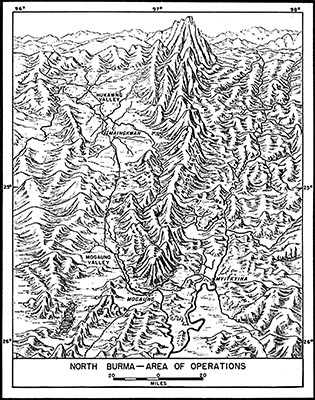

The crowning achievement in Lieutenant General Joseph W. Stilwell’s north Burma campaign from late February 1944 until 3 August 1944 was the hard-fought drive for Myitkyina (Mitch-in-aw). The multi-national operation involved American, Chinese, and British forces under Stilwell’s Northern Combat Area Command (NCAC). The principal American units were the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), popularly known as Merrill’s Marauders, the 10th United States Army Air Force (USAAF), the 1st Air Commando, and Detachment 101 of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Because Detachment 101 supported all the major Allied forces, it was the only ground organization involved in all parts of the campaign. During the long fight, Detachment 101 came of age to become an indispensible asset for the Allied effort. The unit evolved from an intelligence collection and sabotage force to an effective guerrilla element.

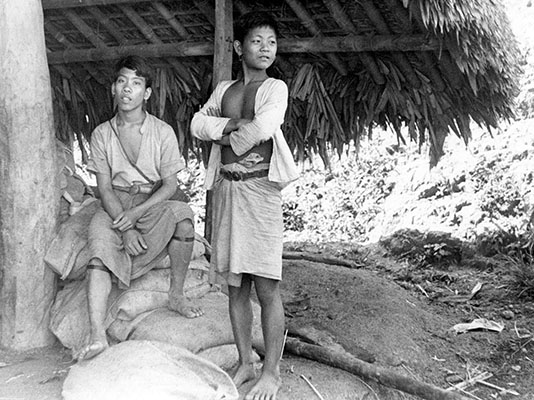

This article is the first of two covering the roles of Detachment 101 in the Myitkyina campaign. Months before D-Day in France, Detachment 101 was conducting one of the earliest Unconventional Warfare (UW) campaigns in coordination with conventional forces. While Merrill’s Marauders and the Chindits fought behind Japanese lines, they did so as conventional elements. Unlike the other forces involved, Detachment 101’s participation was in three phases. During Phase One, the preparatory period (December 1942 through early February 1944), OSS teams infiltrated into north Burma. During Phase Two, (February until 17 May 1944), Detachment 101 supported the 5307th as it maneuvered to capture the Myitkyina Airfield. The unplanned third phase (18 May to 3 August 1944) ended when the city of Myitkyina fell. This first article explains the OSS roles in the first two phases. It is relevant today because Detachment 101 with its Kachin guerrillas was the only true UW force in theater. As such, they were LTG Stilwell’s force multiplier. Effective intelligence collection, liaison, and coordination of indigenous combat forces were the keys to OSS success. One needs to understand the war in Burma to appreciate the importance of the OSS effort.

War came to the British colony of Burma in late January 1942. By May 1942, Japanese forces had summarily defeated a numerically superior British, Burmese, Indian, American, and Chinese defense force. Routed Allied forces and several hundred thousand refugees fled towards the Indian frontier on foot because there were no roads or railroads leading to it from Burma. The skeletons of several thousand people littered the paths and roads used by the Allies when they marched back into Burma.

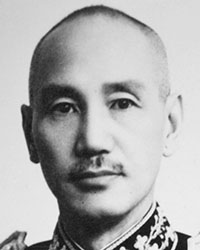

The Japanese had now isolated China. They controlled the major land route to China; the Burma Road that traced its course from Rangoon, Burma to Kunming, China. This road had been critical to resupplying China because the Japanese already occupied that country’s seaports. LTG Stilwell, the U.S. China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater commander, arrived in Burma in time to lead a group of more than a hundred military and civilian Chinese, Americans, British, and Burmese to India. They were forced to walk the final 140 miles when they reached the end of the dirt road. Stilwell said, “I claim we got a hell of a beating. We got run out of Burma and it is humiliating as hell. I think we ought to find out what caused it, go back and retake it.”1 However, this was easier said than done. Stilwell had to contend with rugged, mountainous terrain, bad weather, remoteness, the defeatism prevalent in the British Army, and Chinese politics.

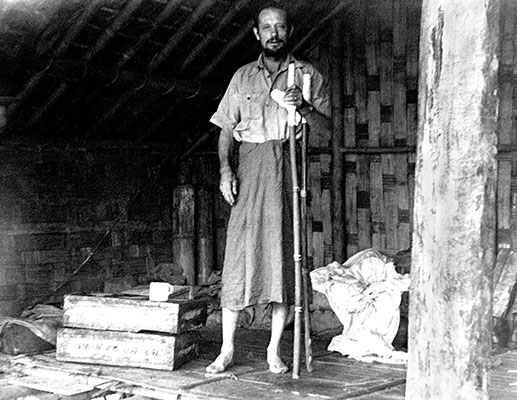

North Burma was one of the toughest fighting environments in WWII. Steep mountainous terrain, the foothills of the Himalayas, dominates north Burma, making foot movement arduous. Detachment 101 discovered it often took thirty days to walk the same distance that a light plane could fly over in an hour.2 The distances involved were extensive: the area of the Marauder’s operations alone was nearly the size of Connecticut.3 Thick secondary-growth jungle—some of it unexplored—slowed ground movement. Leeches, mosquitoes, and diseases plagued fighting men. For instance, the 3,000-man Merrill’s Marauders suffered 296 cases of malaria and 724 incidents of other diseases such as acute dysentery, and scrub typhus by 4 June 1944. They had only been in the field three months. This contrasted sharply with 424 killed, wounded, or missing during the same period.4 High humidity and temperatures well over 100 degrees Fahrenheit were common from March through May. The monsoon season of torrential rains lasted from June through September. Constant moisture rotted or rusted everything. “A cleaned pistol will develop rust pits in 24 hours, a pair of shoes not cleaned daily will rot in a week,” read one Detachment 101 report.5 The CBI Theater was also at the tail end of an overtaxed logistics chain. Confusing command and control arrangements with the U.S. Army Air Forces, and the British, who had supreme command over Burma, caused some to say that the theater acronym stood for “Confusion Beyond Imagination.” But, nothing compared to Stilwell’s difficulties with the Chinese.