DOWNLOAD

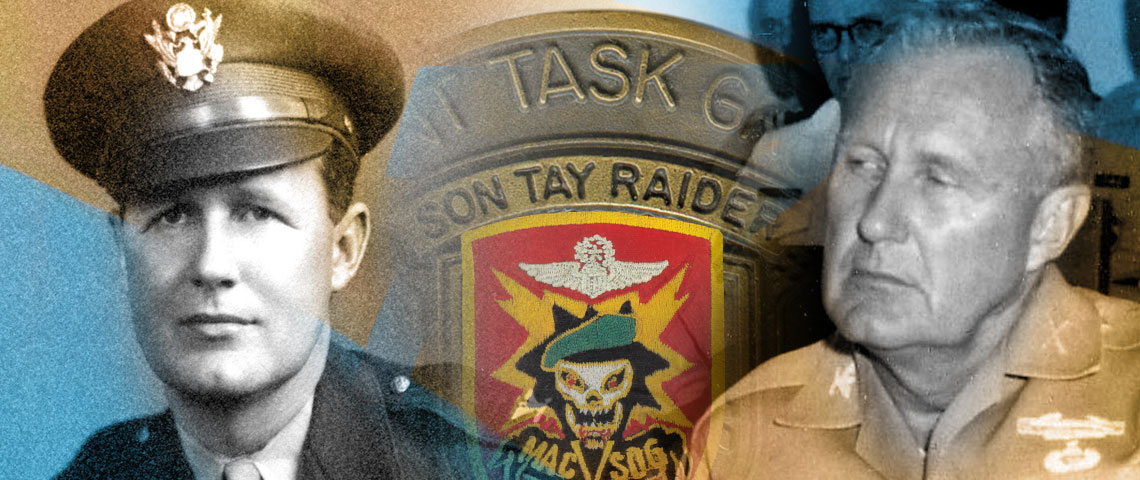

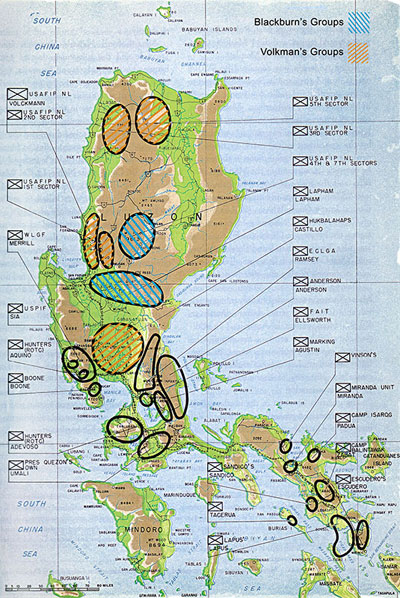

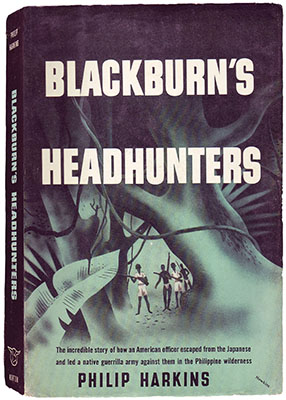

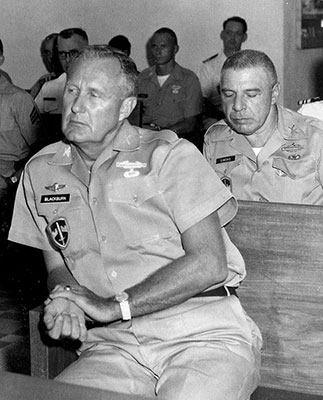

On 24 May 2008 Brigadier General Donald D. Blackburn passed away at his home in Sarasota, Florida. During a career that spanned more than thirty years, Blackburn was instrumental in the development and application of special operations doctrine in the Army. His involvement in special operations began in 1942 when he and Major Russell W. Volckmann refused to surrender to the Japanese in the Philippines. In the late 1950s and early 1960s he served in Vietnam as a provincial advisor and was the commander of the 77th Special Forces Group. He returned to Vietnam in 1965 as the second commander of the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam-Studies and Observation Group (MACV-SOG). He concluded his career in special operations as the Special Assistant for Counterinsurgency and Special Activities (SACSA) in the Office of the Secretary of Defense where he was the architect of the Son Tay prisoner of war rescue mission. This article will briefly trace his career and show the impact Blackburn had on Army Special Operations.

Born on 14 September 1916 in West Palm Beach, Florida, Second Lieutenant (2LT) Blackburn was commissioned in the Army Reserve from the University of Florida in 1938. After less than two years at Georgetown University Law School in Washington, DC, he sought and accepted an active duty assignment in the Infantry. In September 1940 Blackburn was assigned to the 24th Infantry Regiment at Fort Benning, Georgia as the communications officer. The 24th Infantry was a segregated black regiment with white officers. During the summer of 1941, the 24th Infantry Regiment took part in the Louisiana Maneuvers, the largest of the pre-War Army field exercises. By October 1941, LT Blackburn had orders to serve as an adviser to the Philippine Army, then under the command of retired Major General (MG) Douglas A. MacArthur.1

In the Philippines, First Lieutenant (1LT) Blackburn was to advise the headquarters battalion of the 12th Infantry Regiment located at Baguio, 175 miles north of Manila on the island of Luzon.2 Training the ill-equipped and poorly-led conscripts proved to be a daunting task. The Japanese Army invaded the Philippines on 8 December 1941, landing on Luzon and Mindanao. On Luzon, major forces landed at Lingayen Gulf and rapidly forced the American and Philippine forces back onto the Bataan Peninsula. War Plan Orange, the U.S. plan for the defense of the Philippines dictated a defensive stand on Bataan.3 The commander of the Philippine battalion relinquished his command to Blackburn, who tried to stop a Japanese amphibious landing force. After firing the first shots, Blackburn’s raw troops fled in panic and he was forced to collect the unit and head towards Bataan.

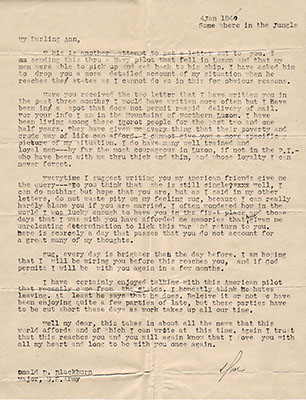

As the Japanese onslaught continued, Blackburn and MAJ Volckmann, the advisor to the Philippine 11th Infantry Regiment, decided that rather than surrender as LTG Jonathan M. Wainwright, the commander of U.S. Forces in the Philippines had ordered, they should evade capture and escape to the northern mountains of Luzon.4 They broached their plan to Major General William E. Brougher, commander of the 11th Division (Philippine Army), who remarked that were he a younger man, he would pursue the same course.5 That evening, as surrender bonfires were lit around the U.S. perimeter, Blackburn and Volckmann crept through the porous lines and fled north with the intent of working their way into the mountains. They were ill-prepared for the arduous journey to come.