DOWNLOAD

Ranger Insignia

The withdrawal of the French Expeditionary Corps from Vietnam in April 1956 meant that Lieutenant General (LTG) John W. “Iron Mike” O’Daniel and the United States Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) were the only “foreign” advisors left to support all services in the armed forces of South Vietnam. From 1956 through 1960, LTG O’Daniel and his successor LTG Samuel T. “Hangin’ Sam” Williams patterned the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) to resemble the post-Korean War United States Army.1 The problem with this was the ARVN strategic focus became defense against an external invasion rather than fighting an internal insurgency.2 As the level of fighting intensified, Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem on 15 February 1960, ordered his regional and divisional commanders to initially form Ranger companies composed of volunteers from the Army, the Reserves, retired Army personnel and the Civil Guard.3 Diem’s plan to expand the Rangers into battalions and groups became a reality in January 1961 after U. S. Ambassador to Vietnam, Elbridge Durbrow, withdrew his opposition to Diem’s proposal to increase the strength of the South Vietnamese Army by 20,000 men.4

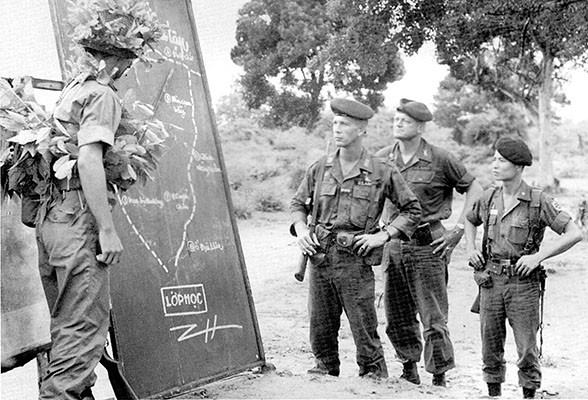

Despite the objections of General Williams, General Isaac D. White, the Commander, U. S. Army Pacific, and Admiral Harry D. Felt, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific, the Eisenhower administration supported President Diem’s decision to create Rangers. To demonstrate American support, mobile training teams (MTT) from Colonel Donald D. Blackburn’s 77th Special Forces Group at Fort Bragg, NC were sent to South Vietnam. Commanded by LTC William Ewald, their mission, directed by LTG Williams, Chief MAAG, was to establish Ranger training centers at Da Nang, Nha Trang and Song Mao to train selected South Vietnamese soldiers as cadre to form the new Ranger companies. Between 5 April and 12 November 1960, the Special Forces teams conducted four training cycles at each location. Each cycle lasted four-weeks and consisted of 423 hours of instruction and training.5 Approximately 1,000 Rangers were qualified in day and night rifle marksmanship, and trained in advanced fieldcraft and patrolling techniques. More importantly, after completing the second cycle, the Special Forces trainers reverted to advisors/mentors. The Vietnamese Ranger course graduates presented the remaining instruction.6 Assigning American advisors to the Vietnamese Ranger units was formalized during the Kennedy administration (1961-1963). Ranger advisors continued being assigned through 1973 despite U.S. force reductions that began in 1969.7

In February 1962, a unified (Army, Navy, Air Force) headquarters, the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), replaced MAAG. MACV’s mission was to coordinate all American military activities in South Vietnam.8 In mid-1964, the U.S. MACV J-3 (Operations) supervised all American advisory programs including the Ranger command.9 According to the Table of Organization and Equipment (TOE) MACV Ranger Advisory teams were authorized eight personnel: an Army Lieutenant Colonel to be the senior advisor at group level; an Army Major at the battalion level; and six noncommissioned officers with combat experience from WWII, Korea, and/or Vietnam or former U. S. Army Infantry School Ranger Department instructors. In reality, advisory teams consisted of a Captain, a Lieutenant, two Sergeants, and a Radio-Telephone Operator (RTO). Completion of U. S. Army Ranger training was not a requisite. Some Ranger advisors attended the Military Assistance and Training Advisory Course (MATA) at the U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Institute for Military Assistance (USAJFKIMA) at Fort Bragg, NC and/or Vietnamese Language School. Experience was acquired in combat.10

The ARVN Ranger advisor mission was simple. The American advisor was expected to be with his Ranger unit every time it was in the field to provide assistance and counsel on everything from preparing operational plans to executing them in combat with little dedicated support from either American or South Vietnamese sources.11 To help achieve success, the advisor coordinated for available U.S. fire support (artillery, air strikes and helicopter gunships, and naval gunfire), armor, and medical evacuation. Often, he escorted and arranged specialty teams such as dog handlers.12 Ranger advisors performed these missions through 1973 despite the U.S. Vietnamization policy which began reducing the American support and advisory mission on 1 July 1969.13

The goal of Vietnamization was to create strong, self reliant South Vietnamese military forces while fostering political, social, and economic reforms as American forces withdrew.14 This meant two important operational changes for the Vietnamese Ranger units: first, as the American advisors completed their tour of duty they were not replaced; second, the thirty-seven Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) camps, established and supported by the 5th Special Forces Group along the Laotian and Cambodian borders, became part of the Vietnamese Ranger Command. By 31 December 1970 these changes had been implemented. When the American advisors were gone, the Vietnamese Rangers continued to fight the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army (NVA) often to the point of decimation. When Saigon fell to Communist forces in 1975 those surviving Ranger unit commanders, whom the North Vietnamese considered dangerous, were sent to “reeducation camps.” Like their American counterparts the Vietnamese Rangers could always be proud of their motto: “Biet Dong Quan Sat” which means “Special Action Warrior—Kill.”15