ARSOF in the

Korean War: Part V

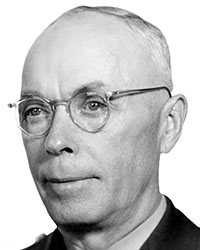

Right Man for the Job: Colonel Charles H. Karlstad

We're Asking the Reds to SURRENDER-PLEASE! Collier”s, 13 December 1952

Herbert Avedon: Making Psywar a Career

The Psywar Center, Part II: Creation of the 10th Special Forces Group

DOWNLOAD

The Korean War presented the United States with challenges unlike any previously faced in the Twentieth Century. In contrast to World War II, when the national objective was the unconditional surrender of Germany and Japan, the political and military ramifications resulting from the entry of Communist China into the conflict altered the U.S. campaign to one designed to reach a negotiated settlement between the warring factions. The Korean War was the first major conflict in which the United States engaged without a formal Congressional declaration of war, but rather conducted under Presidential authority.1 The U.S. prosecution of the war can be broken into five distinct phases.

The initial phase of the war was the reestablishment of the pre-War South Korean national boundary along the 38th Parallel following the 25 June 1950 attack by North Korea. In the second phase, General (GEN) Douglas A. MacArthur’s stated goal of destroying the North Korean Army led to the drive north to the Yalu following the breakout from the Pusan Perimeter and the Inch’on landing. The entry of the Chinese Communist Forces (CCF) into the war pushed the United Nations (UN) forces back in Phase Three, necessitating the reestablishment of the line along the 38th Parallel in Phase Four. The fifth and final phase of the war was the effort by both sides to seize key terrain and establish the most advantageous position during the protracted armistice negotiations. By necessity, every aspect of the U.S. military effort was adjusted to reflect the change from the initial offensive against North Korea to subsequent operations designed to strengthen the United Nations position in the Armistice negotiations. This included adapting the priorities and capabilities of the Psychological Warfare (Psywar) effort to the changing nature of the war.

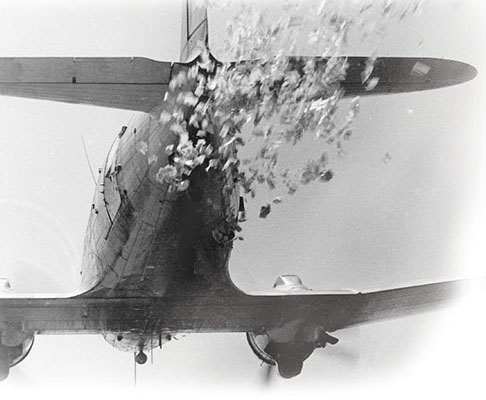

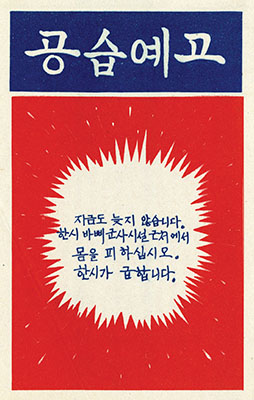

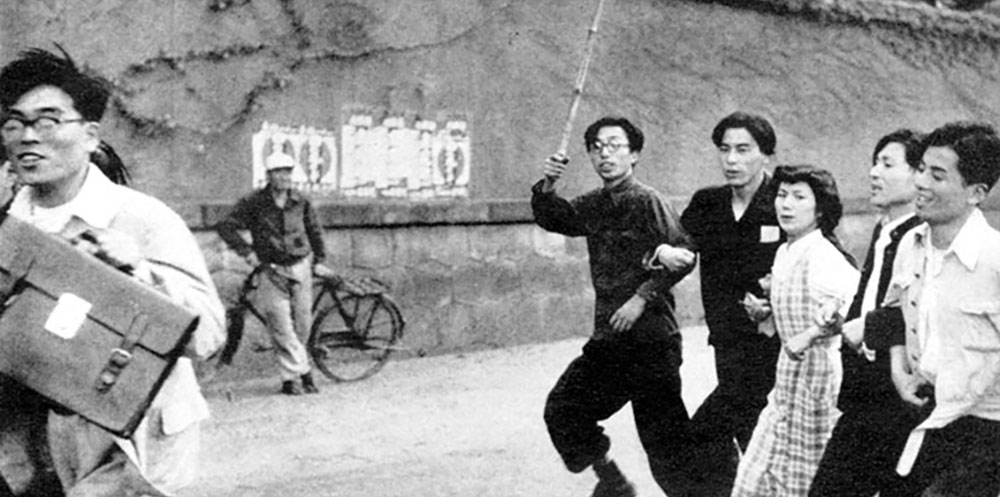

Psywar was a critical element of the U.S. campaign from the initial phases of the war. The articles presented in this issue of Veritas run the gamut from the strategic to the tactical and cover the period from mid-1951 through the signing of the Armistice in 1953. The focus is largely, but not exclusively, on the radio broadcasting operations conducted in support of the UN effort. Told largely through the words of the participants, each article describes the establishment of the radio broadcasting capability in South Korea, the expansion of the radio network, the technical support required to get the stations on the air and an American perspective on the 1952 May Day riots in Tokyo that followed the official end of the U.S. occupation of Japan. Included are articles on the implementation of strategic Psywar operations, the establishment of the Psywar Center and early 10th Special Forces Group, and biographies of two individuals prominent in the development of the Army Psywar capability.

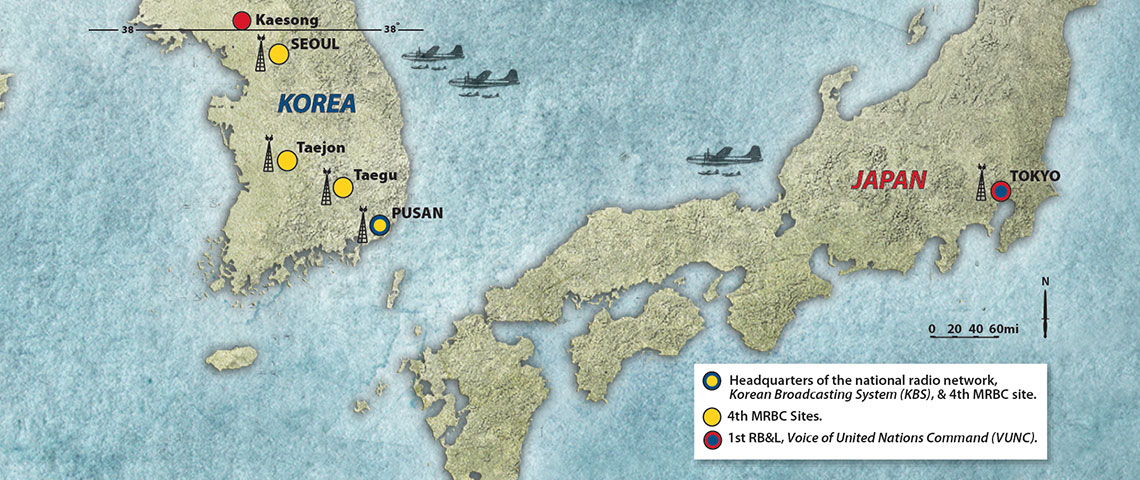

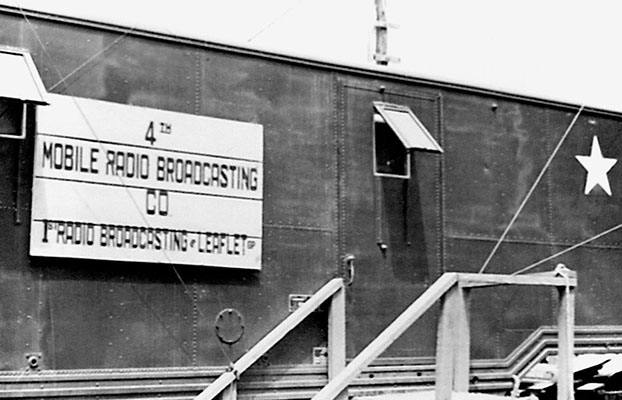

The first Psywar priority for Far East Command (FECOM) at the outset of the war was the establishment of Radio Tokyo and the Voice of the United Nations Command (VUNC) in order to counter the widespread Communist propaganda. Psywar support was the responsibility of the 1st Radio Broadcasting and Leaflet Group (1st RB&L). Within the 1st RB&L, the 4th Mobile Radio Broadcasting Company (4th MRBC) was the unit tasked with establishing radio stations and developing and executing the radio programming. Headquartered in Tokyo after arriving from the United States in August 1951, the 1st RB&L was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Homer E. Shields. His immediate strategic priority was the program management of Radio Tokyo with the concurrent responsibility of airing the Voice of the UN Command. He then had to focus on the establishment of a radio broadcasting capability in South Korea to regenerate the decimated Korean Broadcasting System (KBS). Support to these two missions fell on the 4th MRBC.

As described in a previous issue of Veritas (Vol. 7, No. 2, 2011), the establishment and operation of Radio Tokyo was handled by the 1st RB&L using all the assets within the Group.2 To resurrect the KBS on the mainland, a four-man detachment led by 2nd Lieutenant (2LT) Jack F. Brembeck was dispatched to Pusan in mid-August 1951 to assess the extent of the wartime damage to the KBS facility and prepare for broadcasting from the city. Soon replaced in Pusan by 2LT Eddie Deerfield, Brembeck moved to Kaesong to replace First Lieutenant (1LT) Jack F. Brennan who was the 1st RB&L liaison officer at the preliminary armistice talks. By October, Radio Pusan was operational and became the focal point of the 4th MRBC effort until the signing of the Armistice.