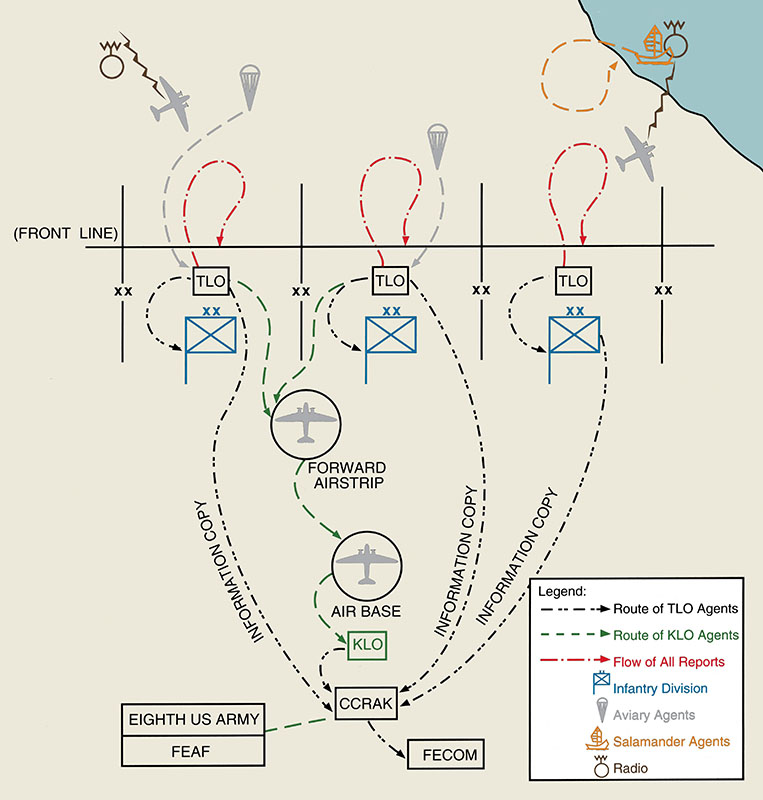

The decision to strengthen the EUSA defensive lines and confine its offensive actions to limited advances ended the fluid phase of the Korean War and started a new period that had far-reaching impacts from the Korean Peninsula back to the United States.19 As U.S. Army general purpose forces were committed to battles to gain control of Korea’s high ground, the EUSA Miscellaneous Division under COL McGee experienced realignments and changes that modified their combat and intelligence collecting capabilities. The first of these initiatives established the Guerrilla Section, EUSA Miscellaneous Division, as an independent organization [designated as the 8086th Army Unit (AU)] on 5 May 1951. On 10 December 1951, the 8086th AU fell under the Far East Command Liaison Detachment, Korea [FEC/LD (K)], 8240th AU. This change made all partisan operations responsible to the Guerrilla Division. It also consolidated TLO operations under the Combined Command Reconnaissance Activities Korea (CCRAK), [AU = TDA].20

Meanwhile, back in the United States, Brigadier General (BG) Robert A. McClure, Chief of the Office of Psychological Warfare (OCPW) in the Pentagon, established the U.S. Army Psychological Warfare Center (PWC) on Smoke Bomb Hill at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. As part of the PWC, a new organization called Special Forces (SF) was being created from an all-volunteer group of combat veterans and those who wanted more of a challenge than the garrison-oriented Army offered. In November 1952, eager to demonstrate SF’s capabilities, BG McClure actively pursued efforts to send newly-qualified SF soldiers to Korea. In early 1953, his repeated attempts finally succeeded and FEC requested fifty-five officers and nine enlisted men from the recently-activated 10th Special Forces Group (SFG).21 However, FEC assigned the SF soldiers as individual replacements and not as members of operational teams. Eager to demonstrate that the SF concept had not been a waste of time and resources, Special Forces-qualified soldiers first reported to the 8240th AU for combat duty in Korea in March 1953.22

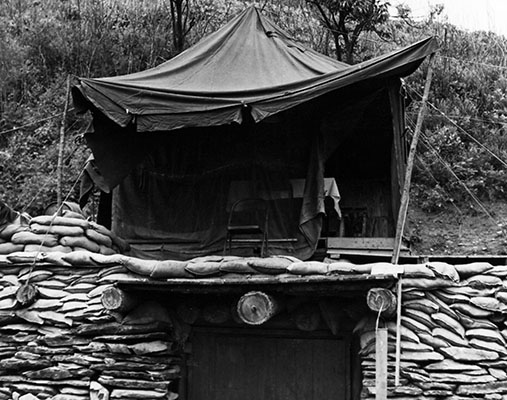

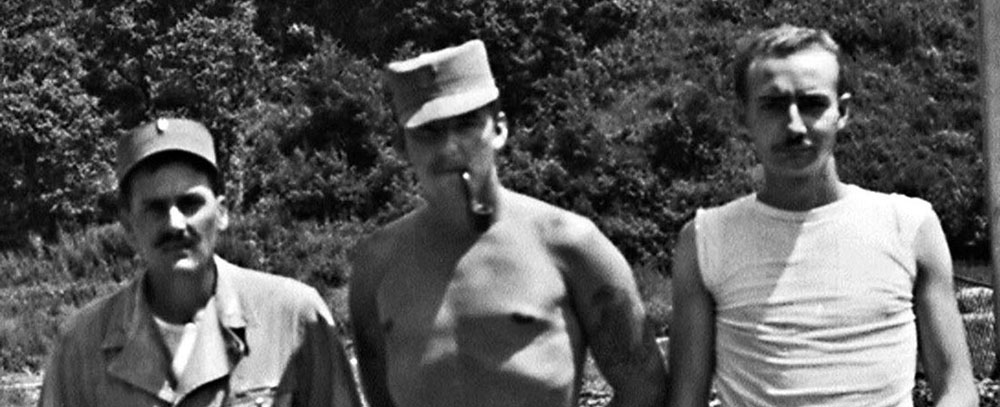

Among the earliest SF arrivals was Second Lieutenant (2LT) George W. ‘Speedy’ Gaspard, a graduate of the first Special Forces Course at Fort Bragg, NC.23 Arriving in the first shipment of SF-qualified men in early March 1953, 2LT Gaspard, a World War II veteran of the 6th Marine Division, was not new to combat. But he soon discovered that the 8240th presented him with operational challenges that he had not anticipated. One of these, that posed a constant threat throughout his TLO team assignments in the 2nd, 40th, and 45th Infantry Divisions, was the possibility that a line-crosser was a ‘double-agent’ even though he had been vetted by that particular division’s intelligence staff. Once discovered, these suspected ‘doubles’ were placed under the watchful eye of the TLO camp’s Korean First Sergeant where they remained until hostilities ended.24 2LT Gaspard remained a TLO team leader until he was transferred to TLO headquarters to become the adjutant on 26 September 1953.25

Arriving in Korea after 2LT Gaspard were Captain (CPT) Charles R. Bushong, First Lieutenant (1LT) Alvin L. O’Neal, Master Sergeant (MSG) John E. Kessling, and Corporal (CPL) Russell A. Shafer. Assigned to the TLO, 7th ID on 3 March 1953, CPT Bushong was followed by 1LT O’Neal, MSG Kessling, and CPL Shafer. While assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division, MSG Kessling volunteered for SF because he “wanted to fill his obligation as a soldier and go to combat,” and he remembered his assignment to the TLO as anything but ordinary.26 Arriving at Camp Stoneman, CA, from Fort Bragg, NC, for overseas processing, MSG Kessling received no orientation briefings. Instead, he was placed on a civilian flight in San Francisco, CA, and finally arrived at the FEC replacement detachment at Camp Drake, Japan after stops in Hawaii and Guam. While at Camp Drake, MSG Kessling attended a two-week “intelligence school,” described as “briefings and made up stuff,” and then flew to K-9 airfield at Pusan, Korea, in a Flying Tiger C-47 aircraft.27

Not SF-qualified, Private First Class (PFC) Russell A. Shafer’s experience was somewhat different. Having already been promoted to Staff Sergeant (SSG) in the New York Army National Guard (NYARNG), and as a graduate of the Infantry School’s Light and Heavy Weapons course at Fort Benning, GA in 1951, Shafer wanted a discharge from the NYARNG so he could enlist in the Regular Army. Because the NYARNG had frozen all equipment and personnel assets anticipating Federalization, Shafer moved to Lawton, OK. There, with the help of an uncle (a Regular Army Warrant Officer stationed at Fort Sill), he accomplished his goal in 1952. Now a Regular Army PFC, Shafer volunteered for Korea after successfully completing the Field Artillery Weapons Maintenance School at Fort Sill, traveling to Japan by troopship from Fort Lewis, WA.