SECTIONS

- From COI to OSS: The Beginning, 1941-1942

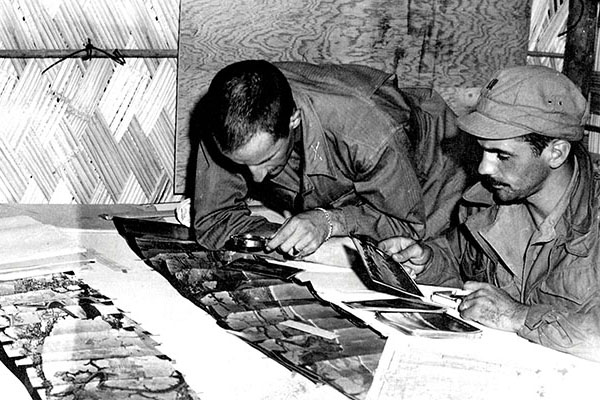

- SECRET INTELLIGENCE

- SPECIAL OPERATIONS

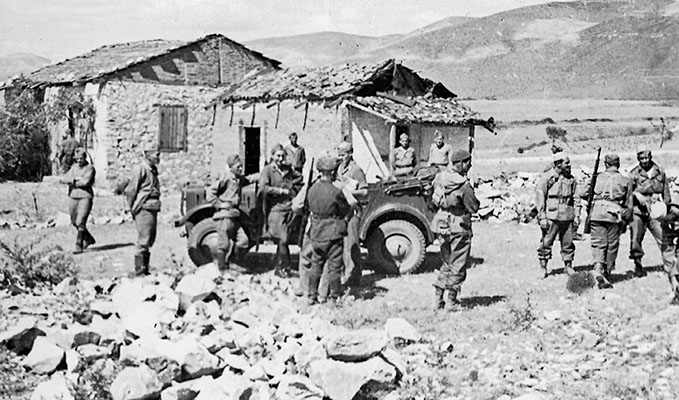

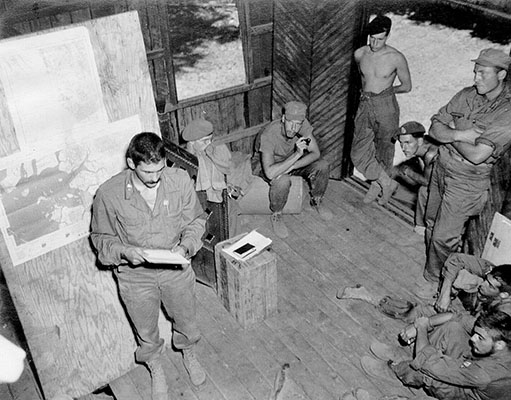

- JEDBURGHS: D-Day 1944 and Beyond

- OPERATIONAL GROUPS

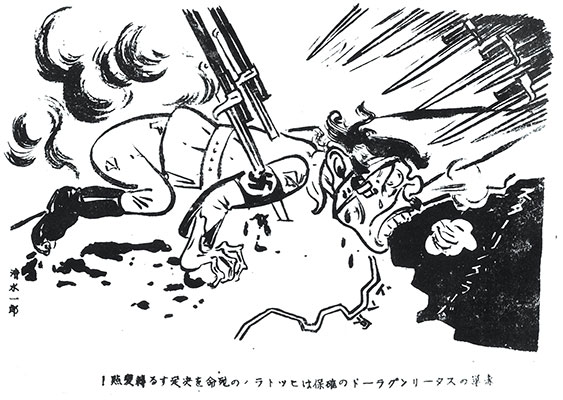

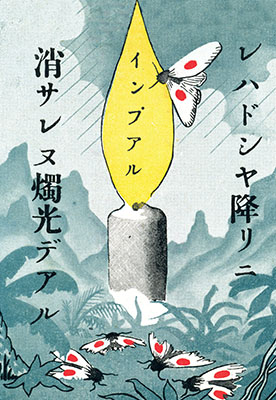

- MORALE OPERATIONS

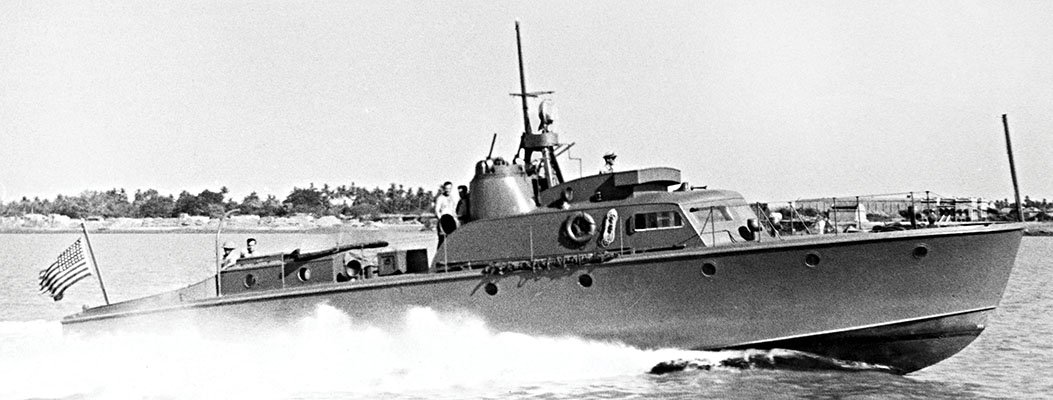

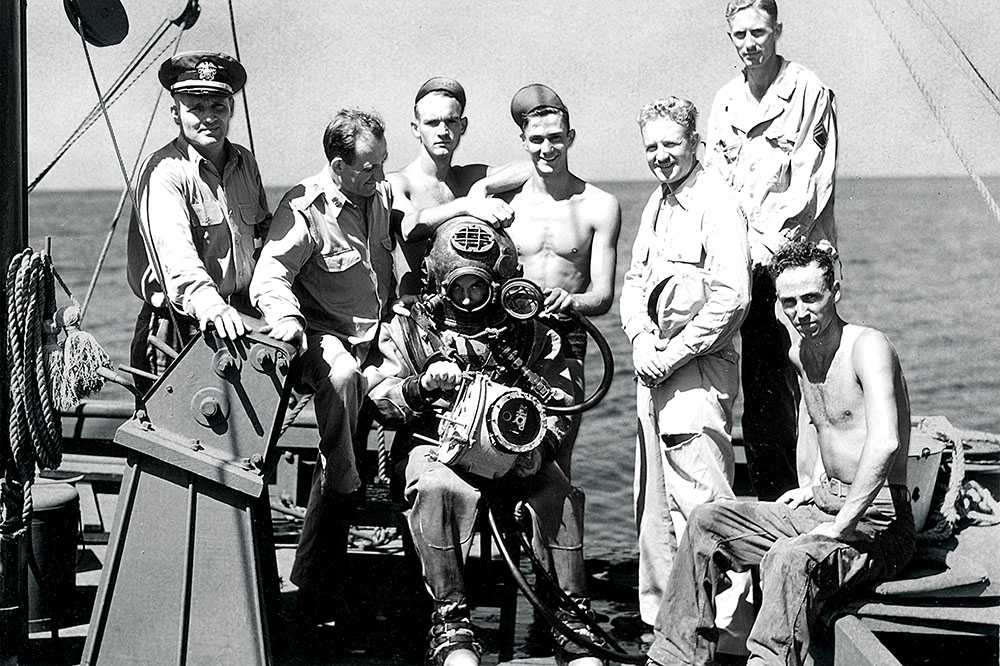

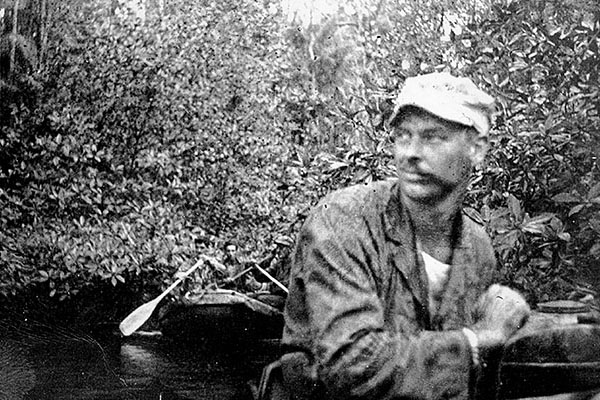

- MARITIME UNIT

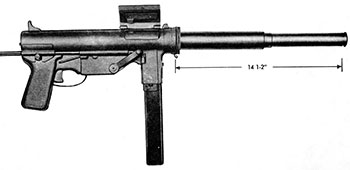

- RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT

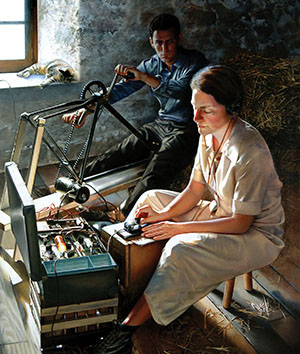

- COMMUNICATIONS BRANCH

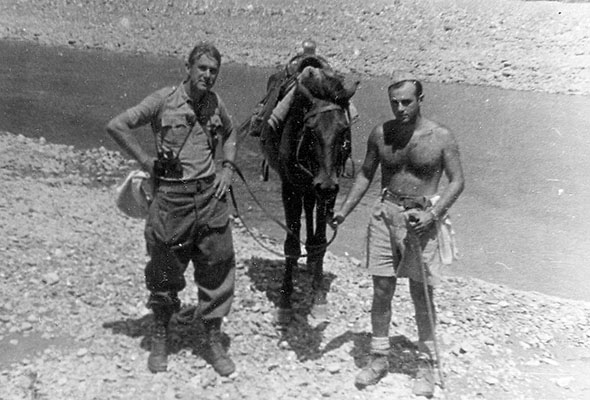

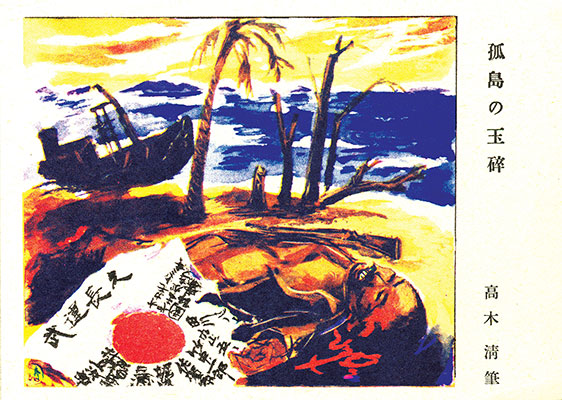

- The OSS in Asia

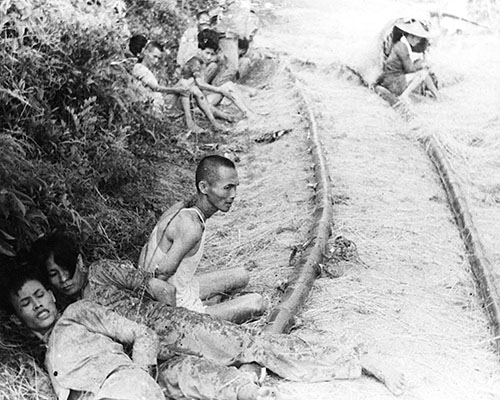

- OSS DETACHMENT 101: 1942-1945

- DETACHMENT 404: 1944-1945

- DETACHMENT 202: 1944-1945

- AN ENDURING LEGACY: 1945-PRESENT

DOWNLOAD

Considered as a legacy unit of the U.S. Army Special Operations Forces, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) has assumed almost mythical stature since World War II. Several OSS veterans, among them Colonel Aaron Bank, Lieutenant Colonel Jack T. Shannon, and Majors Herbert R. Brucker and Caesar J. Civitella brought unconventional warfare (UW) tactics and techniques to Special Forces in the early 1950’s. It should be remembered, however, that the short-lived OSS (1942 to 1945) had two basic missions: its primary one was to collect, analyze, and disseminate foreign intelligence; its secondary one was to conduct unconventional warfare. The first, executed primarily by the Research and Analysis branch (R&A), was considered the most important during the war.

It is the second mission of UW, however, that has received the most attention since WWII. It was this element of the OSS that provided the most exciting stories and which was cloaked by an aura of secrecy and mystery. These UW missions have become the subject of numerous books and several films. This article is designed to serve as a primer on the UW elements of the OSS. It is not an exhaustive look at the OSS, nor does it address every OSS function or branch. Its intent is to provide the reader with a basic understanding of what missions the separate OSS branches had, what the main operational efforts were, and where they took place geographically.