ABSTRACT

On 16 July 2019, the 389th Military Intelligence Battalion (Airborne) was activated at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. First organized during World War II, the 389th will fuse the tactical intelligence efforts of Special Forces, Psychological Operations, and Civil Affairs units, with their higher operational-level commands. This article provides the lineage, operational history, and mission of the newest battalion in the U.S. Army Special Operations Command.

TAKEAWAYS

- Provide intelligence support to the component subordinate units.

- Serve as the core of the J2 for Special Operations Joint Task Force contingency.

- Execute geospatial intelligence (GEOINT) and processing, exploitation, and dissemination (PED) for ARSOF platforms.

- Conduct intelligence training and support standardization of intelligence support to ARSOF.

SIDEBARS

DOWNLOAD

The 389th Military Intelligence (MI) Battalion dates to World War II, with the constitution of the 389th Translator Team on 14 December 1944. Organized per Table of Organization and Equipment (T/O&E) 30-600T (September 1944), “Intelligence Services,” the translator team was authorized one officer and three enlisted men.1 Activated on 27 February 1945 in the Philippines, it consisted of specially trained Japanese American linguists from the Military Intelligence Service (MIS Sidebar).2

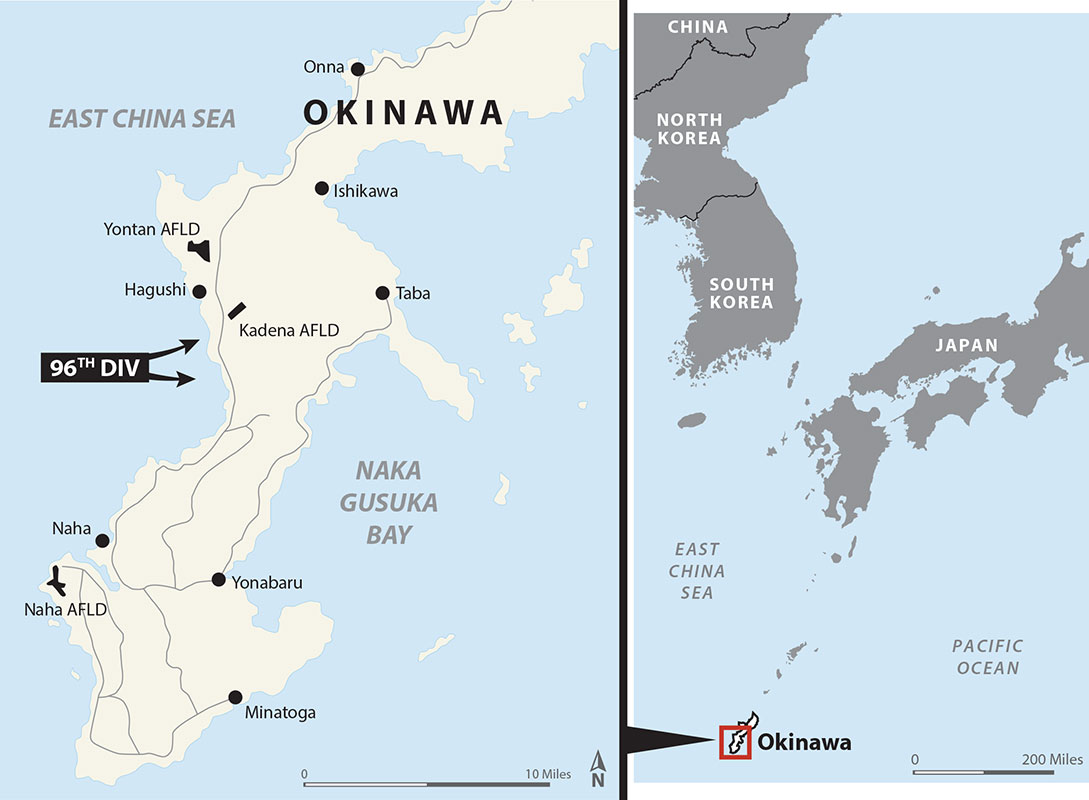

As part of the 314th Headquarters Intelligence Detachment, the 389th Translator Team was attached to the G-2, 96th Infantry Division (ID).3 It saw combat during the Leyte Campaign.4 Afterwards, it was shipped to Okinawa on 26 March 1945 aboard the USS Mendocino (APA-100), as part of the Southern Attack Force. It landed on 1 April at Beach White 1, in the lightly defended Hagushi Beaches area of Okinawa.5

During the ensuing three-month battle, one translator was attached to each of the 96th ID infantry regiments.6 With the battle drawing to a close in late June, the 96th ID concentrated its linguists at their civilian and Prisoner of War collection point to assist with the screening of civilians and interrogating of Japanese prisoners.7 The 389th Translator Team received the Presidential Unit Citation (PUC), awarded in December 2001, for actions on Okinawa.8