SIDEBAR

DOWNLOAD

“There were few less desirable places in which to fight a campaign,” wrote Lieutenant General Sir Geoffrey Evans of the Arakan coast of Burma.1 The Arakan ran south from the Indian frontier along the Burmese coast for 120 miles to the town of Akyab, which marked the furthest advance up the coast by the Japanese Imperial Army. Riven by rivers and chaungs resembling the bayous of Louisiana, the Arakan coast was penetrable only during the summer dry season. The area became a mosquito- and leech-ridden swamp from October to May, when the monsoon dumped over two hundred inches of rain on the land. During that time, access to most of the coast was restricted to watercraft.

The British, established in the region since the days of the Raj, possessed extensive facilities in India and Ceylon from which to launch operations against the Japanese in the Arakan. Joining this effort was the Maritime Unit (MU) of the United States’ Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

Lieutenant (LT) Fisher Howe, U.S. Naval Reserve (USNR) arrived in the South East Asian Command (SEAC) Theater in February of 1944 with the mission to recruit and train a maritime group capable of infiltrating agents into hostile territory, conduct reconnaissance, and execute small-scale sabotage operations.2 General William O. Donovan, Director of the OSS, promised Lord Louis Mountbatten, the theater commander, that the OSS would provide troops from the maritime unit to augment the British intelligence gathering effort. Neither the British nor the United States had sizeable combat power in the theater and the addition of the OSS and their counterparts in the British Special Operations Executive was important.

Fisher Howe estimated that to accomplish the missions promised by Donovan, he would need four fast surface craft with crews; at least thirty of the trained MU swimmers; a like number of small boat (kayaks and rubber rafts) operational men; and a headquarters staff for administration, supply, and operations. On 15 May 1944, a cable went back to Washington for an MU swimming group. Up to this time, Howe was the sole representative of the MU in SEAC, and he industriously built up connections and borrowed individuals from other OSS branches to further the preparation for the arrival of the personnel.

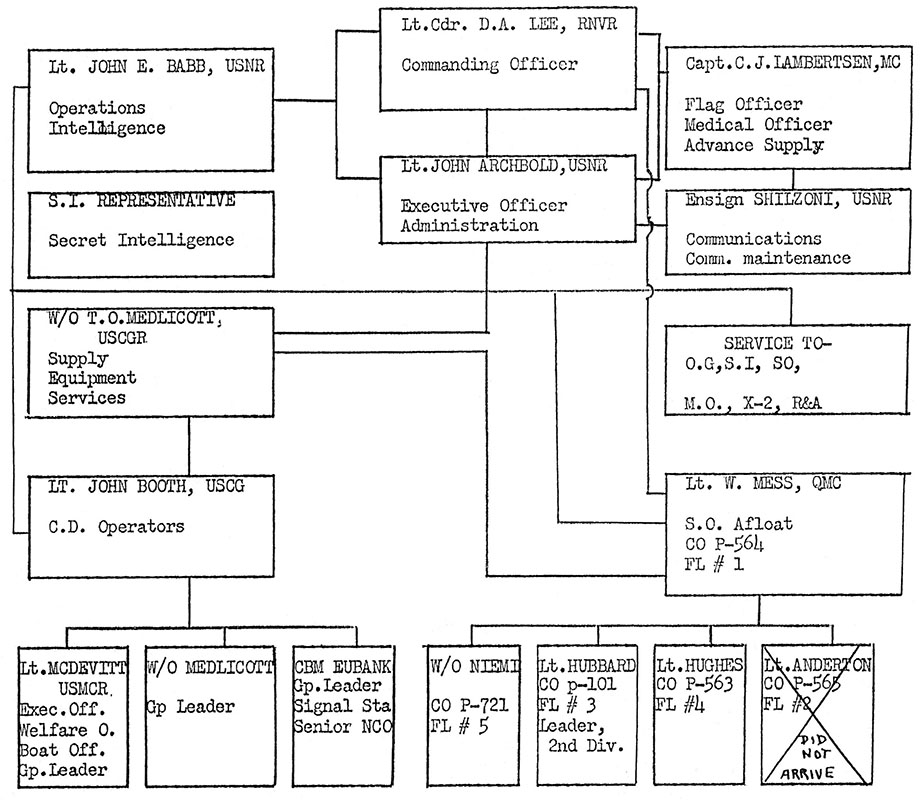

The primary base for MU operations was established on the island of Ceylon (Sri Lanka), initially at the harbor town of Trincomalee. The British maintained an extensive dock and maintenance facility there, and a substantial portion of their fleet in the theater. Howe succeeded in establishing close working relationships with the other U.S. and Allied agencies in the theater, and he contributed his expertise to a number of missions of a maritime nature. Ill health forced Fisher Howe to return to Washington in July 1944, and LT Kenneth Pier, USNR, replaced him. Pier had already been in the SEAC Theater for a considerable time, assigned to the Navy’s Field Photographic Office. His assumption of command of the Maritime Unit coincided with the arrival of Swimmer Group 1 under the command of LT William Horrigan, USNR, with thirty swimmers and assorted support personnel. Group 1 was followed in August with the arrival of Swimmer Group 2 under Lieutenant Junior Grade John Archbold, USNR.

Prior to the arrival of the forces and his own departure, Howe began to look for a more suitable site for the training and operations of the unit. Training of native agents initially took place twelve miles outside Trincomalee at a small outpost called “Camp Y.” In June 1944, the MU moved across the island to the southwest corner and established a base at Galle, about seventy miles south of Colombo. This became the central training facility for the MU, where native agents were introduced to basic demolitions training, the use of the folboat (a collapsible kayak-type craft), infiltration, and intelligence gathering. The natives were recruited from throughout the theater, and the MU personnel trained Chinese, Burman, Thai, Malay, and Sumatran agents, few of whom spoke English. Galle remained the primary training center for the MU for the remainder of the war.

The facilities at Galle were inadequate for the fleet of surface ships that the MU acquired. To provide access to the British repair facility at Trincomalee, the MU prepared a small facility adjacent to the main harbor, known as Dead Man’s Cove. From here the ships of the MU fleet set sail on their various missions to the Arakan Coast, thirteen hundred miles across the Bay of Bengal.

The earliest missions out of Ceylon involved the infiltration of native agents trained at Camp Y. For these missions, the OSS depended on the use of British Royal Navy submarines or Catalina PBY flying boats to carry the agents to the coast of Burma or Indonesia for insertion. Between 1 January 1944 and 23 May 1945, thirty-six missions were run against the coasts of Burma, Thailand, Sumatra, and the North Andaman Islands, half of which used submarines for insertion. The British Navy proved to be willing partners in the various OSS projects, although its shop-worn fleet of submarines often experienced mechanical difficulties in reaching the Burmese coast.

While in support of Operation DURIAN 1, the long haul from Trincomalee across the Bay of Bengal proved too much for the aged HMS Severn. Eighteen hours out of port, the port engine on the submarine died, shortly followed by the refrigeration and air conditioning systems. As a result, the temperature inside the submarine soared, spoiling the ship’s food and roasting the occupants. Stormy conditions on the surface kept the vessel submerged and when it finally arrived in position, three of the four motor launches failed to operate and the fourth capsized. At this point, the captain of the Severn scrubbed the mission and the vessel limped back to Trincomalee.

When missions did not have to be aborted, the common practice of submarines was to surface near the coast. The operational teams positioned the rubber rafts manned by the native agents and their OSS handlers on the forward dive planes. The submarine then dove and held its position offshore until a previously determined rendezvous time when the OSS operatives would return.

During one such mission, Ripley II, as the submarine cruised on the surface a large native prau was sighted. To prevent compromising of the mission, the submarine gave chase and overtook the vessel, which proved to be a fishing boat. The crew was taken into custody and proved to be “five Sumatrans and one large monkey … The five Sumatrans were not intelligent and no information was obtained except that the monkey was trained to pick coconuts and was capable of gathering six hundred in a day.”

The use of the Catalina PBY Flying Boats extended the range and speed of infiltration at the expense of the size of the teams and amount of cargo. By the fall of 1944, the Maritime Unit recognized the need to move its base of operations closer to the Burmese coast and, with this in mind, Pier organized a reconnaissance mission to the Mergui Archipelago, a collection of islands south of Akyab, in September 1944.

Two PBYs from British Special Duty Squadron 628 supplied the aircraft to land an OSS team on Chance Island. Pier accompanied the team comprised of First Lieutenant Gregory Coutopoulis, Second Lieutenant James Fine, and “Chee Chee” the Chinese radio operator. The PBY touched down in a quiet cove at Chance Island and the team cautiously began to prepare the rubber boats for departure. Crewmen armed with submachine guns took up positions on the wings and scanned the shore. The crew prepared to disembark.“ At this time, Lieutenant Fine moved one of the submachine guns in the rubber boat, catching the trigger, with the result that five or six shots were fired before the gun could be freed. Fortunately, the bullets passed under the tail section of the airplane and no harm was done.” After waiting a nervous two hours, the boats were launched and the Catalina flew safely back to Trincomalee.

The displacement across the Bay of Bengal shortened the approaches to the Burma coast and coincided with the advance of the British 15th Corps into Burma. The second Arakan campaign saw the British move south along the coast and eventually overcome the Japanese defenses that blocked the advance. From this point on, the MU depended largely on its own fleet of fast surface boats to insert agents and deliver operational groups to the various islands and coves along the Arakan coast.