NOTE

All photos and patches are part of the author’s collection.

DOWNLOAD

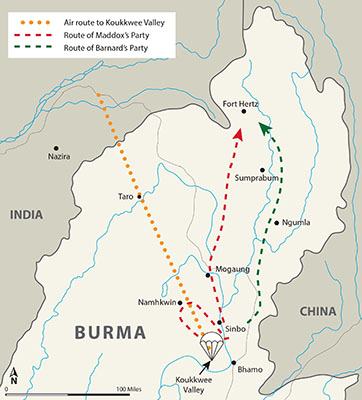

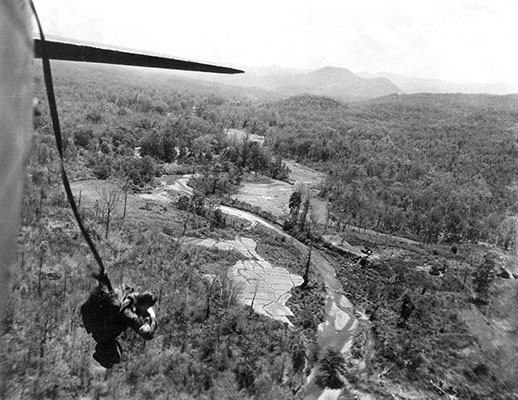

In the lore of Army Special Operations, Detachment 101 of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) has reached near-mythical stature. The Detachment succeeded in racking up an impressive record. By the end of the war, it had been credited with at least 5,500 enemy killed, at the cost of some 200 American and indigenous personnel. However, Detachment 101’s early long-range operations in 1942 and 1943 were largely unsuccessful. These early missions were almost all total disasters. A lack of experience and poor intelligence were ignored by the commanding officer of Detachment 101, Lieutenant Colonel Carl Eifler, in his eagerness to show the value of his organization to Lieutenant General Joseph Stilwell, commanding general of the China-Burma-India (CBI) Theater. The majority of all Detachment 101 failures—agents captured and killed—took place between March and October of 1943. At the end of 1943, only one long-range penetration operation had succeeded out of six overlapping missions. In operations of this type, “failure” equated to the loss of the entire team.

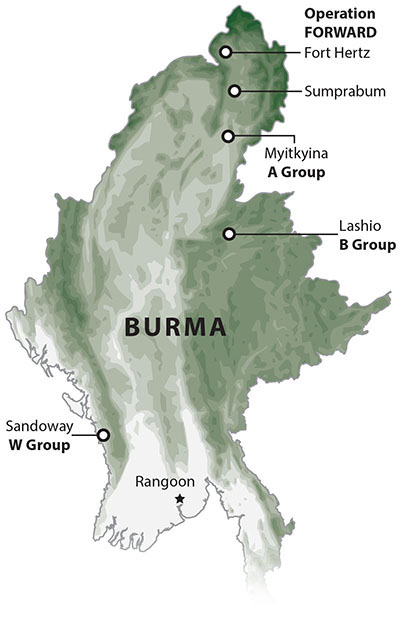

The failed long-range penetration operations in 1943 claimed the lives of more than a dozen agents—Detachment 101’s most valuable assets. Just as in Burma during World War II, Korea in the early 1950s, Vietnam, and Iraq and Afghanistan today, the most valuable commodity in special operations is the highly trained operative. The following article will discuss the first three long-range penetration missions of Detachment 101: “A” Group, “B” Group, and “W” Group. These missions provided some of the earliest operational experiences for the unit. While, with the exception of “A” Group, the others were complete failures, all yielded valuable lessons that determined how future missions would be conducted. These lessons remain applicable now. Burma of 1943 had many of same problems found on America’s battlegrounds today: an unfamiliar operating environment, poor area intelligence with few human intelligence sources, and commanders eager to conduct operations before their units are prepared.

Detachment 101 was formed in early 1942 by the Coordinator of Information (COI), the predecessor of the OSS. General William J. Donovan, the head of the COI and later the OSS, envisioned Detachment 101 as a unit organized and equipped to conduct sabotage behind enemy lines. That its sole mission would be sabotage was anathema for conventional military officers at the time and met much resistance. Many senior Army officers saw little utility in such a unit, and were reluctant to have OSS units operating in their wartime areas. Detachment 101 became the first OSS operational unit in America’s war effort.1 While OSS personnel were operating in North Africa in support of Operation TORCH, they were not engaged in full-scale combat operations. That’s where Detachment 101 was different.2

General Stilwell, however, was more receptive to an OSS presence. In one way, he had little choice. In January 1942, Malaya fell to the Japanese, and the British surrendered Singapore a month later. Having simultaneously occupied Thailand, the Japanese invaded Burma in late January 1942. By May, the Allied forces were in full retreat from Burma. Less than a month after his arrival, Stilwell led his staff out of Burma on foot. Upon reaching India, he declared shamefully, “We got run out of Burma, and it’s humiliating as hell. I think we ought to find out what caused it, go back, and retake Burma.”3 Furthermore, the CBI was not a priority. It was so resource starved that General Stilwell only “commanded” a smattering of American aviation units, and some poorly led and equipped Chinese troops that had been sent to protect the Burma road—the Allied lifeline that supplied China. Not only did he not have any American ground troops, the only Allied intelligence unit in his area of responsibility was the British-led “V-Force” in northern Burma.