FULL SERIES:

Major Bruckner

Part I: SOE France, OSS Burma and China, 10th SFG, SF Instructor, 77th SFG, Laos, and Vietnam

Part II: Pre-WWII–OSS Training 1943

DOWNLOAD

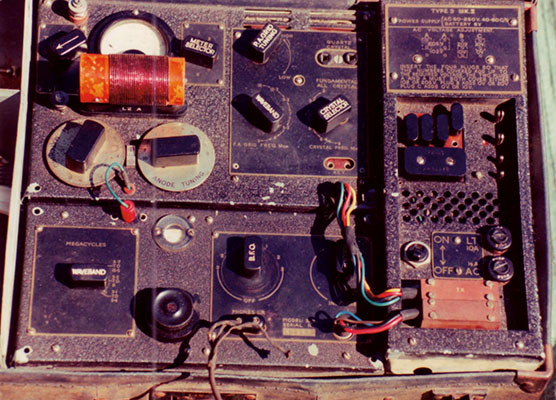

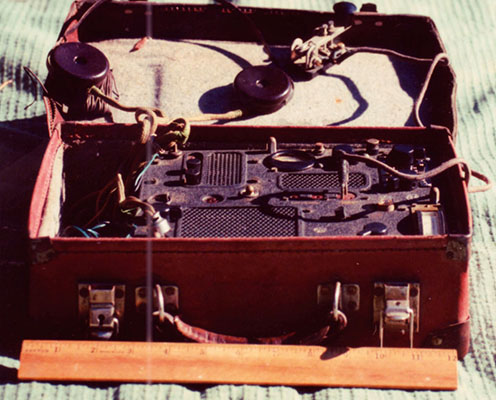

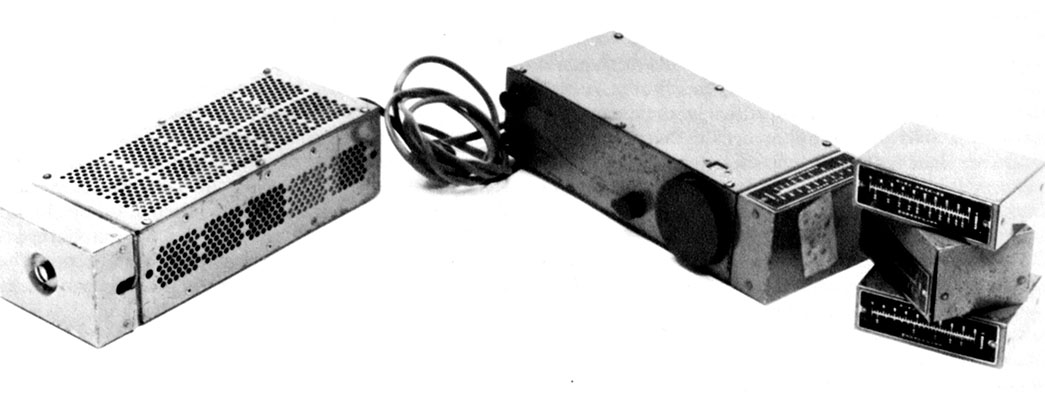

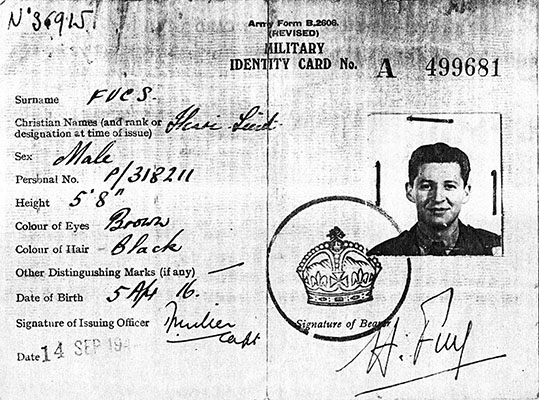

The pre-World War II and Office of Strategic Services (OSS) training experiences of Major Herbert R. Brucker, a pioneer in Special Forces, were discussed in Part II: Pre-WWII–OSS Training 1943. 1 While American-born, he was raised from infancy in the bilingual provinces of Alsace and Lorraine in France. His father brought him back to the United States in 1938. It was 1940 when Brucker joined the U.S. Army. Knowledge of English was not critical for radio operators then because Morse Code (CW) was an international language. Brucker excelled in a skill that was critical in the Army, but more so in the OSS. Technician Four (T/4) Brucker volunteered for “dangerous duty” to escape training cadre duty and his language skills made him a natural to become an OSS special operative. After completing OSS/SO training in the United States, he was detailed to the British Special Operations Executive (SOE).

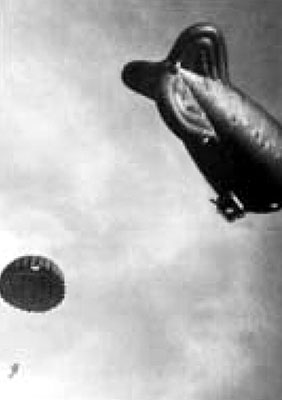

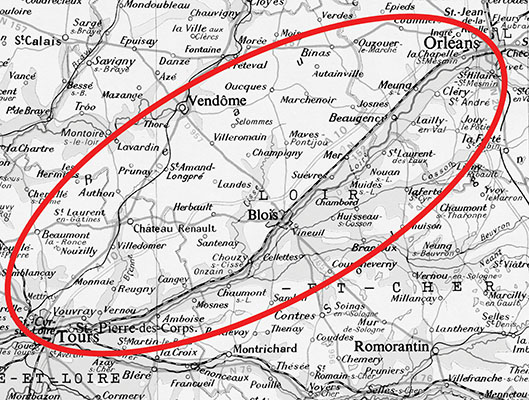

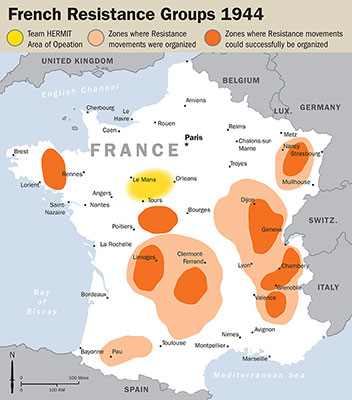

This article chronicles T/4 Herbert Brucker’s SOE training in the United Kingdom and ends with the airborne insertion of “Team HERMIT” into south central France on 27 May 1944. Team HERMIT supported the French Resistance conducting unconventional warfare missions north of the Loire River until mid-September 1944. During those operations in France, Second Lieutenant (2LT) Brucker was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism. After duty with SOE/OSS in Europe, Brucker volunteered to serve in OSS Detachments 101 in Burma and 202 in China. He was a “plank holder” in the 10th Special Forces Group (SFG) with Colonel Aaron Bank (an OSS Jedburgh), served in the 77th SFG, taught clandestine operations in the SF Course, and went to Laos and Vietnam in the early 1960s.2 Brucker’s real special operations training began in January 1944.

British SOE had been putting agents into the German-occupied countries of Europe since 1940. This was almost three years before the United States formed the Office of Strategic Services.3 As such, British field training for special operatives far surpassed anything that the OSS could provide. Colonel Charles Vanderblue, Chief, Special Operations Branch, OSS, knew this because he had detailed one of his training officers, Captain John Tyson, to evaluate SOE instruction. Tyson reported on 30 July 1943: “The training any prospective SO agent has received in our Washington schools prior to his arrival in this theater is entirely inadequate and no trainees should be considered for field operations until they have had further training in this theater, which in many cases will involve a period of three months.”4

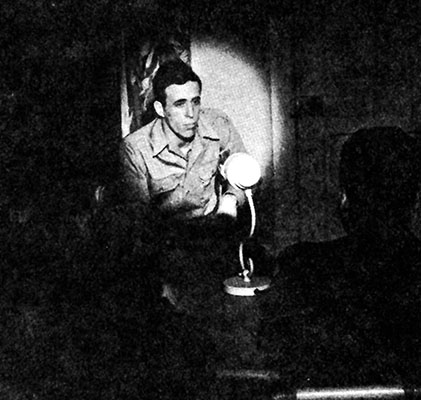

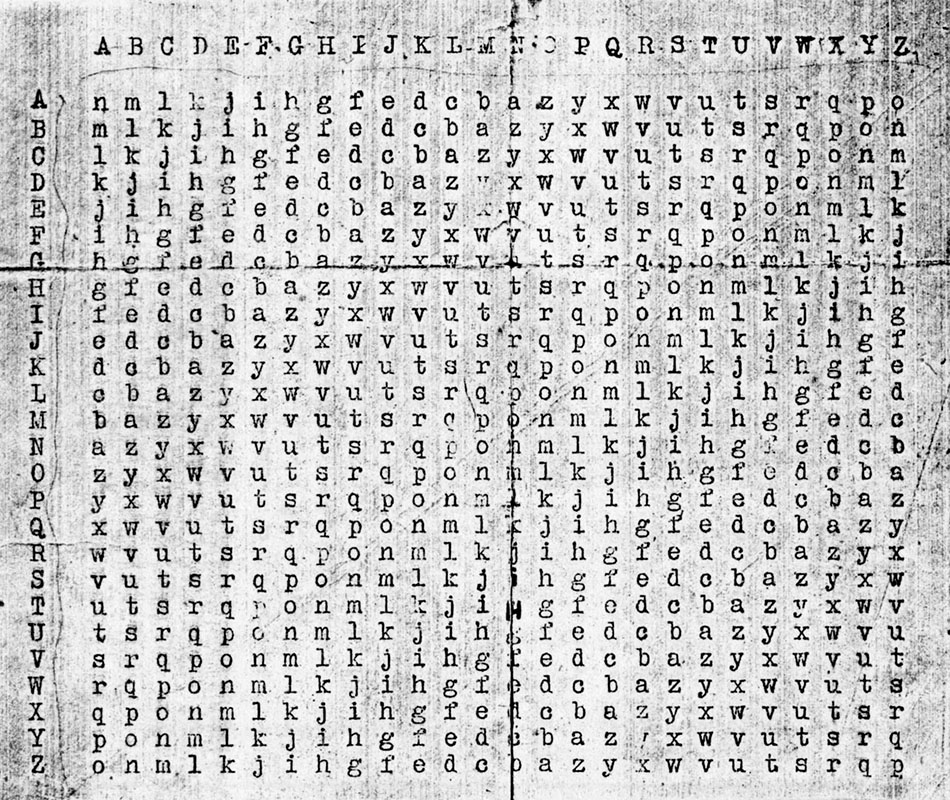

Spread thin by constant operational requirements, the SOE had agreed to joint training and covert activities with the OSS. Highly-proficient bilingual CW radio operators (capable of sending and receiving more than twenty words a minute) were always needed by the SOE. Hence, a trilingual OSS/SO operative (T/4 Brucker) with these radio skills was a real bonus.5

OSS/SO T/4 Brucker, during his SOE training, would be detailed for service with a British special operations team in south central France prior to D-Day, somewhat as a quid pro quo for the joint OSS/SOE arrangement.6 His team, HERMIT, was to replace “PROSPER.” That team had been “rolled up” along with the Resistance network, when their female Hindu radio operator, Noor Inayt Kahn, codenamed “Madelaine,” was captured by the Gestapo in late March 1944. This article will chronicle the SOE training received by T/4 Brucker and his team from January to May 1944 because there are numerous similarities with Special Forces assessment, qualification (“Q” Course), specialty, and advanced skills courses today. Unknown to Brucker at the time, the SOE training was specifically tailored for the HERMIT mission team members.

Traveling in uniform from Washington to New York, T/4 Herbert R. Brucker, the newly-minted Special Operations (SO) operative “E-54,” was accompanied by another OSS soldier. There, Brucker and his escort, Andre, boarded a troop carrier (a former Australian cattle boat) bound for England. “When we got aboard that night, the vessel was virtually empty. The city was supposedly under ‘brownout’ conditions, but I remember a large red neon Coca-Cola sign blinking away in the night. Troops were billeted from the bottom to the top deck and from the rear to the front. Naturally, since we got on first, we ended up in the bottom rear. I grabbed a lower bunk and went to sleep. When a lot of noise woke me up in the morning, I realized that I was above the propeller,” said Brucker.7

“We were underway and there were troops jam-packed everywhere. All of the triple-stacked bunk beds were filled with men. I was issued a cork lifebelt, but where I was bunked, I didn’t have a chance if we got torpedoed. There was only one stairway to the deck in my section. Besides, we never practiced lifeboat drills,” mused Brucker. “We were in a convoy and the boat zig-zagged back and forth.”8 The dining area for the enlisted on the ship was so small (capacity for fifty) that meals were served twenty-four hours a day. Each soldier received a colored card that indicated his eating shift. Food was served in buckets (boiled potatoes filled one, beef stew another, and bread a third). Soldiers doled out what they wanted. Whoever emptied a bucket had to get it refilled. “The meals were very simple, but there was plenty because a lot of guys were seasick. The North Atlantic in winter was rough. For those ‘hugging their bunks’ in the bay, five dollars for a ‘K-ration’ meal was a good deal,” said Brucker.9

Life aboard the cattle boat was crude. There was one latrine on each deck. That was the only place where smoking was permitted. “An MP limited access; one man out … one man in. It was always packed. Once inside you stumbled about in a thick cloud of cigarette smoke that reeked of human waste and vomit. It was terrible. Despite the cold of winter (mid-December 1943), some soldiers slept on deck because it was so hot in the crowded bays below and they figured that they could jump overboard if torpedoed. They wouldn’t have lasted ten minutes in the cold water. It was a big relief when we finally docked at Glasgow, Scotland, on 23 December 1943,” remembered the OSS operative.10

Once ashore, T/4 Brucker and Andre, his OSS escort, boarded a troop train for London with railway cars that were half the size of American ones. When the train arrived in London, “blackout” was in effect. Brucker recalled that “it was pitch black outside … so dark that you couldn’t see the man in front of you. We were formed into ‘chain gangs’ and marched to the U.S. Army Replacement Center (‘Repo Depot’ in soldier parlance). We dropped our duffle bags in an assigned room. Outside we formed another ‘chain gang’ and shuffled off in the dark to a messhall. ‘Blackout’ in London made the ‘brownout’ in New York ridiculous.”11

The two OSSers discovered that the war was real the next morning. Both men were awed by the devastation caused by the Luftwaffe bombing “blitz” of London each night. Once T/4 Brucker had been in-processed at the Repo Depot, Andre disappeared. The day after Christmas 1943, Brucker was picked up by car and taken to a headquarters in London. There, he was informed that he would be attending SOE training and to report back on 2 January. “That came as a shock. I had already been trained by the OSS. I felt that I was ready for combat.”12

No one in Washington, including his OSS/SO handler, George F. Ingersoll, had ever explained why he was being sent to England, nor that Brucker was going to be detailed to the British SOE. When he protested to the Director of F-Section (France), Major Maurice J. Buckmaster replied that “it would simply be murder to send you on an operation with just OSS training.”13 Brucker was one of sixty-five Americans waiting to attend SOE schools at the end of 1943.14 Later, he had to admit that “SOE training was far superior. It made most of my OSS/SO stateside training seem amateurish.”15 Not happy to undergo more schooling, Brucker, the professional soldier, did as he was ordered.

Initial SOE training, like Special Forces assessment and selection, was to determine the physical conditioning and psychological suitability of candidates. This was accomplished at STS 7 (Special Training School 7) near Pemberley, twenty miles to the west of London. Activities were sometimes done singly and other times in teams, but obstacle courses were used regularly. “Since we were a ‘mixed bag of nationalities’ having different levels of English language skills, you had to quickly determine physical abilities and agree on a leader. The instructors were always looking for those with initiative, risk takers, and clever innovators,” remembered Brucker.16 They assessed how the physical obstacles were tackled, how problems or puzzles were solved, and the number of details remembered during memory tests (maps, pictures, photos, critical steps of a process, or after reading instructions). Stress was a constant companion. “‘Hurry up! Do something!’ were regular commands of the instructors. The trainees never got feedback. So, Brucker did his best all the time.”17

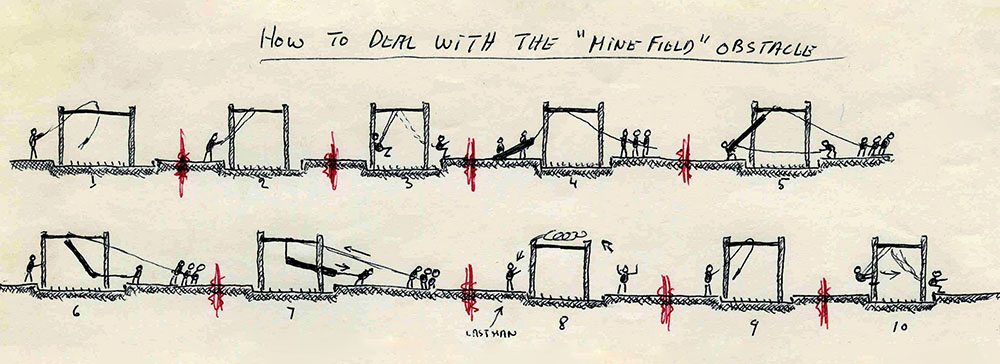

“Speed was not necessarily critical. It was how you solved the challenges. I failed the barbed wire and minefield obstacle because I crawled under the wire and tried to wiggle around the mines. I found out later from a buddy that the best solution was to walk across using the barbed wire stakes,” said Brucker. “Often numerical values were assigned to an obstacle and success was measured by how fast you or your team could get fifty points. Tough ones might be worth twenty-five points each, while simpler ones would have less value. You had to calculate how to meet the standard before your agility waned and strength failed.”18 The team problem solving tests were much like those encountered in Army Leader Reaction Courses in Basic Non-Commissioned Officer Courses (BNCOC) and SF assessment and selection. After the psychological and physical evaluations, Brucker returned to London.

In the British capital, Brucker lived in an attic room of a private boarding house for the elderly. During air raids, he slid his blackout curtains aside to get a panoramic view of the bombing. Then, he would hear “the anti-aircraft ack-ack gun shrapnel tinkling down on the roof like sleet.”19 His “control” headquarters was in the top floor suite of an old, fancy hotel. “This was the routine,” Brucker explained. “You knocked on the door. A peephole was opened (like a ‘Roaring 20s speakeasy’) by Herbert, the security guard. The female receptionist, sitting at a desk in the center of a living room, checked the list of trainees. She told you to go to a particular room for a meeting, or gave you your next assignment with specific instructions.”20

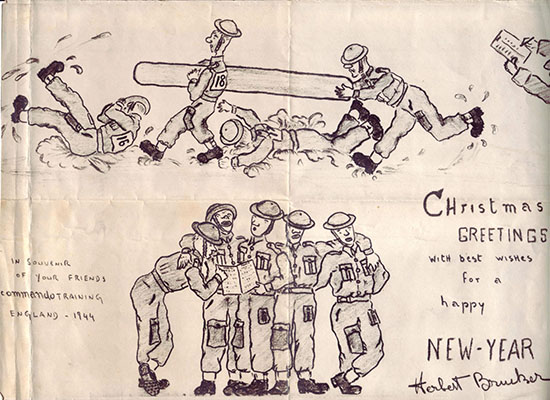

T/4 Brucker, in his U.S. Army uniform, joined a group of American servicemen and a British officer at the Pennington train station to go to para-military training (STS 21–25) in northern Scotland. A British “conducting officer” accompanied all trainee groups. Since he went through all training, this officer was an evaluator as well.21 The group was housed at a hunting estate in Inverness-shire. British battle dress uniforms were worn during basic commando training. “The weather was miserable … cold and foggy. Midway through the course we were assigned a sabotage mission and provided a map. All twelve of us had a specific task and we had to prepare plans of action and brief them to the others. Then, a few days later, the instructor chose the team leader and we had to execute the mission without notes or doing a rehearsal. Once done, our ‘commando’ was critiqued. The mission was repeated until accomplished successfully,” recalled Brucker.22 At Aberdeen, Scotland, the northwest railway terminus, his group was taught to “drive”—start and stop—a steam locomotive and how to place explosives on the railway tracks to insure that it derailed.