DOWNLOAD

Early in World War II, the successful use of airborne forces by Germany shocked the world. The Germans used their glider-borne forces in the assault of the “impregnable” Belgian fortress Eben-Emael on 10–11 May 1940, and they combined parachutists with gliders when they invaded Crete in May 1941. These events prompted greater American military interest in airborne forces and the use of combat gliders. By 1942, the U.S. Army Air Corps had a prototype that would later become the American workhorse of World War II. The CG-4A Waco had a wingspan of eighty-four feet, a length of forty-nine feet, and could carry 3,750 pounds.1

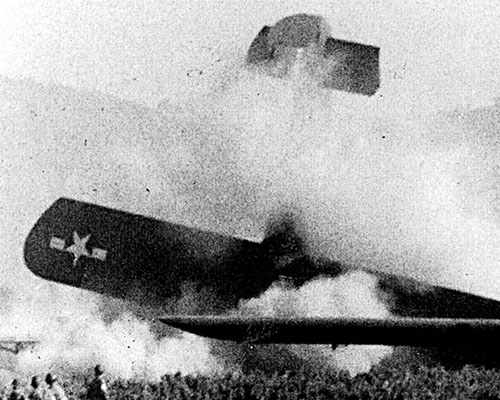

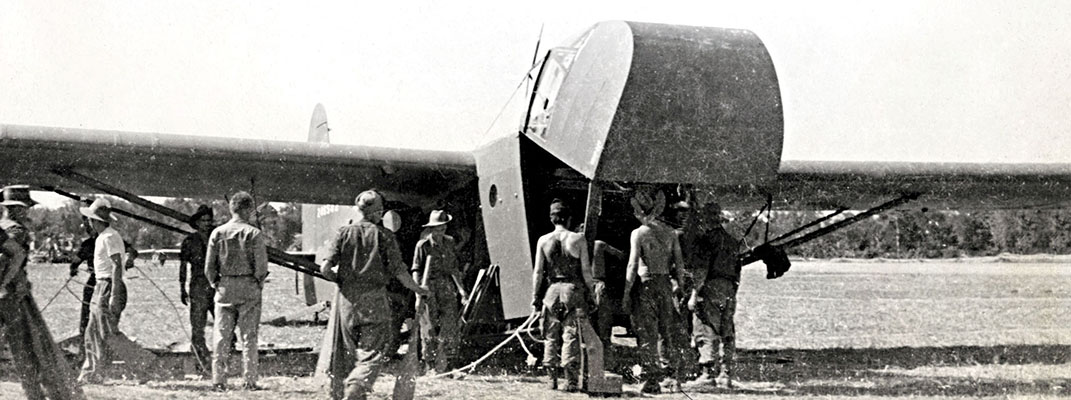

It was constructed of plywood and canvas stretched over a tubular steel frame. A C-46 or a C-47 cargo aircraft could tow it. The CG-4A had a crew of two. The standard combat troop load was thirteen glidermen. If heavier equipment was transported, the interior of the CG-4A could be modified to carry a combination of glidermen, a jeep, a loaded jeep trailer, light truck, miniature bulldozer, 75mm pack howitzer, or a light anti-tank gun. The cargo was loaded through the CG-4A’s nose section which could be flipped up to allow access. Nearly 14,000 CG-4As were built at an average cost of $18,800. In a combat environment, the often heavy damage they suffered and the air assets required for retrieval caused them to be regarded as disposable.2

Flying in them was a unique experience. Ned Roberts, a writer for the United Press, described his experience during a demonstration glider flight: “Under tow … we found gliding to be much like riding in a transport. The wind’s roar, as the transport pulled us through the air at close to 150 miles an hour, made fully as much noise as the plane’s engines. At 2,000 feet, they cut us loose, and the Dallas Kid [the name of his glider] promptly bounced straight up for 400 feet. That’s when I lost my stomach … Through the transparent nose of the Dallas Kid, we could see the air base and surrounding cotton patches [below] spinning around like a huge pinwheel.”3 The evasive maneuvers associated with a combat flight would have made the ride that much more harrowing, especially when the pilots were “fighting” for open spaces to land.