DOWNLOAD

After Inch’on and the Eighth U.S. Army (EUSA) breakout from the Pusan Perimeter, the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) reeled back in shambles, their supply lines cut. On paper, the NKPA had a total of eight corps, thirty divisions, and several brigades, but in reality most were combat ineffective.1 Many North Korean units had fled north of the Yalu into Manchuria in order to refit and replenish their numbers. Only the IV Corps with one division and two brigades opposed the South Korean I Corps in northeastern Korea, and four cut-off divisions of II Corps and stragglers resorted to guerrilla operations near the 38th Parallel.

With the war appearing won, only the Chinese and Soviet response to the potential Korean unification under a democratic flag worried U.S. policymakers. Communist China was the major concern. Having just defeated the Nationalist Chinese and reunified the mainland, the seasoned Red Army was five million strong. In fact, some of the best soldiers in the Chinese Communist Army were among those “volunteers” who intervened early in the Korean War.2 When the stream of Chinese “volunteers” became a flood, Allied optimism for a quick end of the war vanished despite much improved capabilities since July 1950.

Four Months Into War: The Allied Order of Battle: November 1950

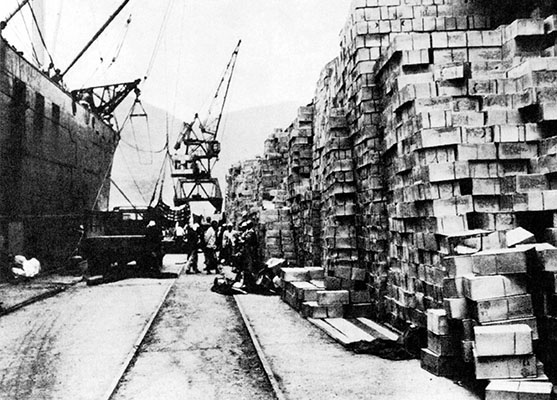

Surprised by the North Korean attack on 25 July 1950, the Allies lost no time in building a larger and more capable force to counter the Communist aggression. By 23 November 1950, the Allies had massed 553,000 troops (the majority of whom were American and South Korean); counting 55,000 air force and 75,000 naval personnel.3 UN members also contributed forces.

On 7 July 1950, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 84, condemning North Korean aggression. Resolution 84 authorized member states to furnish military forces under a U.S.-led UN Command to help restore the balance. Fortunately for the United States, the Soviet Union, a permanent Security Council member with veto power, boycotted the UN because the Republic of China and not the (Communist) People’s Republic of China, held a permanent seat on the Council. Ground forces came from the United Kingdom (11,186), Turkey (5,051), the Philippines (1,349), Thailand (1,181), Australia (1,002), The Netherlands (636), and India (326). Sweden furnished a civilian medical contingent (168). France contributed an eleven hundred-man battalion that arrived at the end of November. Air forces from the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, and South Africa, quickly responded as did naval forces from the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, France, New Zealand, The Netherlands, Colombia, and Thailand.4

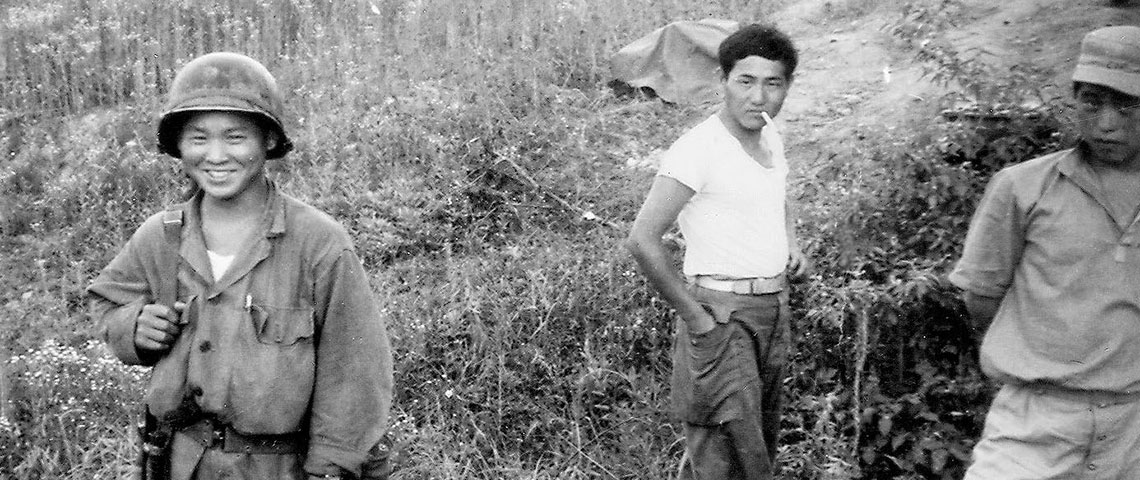

From the four divisions committed by August 1950, Washington’s response grew exponentially. All services rushed units into theater to participate in General (GEN) Douglas A. MacArthur’s offensive to free the south from Communist domination. To increase the combat power of the weakened U.S. infantry divisions, South Korea provided as many as 8,300 KATUSAs (Korean Augmentation to the United States Army) to most American divisions.

The Eighth U.S. Army (EUSA), led by Lieutenant General Walton H. Walker, and the X Corps, commanded by Major General Edward M. Almond, were the two major U.S. ground combat commands in Korea in late 1950. EUSA had two Corps (I and IX), four divisions (1st Cavalry, and the 2nd, 24th, and 25th Infantry divisions), the separate 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team, and an EUSA Ranger company (see Eugene Piasecki’s Eighth Army Rangers: First In Korea). Most of the Republic of Korea Army (ROKA) served under EUSA control; two corps (II and III) with eight divisions (1st, 2nd, 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, and 11th). Several UN contingents also bolstered EUSA, including the 1st Turkish Armed Forces Command, the 27th British Commonwealth Infantry Brigade (with Australian and Indian troops attached), the 29th British Independent Brigade Group, the Thai 21st Regimental Combat Team, and the battalion-sized Netherlands Detachment, and the Philippine 10th Battalion Combat Team.5