DOWNLOAD

The sudden North Korean invasion of South Korea in June 1950 caught the United States Army unprepared for war and revealed the extent to which the post-World War II drawdown had impaired its ability to conduct special operations. In the previous issue of Veritas (6-1), the focus was on the number of ad hoc special operations units fielded by the Far East Command (FECOM) and a U.S. infantry division in an effort to stem North Korean advances in the early days of the war. The GHQ Raiders, Eighth Army Rangers, the Ivanhoe Security Force, and the “Shake and Bake” Civil Assistance teams at P’yongyang and Chinnamp’o were units hastily put together to address specific missions that could not otherwise be filled by the Department of the Army in the United States.1 After the successful defense of the Pusan Perimeter blunted the North Korean offensive, the landing at Inch’on turned the tide of battle against the Communists. From that point, the Army addressed the deficiencies in its special operations forces in a more deliberate manner.

In the late summer of 1950, the Army worked to rebuild one capability deemed necessary for success on the Korean battlefield; the ability to stage raids behind enemy lines. Army Chief of Staff General (GEN) J. Lawton Collins directed that “Marauder” units be formed to counter North Korean guerrilla success on the battlefield. This issue of Veritas will address the rebirth of Army-trained Ranger units and the training conducted to handle that large, complex mission.

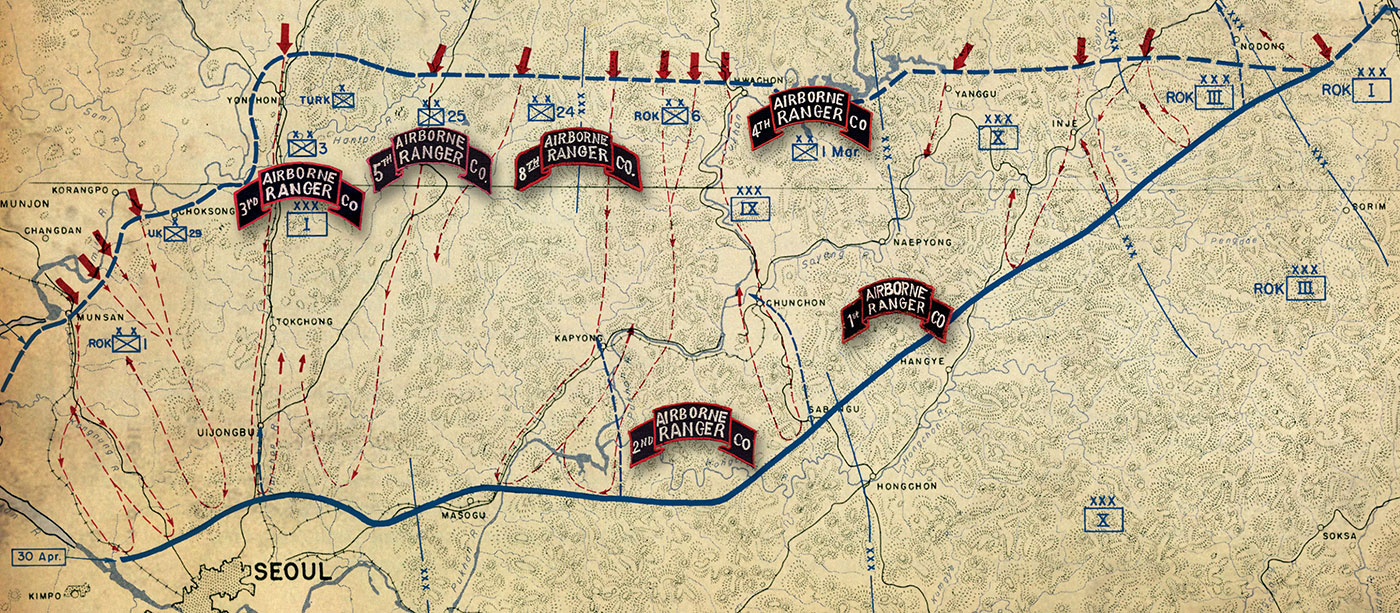

In August 1945, the Army’s six Ranger battalions were disbanded in the postwar draw down. Ranger units were resurrected during the Korean War, this time as airborne companies for attachment to conventional U.S. Army infantry divisions. In their brief fourteen-month tenure, the six Ranger Infantry Companies (Airborne) sent to Korea fought in numerous engagements and gained a reputation for fighting prowess just like their WWII predecessors. This issue provides the background on the formation and training of the Ranger Companies that deployed to Korea. One major article examines in detail the experiences of the 2nd and 4th Companies from their organization through the airborne operation at Munsan-ni. Additional articles highlight significant missions by each of the six companies. It concludes with a summary that documents the effectiveness of the Rangers and explains the reasons behind their disbanding. While their existence was brief, their outstanding combat performance contributed significantly to the history of today’s 75th Ranger Regiment.

“One of the major lessons to be learned from the Korean fighting appears to be the fact that the North Koreans have made very successful use of small groups ... for the specific purpose of infiltrating our lines ... ” — General J. Lawton Collins

The U.S. Army Ranger Infantry Companies (Airborne) were formed in response to the long-standing successes by North Korean guerrilla units that disrupted operations in the Allied rear areas in the early stages of the war. As the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) drove the U.S. and Republic of Korea Army (ROKA) forces south, they managed to insert sizeable guerrilla units behind the retreating allies. Between two and three thousand guerrillas infiltrated the Ulchin area when the NKPA pushed south from Wonju in July 1950. A guerrilla element of similar size stepped ashore on the east coast and made its way inland to establish strongholds in the Taebaek Mountains. The ROKA was compelled to move two special anti-guerrilla units, the 1st Separate Battalion and the Yongdongp’o Separate Battalion, from the southwest across the peninsula to counteract enemy success behind the lines.3 The effectiveness of these guerrilla units was not lost on the U.S. Army.

On 29 August 1950, GEN J. Lawton Collins, issued a memorandum directing the establishment of experimental “Marauder” companies to deal with the guerrilla threat:

“One of the major lessons to be learned from the Korean fighting appears to be the fact that the North Koreans have made very successful use of small groups, trained, armed and equipped for the specific purpose of infiltrating our lines and attacking command posts and artillery positions. ... The results obtained from such units warrant specific action to develop such units in the American Army.”4

Collins’ memorandum directed that Army Field Forces, the proponent for training, establish a training section at the Infantry Center at Fort Benning, Georgia, prepare a table of organization and equipment (TO&E), and conduct the organization, training and testing, to include combat, of an experimental unit. The training facility was to be established and staffed to train the first volunteers by 1 October 1950. It was at the initial planning conference on 6 September 1950, convened by Major General (MG) Charles L. Bolte, the Army G-3, that the name Rangers was adopted for the new units.5 The execution of GEN Collins’ directive for the all-volunteer Ranger companies proceeded at a break-neck pace.

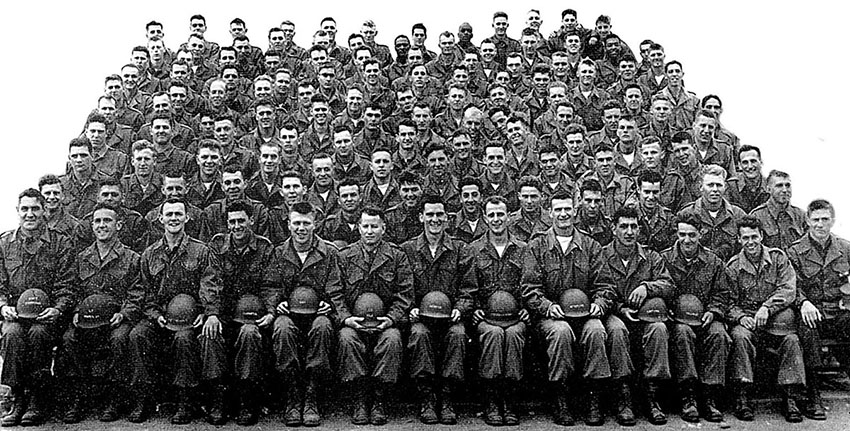

GEN Collins selected veteran World War II infantry regimental commander Colonel (COL) John G. Van Houten, to assemble and train the Ranger companies. His deputy was COL Edwin A. Walker, former commander of the WWII First Special Service Force.6 On 15 September 1950, they formed the Ranger Training Center at the U.S. Army Infantry Center at Fort Benning, GA.7 A training cadre of twenty-three officers and thirty-four enlisted men was in place by 23 September 1950. A provisional Table of Organization and Equipment, (TO&E) was soon developed. TO&E 7-87 (16 Oct 1950) set the Ranger Company manning at 5 officers and 107 enlisted, with an allowable 10% combat overage bringing the company strength to 122.8 A standard infantry rifle company of the time had a TO&E strength of 211.9 The first cycle was set up to accommodate four companies in training. They were numbered 1 thru 4. Unlike their World War II predecessors, the first Ranger Infantry companies were airborne units. The initial three hundred volunteers began arriving in late September and the training of the first three companies (1st, 2nd and 3rd), began on 2 October 1950.10 The 4th Company, comprised of black soldiers, was organized on 6 October and began training on 9 October 1950.11 The first six-week training program was to be completed in November. The 1st Ranger Company deployed to Korea arriving on 9 December 1950.12

The first training cycle curriculum consisted of seventeen different topics that included training with foreign weapons, demolitions, field craft and patrolling, map reading, escape and evasion, and intelligence collection.13 Demanding physical and close quarters combat training were an integral part of the daily training, and were key to weeding out those who could not meet Van Houten’s high standards. By mid-October 1950, the first four companies had progressed to the point that they were combat ready.

On 19 October 1950, the Army G-3 requested approval from GEN Collins to deploy three of the Ranger companies to Korea. Collins, in keeping with his original intent, authorized the deployment of one company (1st) to FECOM, but slated two (the 2nd and 4th), for Europe. The 3rd Ranger Company remained at Fort Benning to assist in training four more Ranger companies for deployment to Korea in January 1951.14 It was the acceptance by GEN MacArthur that Communist China had entered the war in force in early November that caused him to request all available U.S. forces. In response, the Army redirected the 2nd and 4th Companies from Europe to Korea.15 The two Ranger companies deployed together and arrived on 24 December 1950.16

When the 1st Ranger Company arrived in early December, it was attached to the 2nd Infantry Division, Eighth Army (EUSA). The 2nd Company was sent to the 7th Infantry Division, X Corps, and the 4th Company went to the 1st Cavalry Division, EUSA. The 3rd Company at Fort Benning acted as cadre for the newly formed 5th, 6th, 7th, and 8th Companies. After completing the original six-week training program, the 3rd joined the 5th and 8th Companies for an additional three weeks of mountain and winter warfare training at Fort Carson, Colorado, before going to Korea.17 The 6th Ranger Company went to Europe in 1951 and was attached to the 8th Infantry Division. The 7th Company assumed the cadre role at Fort Benning to train more Ranger companies.

The six Ranger companies in Korea engaged in some of the most grueling fighting of the first year of the war. But by mid-1951, when the front lines had stabilized roughly along the original 38th Parallel, missions for which the Rangers were best suited, notably raids behind enemy lines, were no longer feasible. At this point, FECOM disbanded the Ranger companies in theater, assigning the majority of the men to the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team and the infantry divisions in country.18

By October 1951, all of the Army’s Ranger Companies had been disbanded. At Fort Benning, the Ranger Training Center, became the Ranger Training Command, and began to train individuals instead of units. Then, the Ranger Department of the Infantry School conducted the Army Ranger Course. The training curriculum originally developed for the Korean War Ranger companies became the foundation of the Army’s premier light infantry and leadership course, the Army Ranger School.