… a number of remote little islands in the Yellow Sea, unnoticed before … suddenly had become laststand strongholds of North Korean antagonists to the Communist regime.”1

DOWNLOAD

The sudden reversal of fortunes brought on by the allied amphibious operation at Inch’on in September 1950 did not go unnoticed by North Korean citizens, particularly those who had long opposed Communist rule. Now in shambles, the once-powerful North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) retreated rapidly to the north to escape pursuing United Nations (UN) forces. In October 1950, longtime anti-Communist rebel Kim Chang Song listened to the sounds of approaching artillery and contemplated ways to seize control of his village. From their hidden camp in the rugged mountains, Kim and his like-minded neighbors planned attacks against the Communist Party members, North Korean police, and the local militia troops that had taxed and persecuted them for the past five years.2

Earlier, Kim’s band had stolen five North Korean military uniforms, some weapons, and ammunition. Disguised as soldiers the small group set up a roadblock and ambushed an NKPA vehicle, killing the enemy soldiers before they could react. The truck yielded a treasure: 108 well-used Russian rifles with ammunition that Kim quickly distributed to his other partisans. He also provided them with detailed plans for a coordinated attack on multiple enemy positions to commence at 0900 hours on 13 October. Once those actions were finished, Kim’s guerrillas focused on larger targets. By noon on 15 October Kim’s ad hoc band had rid their township of every Communist soldier, policeman, and Party member, proudly restoring freedom to the area for the first time since September 1945.3 Although the size of the resistance movement varied from place to place, in areas like Kim’s Hwanghae Province the groups achieved significant results for a short period of time.

What circumstances could compel tens of thousands of North Koreans to risk everything and fight alongside Americans against the Communist forces during the Korean War? This article argues that some elements of the North Korean population resisted Communism between 1945 and 1950, and that their opposition established a nascent resistance movement before the war began. In many cases, these early protesters became the leaders for the several community-based paramilitary groups that fought to rid their townships and districts of Communist influence when the North Korean government was most vulnerable. These irregulars continued to engage their enemy when the military situation again favored the NKPA when the Chinese intervened. The article focuses on the key events between 1945 and 1950 that produced the guerrilla forces of 1951 through 1953: how Korea was divided following the surrender of Japan to the Allies, how changing social and political conditions within the North generated dissent, and how the gradual tightening of Communist control over North Koreans after 1945 helped spawn a grass roots resistance movement that fought to free its members from a repressive regime. It also details how the changing tides of the Korean War affected those partisans who continued to fight Communism.

The Allied victory over Japan in August 1945 ended World War II, yet left hundreds of thousands of Japanese soldiers still occupying large portions of mainland Asia, from China to Burma. The sheer scale of the task of disarming them and reestablishing local government functions over such a wide expanse challenged American military and political planners. To complicate matters, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), by declaring war against Japan on 8 August 1945, insisted on being involved in the disarmament process.4 Although there would be no combined occupation and administration of Japan as there had been in Germany, it became practically impossible to keep the USSR out of postwar reconstruction efforts in Asia. And, after its last-minute invasion of neighboring China’s industry and resource-rich Manchurian Province in early August, the Soviets used their disarming of Japanese troops in North Korea as a toehold to influence events there, further insisting on taking part in that country’s restoration to sovereignty, preferably under Communist leadership.

At that time, North Korea held most of the industrial capacity and power generation capability in the peninsula, thereby making it a prize to whomever controlled that region. Additionally, because the USSR shared a common boundary with Korea, Soviet leaders considered that region to have strategic significance as a buffer from the West.5 Complicating Korea’s internal governmental restoration was the fact that it had been administered as a Japanese dependency since 1910. Because of their association with the hated Japanese, most Korean citizens were distrustful of the native Korean civil servants and believed they needed to be replaced by persons not tainted by colonialism.6 The Soviet occupiers exploited this point to their advantage.

In an effort to resolve the problems of restoring sovereignty to the Korean people, the United States and the Soviet Union agreed to a temporary division of the peninsula along the 38th Parallel: the U.S. would disarm Japanese troops south of that arbitrarily designated line, while the Soviets did the same for Korea north of it.7 Although never intended to serve as a functional boundary between two sovereign entities, Soviet intransigence about creating a friendly buffer state linked to industrial and mineral production in the USSR led to installing a Communist government in North Korea. Meanwhile, the United States, United Kingdom (UK), and the United Nations’ newly created Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK) supported a democratic government in the south.8 The conditions were set for a clash of ideological differences between the two Korean states.

Following UN-supervised elections in the south and the establishment of the Republic of Korea (ROK) on 15 August 1948 under President Syngman Rhee, most American forces departed. They left behind a small Provisional Military Advisory Group (PMAG) of only one hundred soldiers to train the new nation’s lightly armed military. With U.S. national interests focused more on demobilization and disarmament after its victory in the World War, PMAG personnel focused their efforts on training and equipping a small constabulary force to serve as the ROK Army. By design, the ROK’s military had no tanks, no offensive aircraft, only light artillery and little anti-air capability.9 In the north, however, increasingly authoritarian and aggressive Communist rule took hold and its military developed along quite different lines.

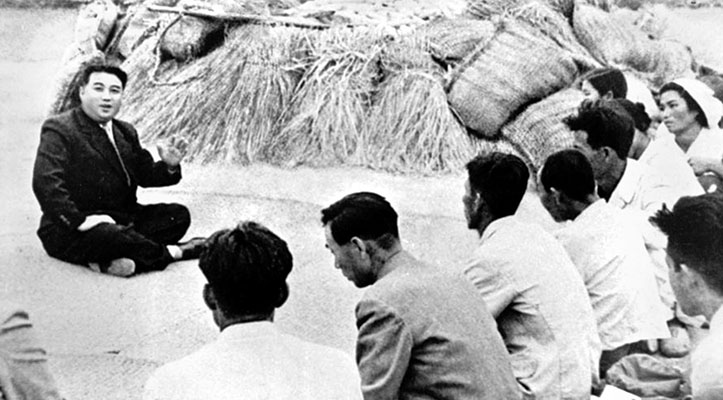

With the full support and assistance of the USSR, new Communist-trained North Korean leaders like Kim Il Sung instituted radical changes designed to strengthen their military power and tighten the dominant Communist Party’s grip on the population. Large quantities of Soviet military equipment, supplies, and advisers poured in, and tens of thousands of Koreans who had fought alongside Mao Zedong’s Red Army in China constituted the combat-hardened core of the powerful NKPA. With Soviet backing and prompting, Kim Il Sung and other contenders for power began implementing Communist policies that had already proven effective in Eastern Europe. On 5 March 1946 Kim’s Provisional People’s Committee passed a Land Reform Act that “completely dissolved” the traditional Korean ruling class, the landowners and local governing officials, and placed them at the mercy of peasant farmers.10

That legislation constituted the first step of a social restructuring within the north and the initial phase in the later forming of collective farms. Increased agricultural ‘taxes’ and inflated assessments then tied the rural farmers to support of government policies by forcing them to pay up to 70 percent of their crops to the government. Furthermore, in 1947, nationalization placed “over 90 percent of industry’s 1,034 important factories and businesses” under direct control of the government. A succession of national conscription acts then inducted most young men into either the highly regimented NKPA or in forced labor projects. Religious organizations and oppositional political parties were persecuted through widespread extra-judicial jailing or executing of anti-Communist or pro-democracy leaders and supporters. All of these policies elevated trusted Korean peasants to positions of authority while demeaning the educated and/or skilled middle and upper-classes. As power began to concentrate around charismatic Koreans like Kim Il Sung, they employed their popularity to further purge rivals, punish protesters, and hold tightly the reins of power.11

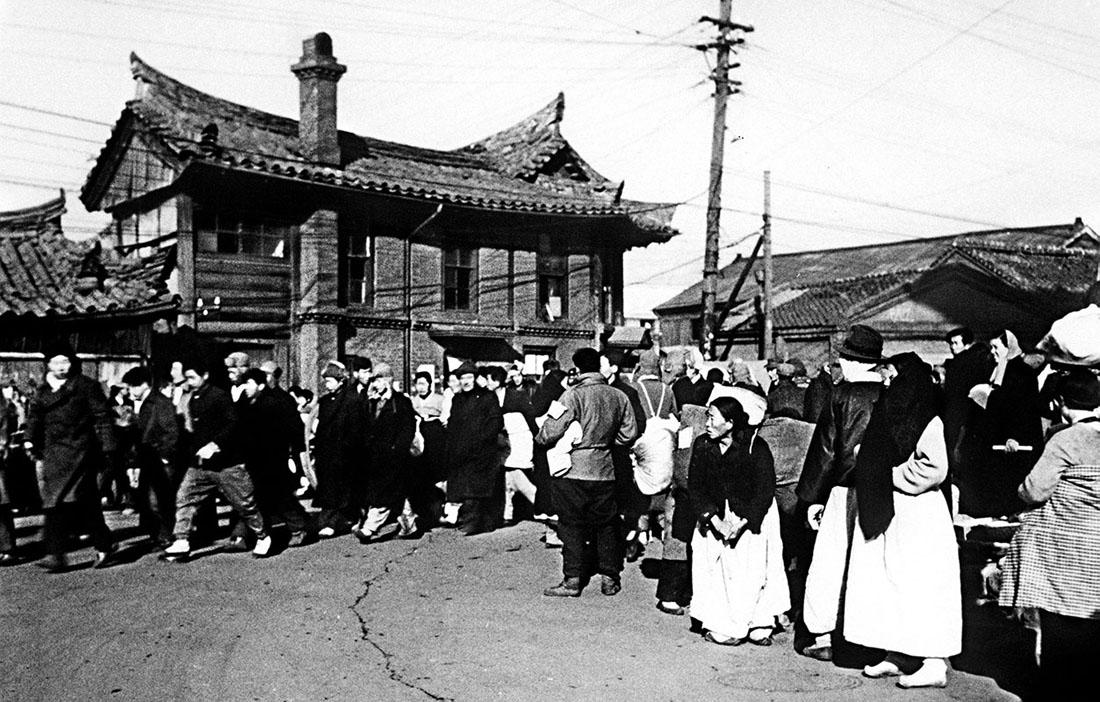

The North Korean government harshly suppressed dissent and further tightened controls over its citizens. These measures in turn prompted some to challenge governmental authority. The more the Communists clamped down, the more these dissenters pushed back. Millions ‘voted with their feet.’ One American official reported that “Russian Occupation is forcing thousands of Koreans and Japanese to flee southward toward the American zone.”12 By “allowing the exodus of those who opposed Soviet occupation policies (primarily large landowners, Christians, and Koreans who had collaborated with the Japanese) [this simplified] the process of establishing political control” in North Korea, even though the resultant ‘brain drain’ reduced the numbers of skilled persons.13

However, not everyone who stayed complied with the escalating authoritarianism of the Communist government; many refused to leave and decided instead to resist. Some viewed the imposition of Communist ideals as another form of foreign influence in Korean affairs, like the despised Japanese occupation.14 The Soviet presence in Korea only reinforced that perception. In some of the more remote regions of the north, anti-Communist movements formed around religious, educational, and trade organizations. And the more the groups resisted, the harder the local Communist leaders cracked down causing a vicious cycle of oppression. Some of the more hardened protesters and draft evaders fled to the remote, rugged mountains to avoid arrest, imprisonment, or injury.15 Pak Choll, a future guerrilla leader, “kept up [his] anti-Communist uprisings and was put in jail for 3-1/2 months,” causing him to be more clandestine in his activities afterward.16 A small core of resisters took a more direct approach by physically attacking tax collectors, police, government officials, and draft enforcers. These early anti-Communist resistance elements became the heart of the guerrilla organizations that would later fight under the United Nations flag.

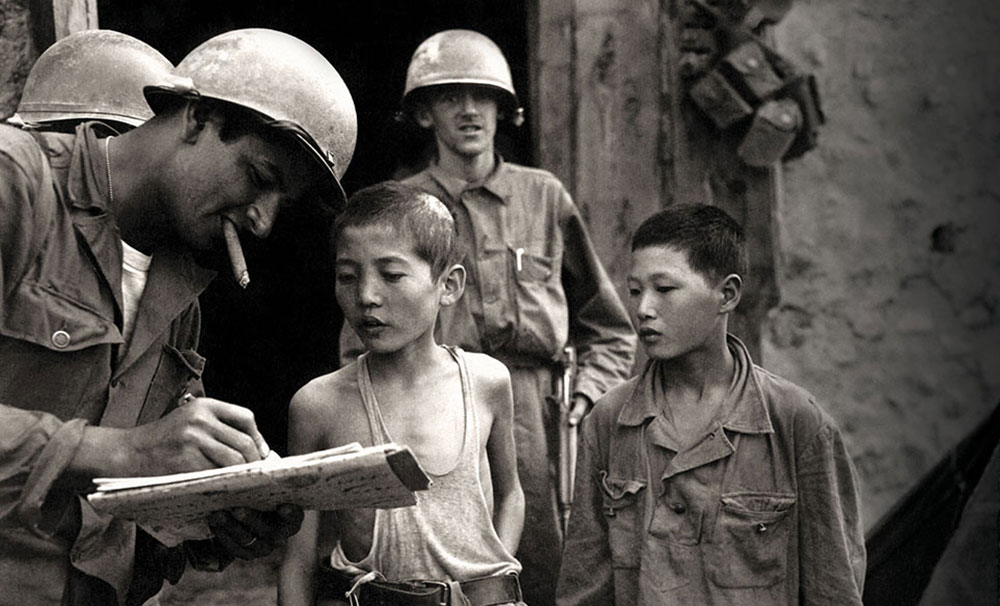

The sudden surge of the NKPA’s full-scale assault on the south in the wake of Kim Il Sung’s invasion on 25 June 1950 left Communist officials in rural areas without the full protection of military forces. By the end of September, with the NKPA in full retreat as a result of General (GEN) Douglas A. MacArthur’s decisive amphibious assault at Inch’on and the breakout of UN forces from Pusan, many opponents of Communism believed that an opportunity to take action had arrived. In areas of the north outside of the NKPA’s retreat routes, few military forces remained to support Communist Party agendas. Boys and men who had been forced into NKPA service surrendered to the first UN soldiers they encountered and the remainder of the North’s army retreated toward China and the Soviet Union. As a result, some local Party leaders were left exposed for the first time to the direct wrath of the people who suffered under their rule.17

As the Allied forces surged north, some military leaders were surprised to discover that anti-Communist North Koreans had already taken matters into their own hands and liberated their districts. Pockets of disaffected North Koreans formed paramilitary units and chased Kim Il Sung’s police and military forces away. These anti-Communist partisans welcomed the UN troops and even helped them locate, attack, and harass retreating NKPA elements.18 Guerrillas like Kim Chang Song recalled that he contemplated “about what we should do to meet [the UN troops and join the] fight against Communism.”19 Making his move, “I had my people ambush each important [enemy] place.” They burned police stations to the ground with Molotov cocktails and destroyed several other military outposts.20 “We killed every Communist we found” and seized control of the district.21

By liberating themselves, the guerrillas inadvertently joined the Allied fight, but did so conditionally. Although the irregulars expressed contempt for Kim Il Sung’s Communists, they felt equal disdain for Syngman Rhee and his ROK government. Most wanted nothing more than to consolidate their newly regained freedom and enjoy some autonomy over their affairs without interference from both the North and South Korean governments. In areas like the mountainous Hwanghae region in the west, many of these rebels had fought long and hard to restore their control over their communities and lives.22

Unfortunately for the resistance members, the massive Chinese intervention in November 1950 ended their hopes for autonomy. Chinese formations quickly pushed the Allied troops out of North Korea. Faced with an untenable situation, tens of thousands of peasants chose to leave for the south; yet some decided to remain in the north and fight as guerrillas. In the more remote regions like Hwanghae and Pyongan, these anti-Communist fighters still controlled sizeable areas behind the lines of battle. In other locales, “semi-organized and partly armed” civilians fled to the numerous western islands off North Korea to continue their fight.23

The Allied naval blockade, its air superiority, and a lack of enemy landing craft made the islands safe for guerrillas and refugees alike. According to a contemporary study, “an exodus [of guerrillas] began in December [1950], reached the proportions of a mass flight, and ended on January 1951 when the Communists managed to gain the upper hand and close the [land] exits.” Left with few options, more than 10,000 lightly-armed irregulars and their families continued the fight from the islands. Refugees not interested in fighting hoped that the UN would return to free their villages and enable them to go home.24

In the winter of 1950/51, UN forces blunted the combined Communist Chinese and North Korean offensive. Allied planners began considering options to reunify the peninsula and factored the potential combat power of the partisan North Koreans behind the enemy lines into their plans. As one contemporary study noted, “a number of remote little islands in the Yellow Sea, unnoticed before … suddenly had become last-stand strongholds of North Korean antagonists to the Communist regime.”25 One EUSA officer concluded: “These volunteers have organized themselves, appointed leaders and, by virtue of their own initiative, have overcome numerous hardships while effectively combating [the enemy] and securing intelligence.” He also asserted that “These groups possess the will to resist, and if supplied, organized, and properly employed, would form the nucleus of an ever-growing liability to the Communist Forces.”26 How to get them committed to the UN effort remained to be seen.

That recaps the partisan situation at the end of 1950. Soon, EUSA received reports that large numbers of armed North Korean civilians occupied many of the offshore islands to the north and west. The same sources said they were engaging Communist forces and wanted UN support. The ROK Army and Navy did not trust the North Koreans and asked the U.S. Army to take charge of the situation. The EUSA G3 accepted the mission to train and direct the guerrilla war effort. “The problem was how to convert these untrained and [largely] unarmed volunteers into an effective fighting force and adapt their capabilities to missions advantageous to the over-all operations against the enemy.”27

EUSA had to create a guerrilla command to logistically support the partisan units, to provide basic infantry training, to support their operations with air and naval power, and to integrate their activities with the UNC. Fortunately, Colonel (COL) John H. McGee was an experienced guerrilla and special operations leader. He was capable of organizing and leading such a command. How COL McGee accomplished this mission is addressed in the following article.