NOTE

Although several authors have tried to recount the details of Operation SPITFIRE, to date none have managed to get the story straight. Because the failed airborne operation caused changes to how the guerrillas conducted similar actions afterward, it is important to fully understand the many factors that led to the debacle. This article presents a factual account of what was planned to happen, and what actually occurred during the execution of that plan. It is a synthesis of all of the facts as reported in all available primary source documentation.1

DOWNLOAD

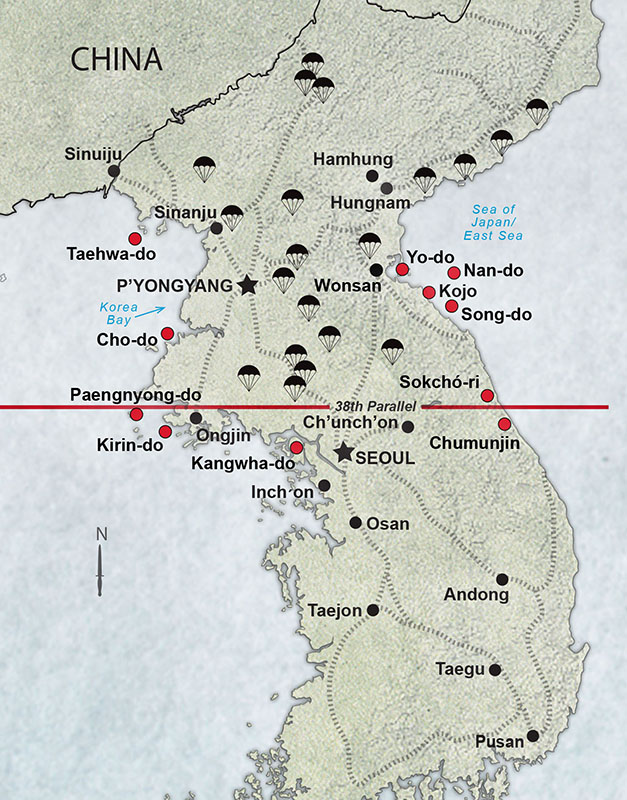

At 2200 hours on 18 June 1951, a five-man pathfinder element consisting of British Army Captain (CPT) William Ellery Anderson, Ranger Sergeant (SGT) William T. Miles, Jr., SGT Charles B. Garrett (communicator), and two Koreans (Song Chang Ok and Ho Yong Chong) parachuted from a C-47 ‘Skytrain’ into the mountains of North Korea. Problems surfaced immediately as two men (Anderson and Song) were injured in the jump and needed medical evacuation. Despite this rough start, the lead element discovered a large Chinese unit moving toward the UN lines and called in air support that inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy. The second element (CPT David C. Hearn, British Second Lieutenant (2LT) Leo S. Adams-Acton, British Fusilier Calder ‘George’ Mills and ten Koreans) parachuted in around 0130 hours on 26 June. Hearn had been added to replace the injured Anderson as the mission commander, and the latter was evacuated by helicopter on the 28th. Meanwhile, several more men were injured in the second jump and communications problems plagued the team.2

The earlier strike on the Chinese unit and the multiple attempts to resupply, reinforce, and evacuate SPITFIRE personnel had compromised the group’s location and enemy forces closed in to destroy it. Dawn airdrops by circling U.S. Air Force aircraft on the 6th of July led the enemy right to them. SGT Miles and Ho disappeared in a rear-guard action as the main body broke contact from the enemy; their bodies were never recovered. British Fusilier Mills and several Korean guerrillas met the same fate in the following days. The remainder, moving south and evading capture for almost three weeks, eventually bumped into the UN lines and linked up on 25 July with security elements of Item Company, 35th Infantry Regiment. Of the eighteen participants in the mission, only nine walked out or were recovered in the early medevac. SGT Miles, Fusilier Mills, and seven Koreans were never heard from again.3

After the guerrilla command’s disappointing second attempt to insert forces by parachute (VIRGINIA I on 15 March 1951 was the first), the Far East Command (FEC) prohibited non-Koreans from participating in future airborne special operations. This decision had far-reaching consequences, particularly for the hundreds of anti-Communist guerrillas who were later dispatched over North Korea in similar efforts.4 One fundamental problem with the decision was that it made no distinction between missions specifically designed to be long-term (i.e., deep insertions to establish ‘permanent’ guerrilla base camps) and shorter duration raids where deliberate withdrawals were an essential element of the planning. In issuing a blanket prohibition, the FEC staff exposed its ignorance of special operations in general and excluded experts (like the airborne-qualified Ranger infantrymen) from participating in airborne raids that they were well-qualified to accomplish.

Furthermore, the decision meant that all future participants of these operations would be newly trained individuals. Unlike American Rangers or other special operators, the guerrilla units possessed no ready pool of experienced airborne raiders. And until one survived a mission there could be no pool of experience to be sent on a second. Consequently, succeeding waves of poorly qualified, inexperienced Korean guerrillas were committed to one-way operations where none survived. Furthermore, with no feedback from survivors to determine what did or did not work, these operations constituted a ‘lessons-learned nightmare’ that saw one failed mission follow another. A vicious cycle began wherein at least seventeen similar operations were launched and “Not one member … is known to have exfiltrated.”5

The situation brings up a disturbing point: if Americans had participated in those later operations it seems doubtful that FEC would have continued to parachute units to their deaths like it did with the all-Korean groups. Some corrective actions would have been taken to increase the chances of recovering their personnel. Evidently, the FEC considered indigenous troops expendable and believed that by removing Americans/British from participation in missions such as these, there would no longer be a need to plan for extracts in event of emergencies.6 As a result, more than 400 Korean guerrillas were parachuted into North Korea between 22 January 1952 and 19 May 1953 and none were ever seen again.7