“Don’t go jumping into taking on the Japanese Army by yourselves, because if you are wiped out you are no good to anyone.”1– MAJ Jay D. Vanderpool

DOWNLOAD

One of the most important leaders in the U.S. Army’s guerrilla warfare campaign during the Korean War was Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Jay D. Vanderpool. Fortunately for the Korean guerrillas and the U.S. Army, LTC Vanderpool ‘cut his teeth’ on guerrilla operations while serving as an advisor to several Philippine groups fighting Japanese occupation forces during WWII. Although every guerrilla warfare situation is different, the experiences gained by Vanderpool in the field while being relentlessly pursued by the enemy gave him valuable insight into the unique problems faced by insurgents fighting to free their land from oppressors. He fully understood the complexities of guerrilla warfare and put knowledge gained in the Philippines to good use in Korea.

Born in Wetumka, Oklahoma, in 1917, Jay D. Vanderpool attended high school during the Depression and enlisted in the Army in 1936. Reaching the rank of staff sergeant in the Field Artillery, Vanderpool attended Officer Candidate School and earned an Army Reserve commission as a second lieutenant (2LT) on 5 April 1941. Assigned to the 8th Field Artillery Battalion, 22nd Infantry Brigade at Schofield Barracks, Hawaii, 2LT Vanderpool survived the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and fought at Guadalcanal with the 11th Marine Regiment and the 25th Infantry Division (ID). From battalion S-2, he quickly worked his way up to Deputy Chief of Staff (DCS), Intelligence (G-2), 25th ID in the assault landing at Kolombangara during the Solomons campaign. When the division moved to New Caledonia in early 1944 to prepare for the invasion of the Philippines, Major (MAJ) Vanderpool sought greater challenges.2

At that time, General (GEN) Douglas A. MacArthur’s headquarters in Australia became aware of the existence of several Philippine guerrilla organizations. To gain intelligence for the invasion of the Philippines, MacArthur’s G-2, Major General (MG) Charles A. Willoughby, created the Philippine Regional Section (PRS) to impose control and direction over the nebulous guerrilla network. Established on 15 May 1943, the PRS was directed by COL Courtney Whitney, a former Manila lawyer and “MacArthur’s trusted personal advisor.”3 As the planned invasion became imminent in late 1944, Whitney recruited and trained hundreds of individuals to serve as advisors to the many guerrilla units scattered throughout the 7,000 island archipelago. By October 1944, the PRS had inserted over 400 ‘agents’ (both U.S. and Filipino) into the islands. They fed vital information back to Willoughby’s analysts concerning enemy dispositions.4

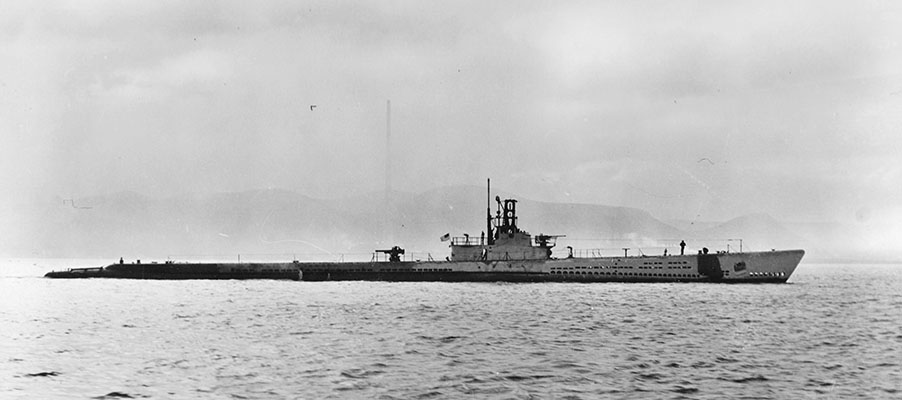

For his part, MAJ Vanderpool volunteered in September 1944 for a “highly hazardous program” and was selected for the PRS.5 After an intensive training course covering the establishment of intelligence networks and long-range communication systems, Vanderpool became one of sixteen “especially trained and equipped parties” dispatched to select resistance groups in the Philippines.6 With the vague guidance to “do what you think will best further the Allied cause,” Vanderpool boarded the attack submarine USS Cero (SS-225) bound for Luzon. After two aborted linkup attempts, the Cero reached the mouth of the Masanga River in East Luzon the night of 2 November 1944 and Vanderpool rowed ashore to a remote jungle beach. There, he linked up with his initial contact, Army Air Corps LTC Bernard L. Anderson, leader of a local guerrilla unit. Afterwards, he spent several days moving from house to house and church to church, until he finally arrived at the guerrilla encampment to begin his mission.7

MAJ Vanderpool served as MacArthur’s link with the several guerrilla units that operated in the Southern Luzon Sector, an area south of Manila spanning the Laguna-Cavite-Batangas area. His principal concern was ‘Hunter’s (ROTC) Guerrillas,’ led by former Philippine Army Cadet Eleuterio L. ‘Terry’ Adevoso (alias Terry Magtangol) in the region south of Manila. Characterized by Willoughby as the “most powerful guerrillas,” many of the Hunter’s group had been sergeants or officers in the Philippine Scouts and the rest, cadets in the Filipino military academy. Vanderpool assumed responsibility for several other small guerrilla units in the area, a region key to seizing the capital city of Manila.8

Vanderpool defined his role as ‘coordinator,’ advisor, and mentor to the guerrillas while supporting their operations in the field. He encouraged ‘his’ guerrillas to collect information on the enemy and personally relayed their reports to MacArthur’s headquarters. Vanderpool was the conduit for gaining the weapons, ammunition, and supplies that the guerrillas needed to function, and to gain recognition as patriots. More importantly, his fighters produced results. MAJ Vanderpool skillfully used his personality to exercise authority, persuading the guerrillas to put aside parochial differences and agendas to support American requirements.9

Vanderpool lived with the Filipino irregulars for five months, regularly moving among several disparate units to coordinate actions and avoid being captured by the Japanese. His influence expanded as he gradually took full charge. In late 1944 he formed his own General Guerrilla Command (GGC). The increased role of the GGC led Japanese intelligence officers to conclude that Vanderpool was a major general in command of multiple guerrilla units and they expended great time and energy to find him. Furthermore, Vanderpool’s fighters provided quality information, making them invaluable to MacArthur’s command after the U.S. landings on Luzon in January 1945.10

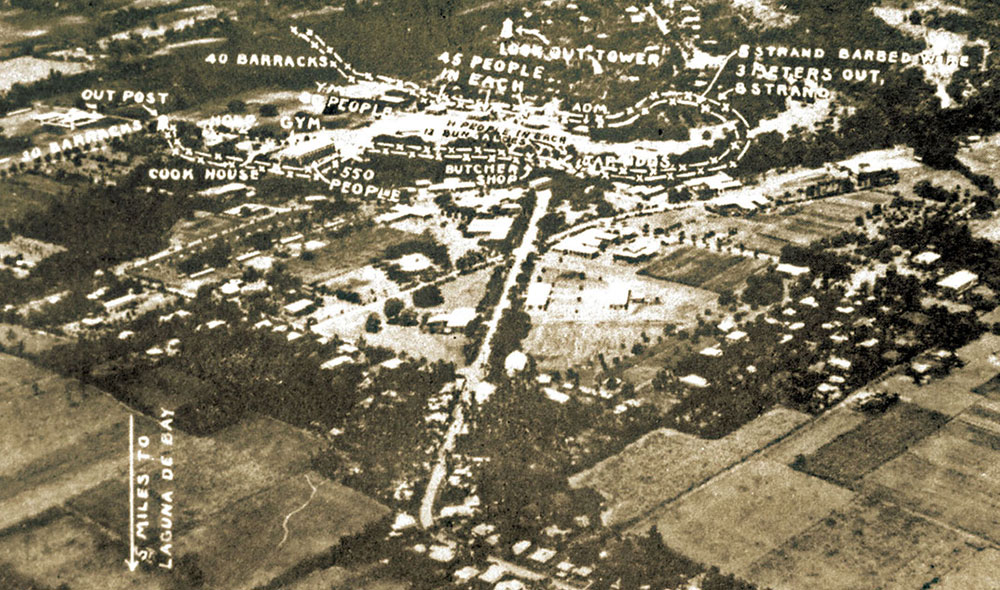

On several occasions Vanderpool’s guerrillas conducted significant combat operations. During the Los Baños raid (the rescue of 2,146 Allied prisoners in February 1945), Vanderpool assisted the 11th Airborne Division staff to plan the operation and directed his men to clandestinely pass instruction to the prisoners so they could get ready. Vanderpool’s guerrillas provided detailed information on the prison and served as ‘eyes on target’ for the attacking forces. Afterward, his men supported the division as they mopped up Japanese forces.11

On 15 April 1945, MAJ Vanderpool returned to his parent unit, the 25th ID. His knowledge of the Filipino culture, language, and geography proved extremely useful during fierce fighting at Balete Pass and Cagayan Valley in Northeastern Luzon. He remained with the division until February 1947, when he was seconded to the Central Intelligence Group, predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). In that capacity he became an expert on the North Korean military buildup. Vanderpool left the CIA and Korea in August of 1950 to attend the Artillery Officers Advanced Course before returning to Asia in June 1951 as an Intelligence Staff Officer in the FEC G-2 section in Tokyo, Japan.12

Vanderpool found the duties in the FEC G-2 to be “mostly paper work, rather dull.”13 He began looking around for something more challenging. “There was an opening to take charge of the partisan forces in Korea.”14 Acting quickly, “I negotiated a deal with the fellow who had the partisan job, who didn’t like it … , so arrangements were made for us to swap places. That’s the way I got to Korea” in December 1951, again leading guerrillas less than seven years after leaving his Filipino fighters.15 Vanderpool remained the commander of the EUSA guerrillas for sixteen months before departing Korea for good in April 1953. Throughout his tenure, he capably led the ‘partisans’ and American advisors and trainers, providing excellent guidance and leadership.16 COL Vanderpool was one of only a handful of American officers to command significant guerrilla groups in two major wars.