ABSTRACT

Shaped by the horrors of the 1980s Ugandan Bush War, young Joseph Kony declared himself a prophet and deliverer of the Acholi people. Instead, his Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) brutalized tens of thousands of African civilians. Heightened sensitivities to LRA atrocities led the U.S. to deploy Special Forces advisors in 2011. However, marksmanship and small unit training alone would not be enough to defeat Kony; more creative solutions were needed.

NOTE

All images and materials contained in Veritas are the property of the Department of Defense (DoD), unless otherwise noted.

TAKEAWAYS

- After the bloody Ugandan Bush War, Joseph Kony founded the LRA and used it to inflict extreme violence on innocent Ugandans

- The LRA became a regional threat by spreading violence into countries neighboring Uganda, increasing outside involvement

- ‘Kinetic’ military operations had proven unable to defeat Kony; NGOs demonstrated that creative solutions were needed to weaken the LRA

DOWNLOAD

In Operation OBSERVANT COMPASS, U.S. Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF) partnered with non-governmental organizations (NGOs), UN peacekeepers, and African military forces to end the violent threat of Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in central Africa. Key to mission success were U.S. Army psychological operations (PSYOP) efforts encouraging LRA members to defect. This campaign helped reduce the LRA from several hundred fighters when the operation started in October 2011, to less than one hundred when U.S. Africa Command (USAFRICOM) ended it in April 2017. An operational success, OBSERVANT COMPASS showcased the unique capabilities of the PSYOP Regiment.

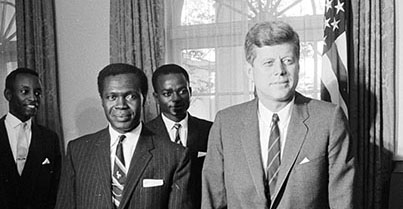

This preface explains the emergence of Kony and the LRA, providing historical context for the next article about the PSYOP role in OBSERVANT COMPASS. The roots of the LRA problem dated to post-colonial Uganda, following that nation’s independence from the United Kingdom in 1962. The new nation’s first head-of-state, Milton Obote, served as Prime Minister and President until 1971. He was overthrown by Ugandan Army General Idi Amin, which led to years of despotic rule, economic ruin, and human rights abuses.1

Idi Amin’s rule came at great cost to Uganda. During the 1970s, the self-proclaimed President for Life grew increasingly repressive against minorities and political opponents. Relations with the West soured as Amin warmed up to countries like the Soviet Union, East Germany, and Libya. As the Ugandan economy crumbled, he became expansionist, claiming parts of Kenya and invading Tanzania. In response, Tanzania, bolstered by the anti-Amin Ugandan National Liberation Front (UNLF)/Ugandan National Liberation Army (UNLA), invaded Uganda in 1979, forcing Amin to flee the country. After elections, Milton Obote returned as President, with the UNLA as the military arm of the government.2

Obote could not establish stability. He was deposed again in 1985 by another general, Tito Okello, but not before a bloody insurgency began against the UNLA. From 1981 to 1986, the Ugandan Bush War raged between the northern-based, Acholi-dominated government, and the southern-based, non-Acholi National Resistance Army (NRA), led by Yoweri Museveni.3 The death toll reached hundreds of thousands. Once the NRA defeated the UNLA, Museveni became President on 29 January 1986. Acholi-led rebel groups, namely the Holy Spirit Movement (HSM), opposed the NRA, but were defeated.4 From these conflicts emerged a 25-year-old Acholi named Joseph Kony.

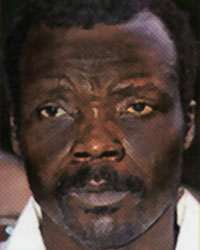

Kony’s past gave no hint of the monster he later became. Born in 1961 to Christian parents, Kony had a modest upbringing in the northern village of Odek. He abandoned school in the late 1970s to become a healer. After the Ugandan Bush War, Kony mourned the defeat of the HSM, led by his relative Alice Lakwena. Kony declared himself a prophet to the former rebels, and a deliverer of the Acholi people. In 1987, he formed the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) from the remnants of the HSM, to force a return to Uganda’s previous political structure, incorporating mysticism and Acholi nationalism into his message. Claiming access to spirits, Kony inspired his followers to view him as a messiah, while others feared his supposed power to curse them. The LRA leader used his occult influence to consolidate power and exact extreme violence on Ugandans.5

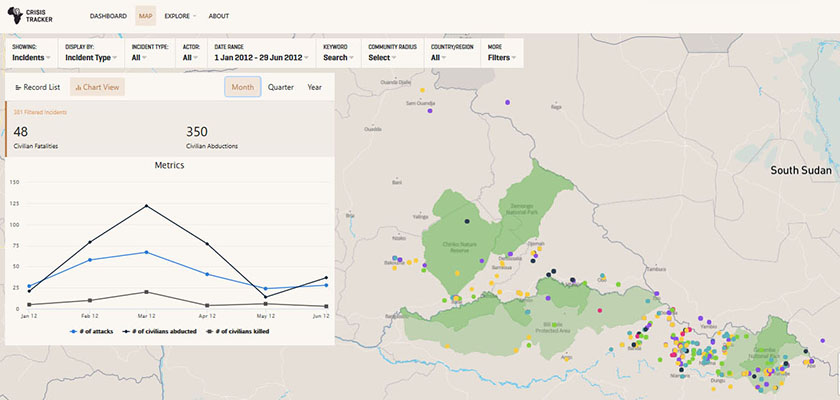

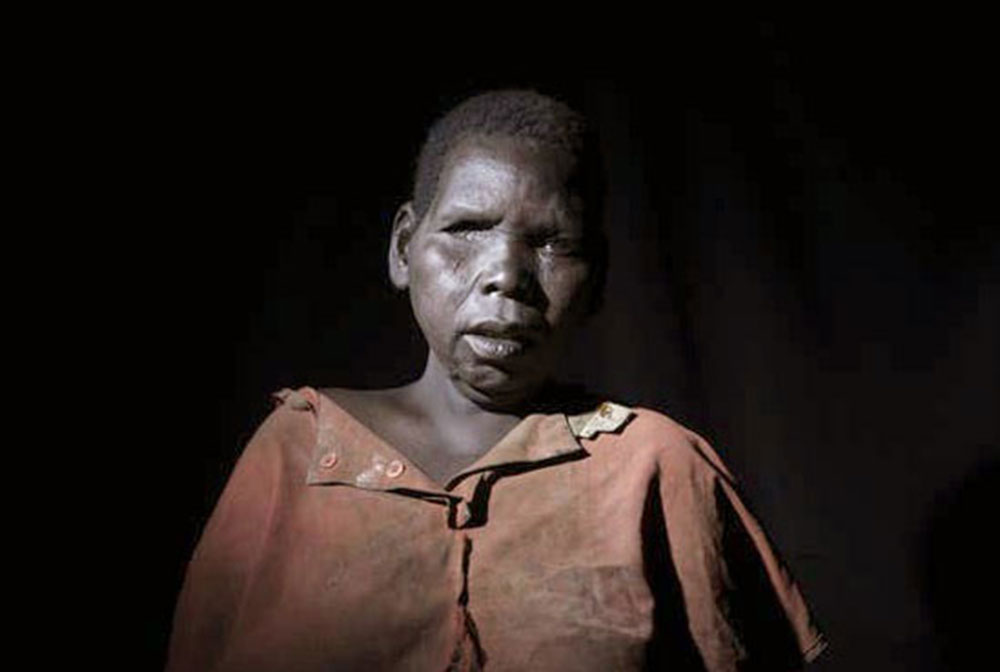

As one congressional research study argues, the LRA did “not have a clear … agenda, and its operations appear[ed] to be motivated by little more than the infliction of violence and the protection of senior leaders.”6 Kony ordered the LRA to attack and destroy villages, and torture, mutilate, and execute civilians. They abducted children to serve as porters, soldiers, and ‘bush-wives’.7 One NGO, The Enough Project, estimated LRA abductions at nearly 70,000 people (30,000 children) over thirty years.8 Among those brutalized were the Acholi, whom Kony distrusted since Museveni started recruiting them into the military after assuming power.9 In the 1990s, the Ugandan People’s Defense Force (UPDF) began attacking the LRA. This set a pattern of direct military engagement, followed by LRA soldiers scattering and causing violence elsewhere.10

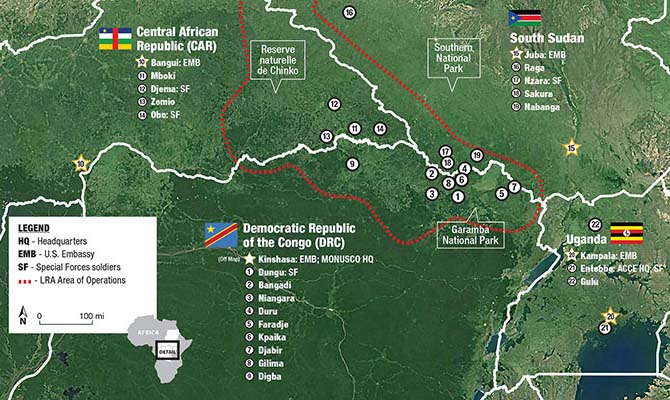

While the LRA was widely dismissed as a ‘Ugandan problem’, bordering nations were taking notice, and began guarding against it, among other regional threats. For example, in 1999, the UN Security Council created the UN Organization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUC) in response to the seemingly unrelated Second Congo War.11 This UN peacekeeping force, later re-designated MONUSCO, was headquartered in Kinshasa, capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. While the LRA was not MONUSCO’s first priority, peacekeepers located in the eastern part of that country formed a bulwark against the LRA in hopes of keeping them from coming in from Uganda.12

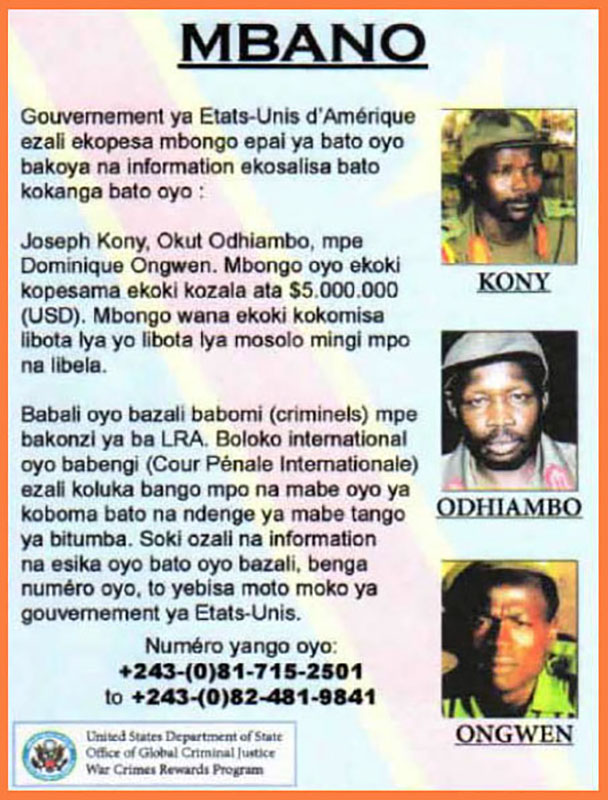

Continued LRA atrocities led the Ugandan government in 2005 to press the International Criminal Court in The Hague, Netherlands, to issue arrest warrants for Kony, Major General Okot Odhiambo, and Brigadier General Dominic Ongwen, for crimes against humanity. This raised the stakes for their capture, but failed to yield quick results.13 A glimmer of hope arose in 2006 when the UPDF pushed the LRA out of Uganda, and ceasefire talks began in Juba, the future capital of South Sudan. However, these negotiations foundered after two years. The LRA dispersed into Democratic Republic of the Congo and Central African Republic, and resumed atrocities. 14 With the LRA operating in four states and a roughly 164,000 square-mile area (about the size of California), it had become a regional problem.15

Heightened global awareness of the LRA led to U.S. involvement. In 2008, the State and Treasury Departments designated Kony a terrorist, and the U.S. began logistical support to UPDF-led counter-LRA operations, called LIGHTNING THUNDER.16 Meanwhile, U.S.-based NGOs lobbied to raise policy-makers’ interest in the LRA. Chief among these was Invisible Children, founded in 2004 “to end Africa’s longest running conflict led by Joseph Kony and [the LRA].”17 Their activism soon paid off.

In 2009, the U.S. Congress passed the “Lord’s Resistance Army Disarmament and Northern Uganda Recovery Act,” with 201 co-sponsors in the House of Representatives, and 64 in the Senate.18 President Barack H. Obama, who viewed Uganda as a key partner against terrorism in the region, signed it into law on 24 May 2010 (Public Law 111-172).19 The act committed to “increased, comprehensive U.S. efforts to help mitigate and eliminate the threat posed by the LRA to civilians and regional stability.”20 Its chief aim was “an end to the brutality and destruction that have been a hallmark of the LRA across several countries for two decades.”21 While the act did not directly authorize military action, it had another outcome.

Six months after signing the law, Obama presented his follow-on “Strategy to Support the Disarmament of the Lord’s Resistance Army” to the U.S. Congress.22 This “Strategy” consisted of four pillars:

- Protect civilians.

- Remove Joseph Kony and senior LRA commanders from the battlefield.

- Promote defection, disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration of LRA fighters.

- Support and provide humanitarian assistance to affected areas.23

Though the “Strategy” did not authorize military action either, it provided the core objectives for future operations.

Obama took one final step before deploying soldiers to aid the fight against Kony. In August 2011, he declared atrocity prevention a “core national security interest and … moral responsibility” of the U.S.24 Naturally, this applied to the LRA. Between general anti-Kony sentiment, Public Law 111-172, the November 2010 “Strategy,” and the formal declaration against atrocities, Obama had ample justification for direct U.S. military involvement. On 14 October 2011, the President informed U.S. Congress that he authorized deployment of the first combat-equipped U.S. soldiers to central Africa, with additional soldiers slated to arrive the following month. Obama set the force cap at 100, since their role was advisory only.25

Named OBSERVANT COMPASS, the mission’s broad objectives were the same as the November 2010 “Strategy.” The lead headquarters was the USAFRICOM Counter-LRA Control Element (ACCE [pronounced āce]), in Entebbe, Uganda. Colonel (COL) Russell A. Crane, 19th Special Forces Group (SFG), commanded both the ACCE and the Special Operations Command and Control Element ̶ Horn of Africa (SOCCE-HOA), at Camp Lemonnier, Djibouti.26 The ACCE reported to Special Operations Command, Africa (SOCAFRICA), in Stuttgart, Germany, commanded by Rear Admiral (RADM) Brian L. Losey, a U.S. Navy SEAL.27 As explained in the next article, Losey soon applied a ‘whole of SOCAF’ approach against Kony.

Nesting the counter-LRA mission within broader theater priorities was USAFRICOM, also located in Stuttgart.28 The Commander, USAFRICOM, U.S. Army General (GEN) Carter F. Ham, argued that OBSERVANT COMPASS was “best done through support, advising, and assistance, rather than U.S. military personnel in the lead … conducting the operations to try to find Kony and capture him. We are an enabling force to facilitate and advance the capabilities of the African forces.”29 Importantly, on 7 December 2011, the Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, Johnnie Carson, clarified that “this is not an open-ended commitment; we will regularly review and assess whether the advisory effect is sufficiently enhancing our objectives to justify continued deployment.”30