ABSTRACT

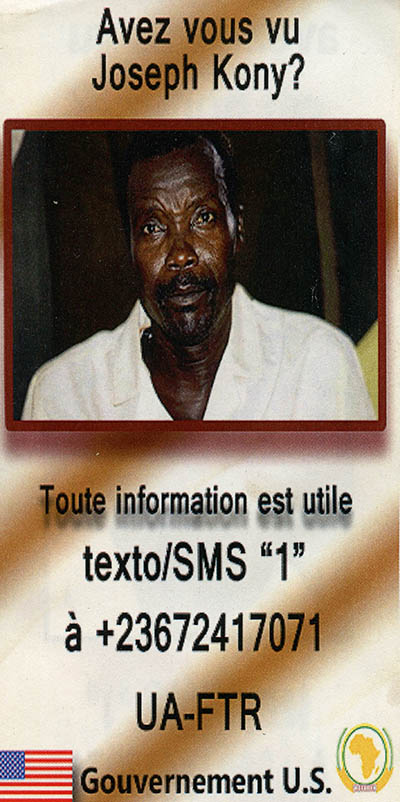

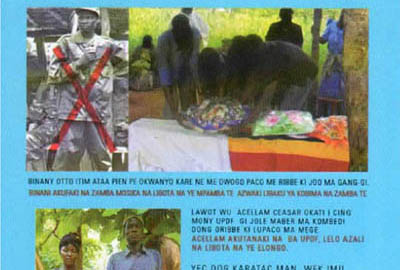

Sectarian and ethnic conflict, genocide, and slavery long plagued central Africa. Military actions by African armed forces had weakened but not defeated one regional threat, Joseph Kony and his Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). When the multi-national counter-LRA effort demanded creative solutions, Psychological Operations soldiers stepped in to help solve the problem.

TAKEAWAYS

- OBSERVANT COMPASS was an ‘economy of force’, requiring cooperation between multiple U.S. agencies, UN and partner forces, and NGOs

- Two 7th POB soldiers filled a critical gap, applying expertise and creativity ‘on the ground’ to bolster the multi-organizational LRA defection program

- The release and viral explosion of Kony 2012 on YouTube in March 2012 led to global visibility of U.S.-supported counter-LRA efforts in central Africa

NOTE

IAW USSOCOM sanitization protocol for historical articles on recent operations, pseudonyms are used for majors and below who are still on active duty, unless names have been publicly released for awards/decorations or DoD news release. Pseudonyms are identified with an asterisk (*). The eyes of active ARSOF personnel in photos are blocked out when not covered with dark visors or sunglasses, except when the photos were publicly released by a service or DoD. Source references (end notes) utilize the assigned pseudonym.

DOWNLOAD

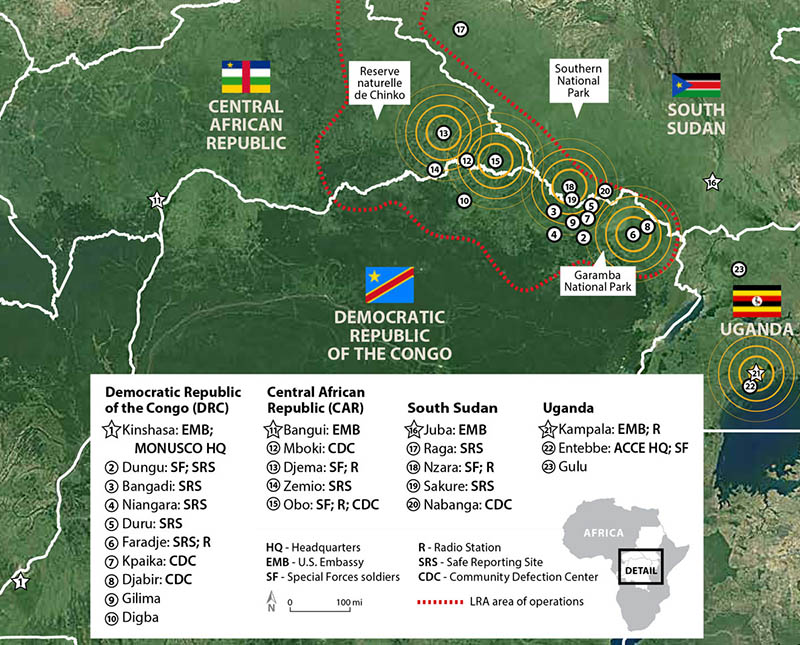

In fall 2011, Psychological Operations (PSYOP) Major (MAJ) Joseph A. Dewey reported to Kelley Barracks, in Stuttgart, Germany, as the PSYOP Planner in the J39 (Information Operations), Special Operations Command, Africa (SOCAFRICA). There, Dewey learned that U.S. President Barack H. Obama recently authorized the deployment of 100 combat-equipped soldiers to central Africa to support ongoing counter-Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) efforts.1 Named Operation OBSERVANT COMPASS, the mission involved 10th and 19th Special Forces Group (SFG) soldiers training counterparts from Uganda, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Central African Republic, South Sudan, and other multi-national forces. As the preface to this article explained, those partners sought to remove the brutal LRA from the battlefield.

Led by the mystic Acholi nationalist Joseph Kony, the LRA had perpetrated atrocities against civilians across central Africa since 1987. The President’s authorization finally committed the U.S. to aiding its allies against that threat. Even though encouraging LRA soldiers to defect was a core military objective, in practice the U.S. emphasized foreign internal defense (FID), an SF specialty, with no PSYOP personnel included at first. Thanks to a few enterprising PSYOP soldiers, that soon changed in a way that impacted the trajectory and outcome of OBSERVANT COMPASS. This article describes the deployment activities and accomplishments of the first PSYOP team in Uganda, from January to July 2012. The story begins in the J39, SOCAFRICA, with its newly arrived PSYOP Planner, MAJ Dewey.

Commissioned in 1996, the former Transportation and Chemical Officer had Bosnia and Kosovo deployments before switching to PSYOP in 2004. Deploying to Iraq as a detachment commander (Company C, 9th PSYOP Battalion [POB]), Dewey was then assigned to 6th POB. After leading Military Information Support Team (MIST) – Ethiopia, he became a Plans Officer on the 4th PSYOP Group staff. This led to a nine-month deployment supporting the Combined Forces Special Operations Component Command – Afghanistan. After serving as 5th POB Executive Officer, which included a tour with the Joint Information Support Task Force (Special Operations) (JISTF [SO]) in Qatar, he joined the J39, SOCAFRICA. From his new position in Germany, Dewey would play a key role in getting a PSYOP team into central Africa.2

OBSERVANT COMPASS rules of engagement dictated that U.S. soldiers could not directly attack the LRA. That restriction shaped the initial approach of the U.S. Africa Command (USAFRICOM) Counter-LRA Control Element (ACCE [pronounced āce]), the lead headquarters for the operation. Located in Entebbe, Uganda, the ACCE treated OBSERVANT COMPASS as a typical FID mission. However, the SOCAFRICA Commander, U.S. Navy SEAL Rear Admiral (RADM) Brian L. Losey, realized that ‘kinetic’ military operations had not yet defeated the LRA. Political interest in the crisis led Losey to adopt a “whole of SOCAFRICA” approach involving more than FID. He directed MAJ Dewey to “get after this problem.”3

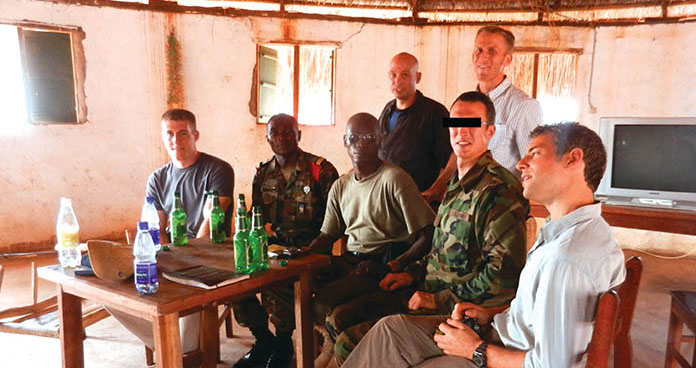

Despite his extensive experience, the PSYOP Planner saw this as a unique mission. He and Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Greg Mogavero, the new Information Operations (IO) Officer, discussed how to use Military Information Support Operations (MISO) against Kony.4 Lacking specific guidance or MISO authorities, they had a blank slate. Dewey spoke with 19th SFG leaders at the ACCE, and planned temporary duty (TDY) visits there. The first TDY was a one-week trip in January 2012, involving Dewey and his Non-Commissioned Officer-in-Charge (NCOIC), Master Sergeant (MSG) Geoff Ball, Jr.* Though confirming the ACCE’s FID-heavy approach, they also discovered that it was “receptive” to MISO.5

Given the OBSERVANT COMPASS objective of promoting LRA defections, PSYOP had an opportunity. However, the ‘maxed-out’ 100-person force cap required a workaround. MAJ Dewey contacted LTC Lee H. Evans, commander of the new, USAFRICOM-aligned 7th POB, at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.6 They planned to deploy two PSYOP soldiers to Camp Lemonnier, Djibouti, for assignment with the Regional Information Support Team (RIST), Special Operations Command and Control Element-Horn of Africa (SOCCE-HOA). The team would then go TDY to the ACCE, but could return to Djibouti quickly, if necessary.7 The mission would fall on two unsuspecting members from Company A, 7th POB: Captain (CPT) Adam R. Vance and Staff Sergeant (SSG) Nathan J. ‘Jed’ Todd.8

SSG Todd had reported to his Company A detachment in mid-2011, after studying Arabic at the Defense Language Institute (DLI) at Monterey, California.9Todd had enlisted in 1994, studied Russian at DLI, served in Military Intelligence (MI), and deployed to Bosnia with the 302nd MI Battalion from Germany. He left active duty in 1999, but later joined the 345th PSYOP Company, U.S. Army Reserve, in Lewisville, Texas. The PSYOP Specialist deployed to Afghanistan (2002) and Iraq (2004), before returning to active duty in 2006. Assigned to 9th POB, he supported 20th SFG during a second Iraq tour (2006-2007). As a 6th POB soldier, he deployed with MIST-Mali, partnering with the U.S. Embassy in Bamako on counter-terrorist messaging. With tactical and regional experience under his belt, SSG Todd joined 7th POB as a motivated, seasoned PSYOP NCO.10