FULL SERIES: SF IN BOLIVIA

- Beggar on a Throne of Gold: A Short History of Bolivia

- The 1960s: A Decade of Revolution

- The Sixties in America: Social Strife and International Conflict

- Che Guevarra: A False idol for Revolutionaries

- The ‘Haves and Have Nots’: U.S. & Bolivian Order of Battle

- “Today a New Stage Begins”: Che Guevara in Bolivia

- Turning the Tables on Che: The Training at La Esperanza

- Che’s Posse: Divided, Attrited, and Trapped

- The 2nd Ranger Battalion and the Capture of Che Guevara

- The Aftermath: Che, the Late 1960s, and the Bolovian Mission

DOWNLOAD

Although best associated with its counter-culture (flower-power) and music, the 1960s was a tremendously turbulent decade both domestically and internationally for the United States. As historian Dr. Terry H. Anderson stated, “The long decade was an endless pageant of political and cultural protests.”1 Other historians, Drs. George B. Tindall and David E. Shi said that “many social ills which had been festering for decades suddenly forced their way onto the national agenda.”2 Any U.S. soldier—serving overseas or stateside—would have been affected by the critical issues defining this period. This was particularly true of the Civil Rights Movement and the Cold War. This article will give a brief snapshot of the decade and show the reader the chaotic nature of 1960s America in relation to both themes. This will help explain why it was so important for the U.S. to stem Communist insurrections in its own “back yard”—like those inspired by the Cubans. The “Sixties” as they became known, started off as a continuation of the socially conservative and materialistic 1950s—itself an outgrowth of WWII—but quickly changed as many social and ethnic groups sought equality.

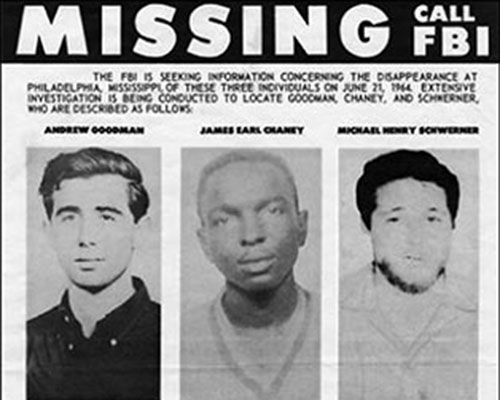

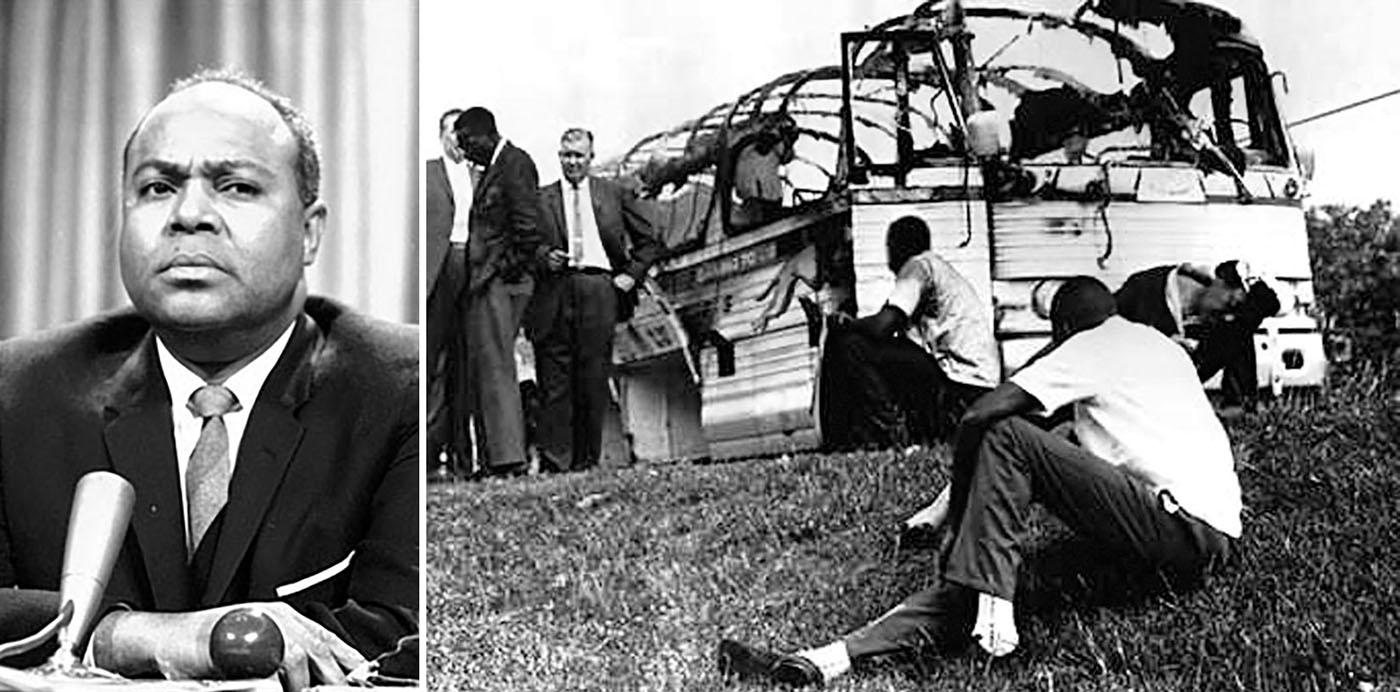

In the black community, the long-simmering Civil Rights Movement had gained momentum, even as it remained fragmented, multi-directional, and lacking a single leader. Although the forced integration of Little Rock Senior High School (Little Rock, Arkansas) in 1957 and sit-ins in Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1960 had gotten national attention, the “Freedom Rides,” which began in May 1961, raised awareness more. They were sponsored by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and led by James L. Farmer. The rides were designed to test whether the southern states would uphold federal laws to desegregate interstate travel facilities regardless of local mandates. Originally thirteen participants (seven black and six white) began the rides aboard commercial Trailways and Greyhound busses. They faced no significant opposition until reaching South Carolina. Then, hostility increased to outright violence—often while public law enforcement stood by and watched—as they traveled through the lower South.

Farmer described later events, “I was scared spitless and desperately wanted to avoid taking that ride to Jackson [Mississippi]. Alabama had chewed up the original thirteen interracial CORE Freedom Riders; they had been brutalized, hospitalized, and in one case disabled … blacks had been brutally pistol-whipped and clubbed with blackjacks and fists and then thrown, bloodied, into the back of the bus. Whites had been clobbered even worse for trying to intervene.”3 Television provided publicity and the momentum grew. Between June and September over 60 separate Freedom Rides took place as volunteers poured in despite the threats to life. The rides made the administration of President John F. Kennedy take notice as national attention was drawn to the Civil Rights Movement. At the same time, the violence embarrassed the United States internationally. However, the rides succeeded in forcing the desegregation of interstate travel facilities.4 Racial events continued into 1962 to keep Civil Rights on the front pages of national newspapers.

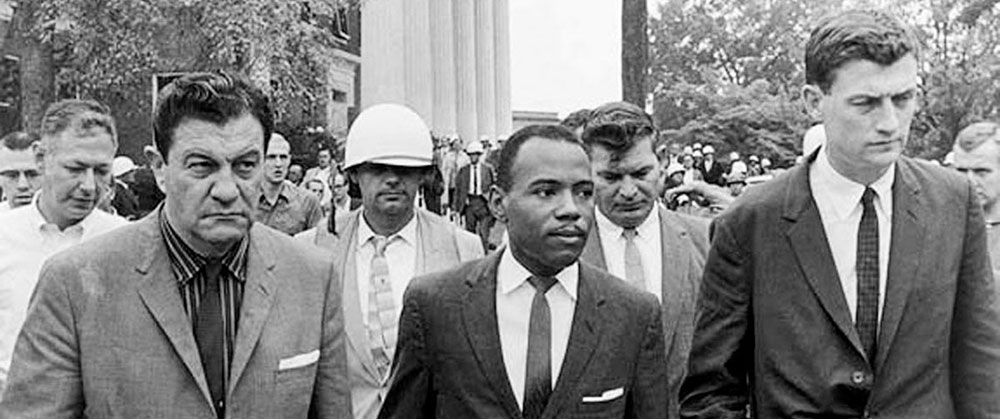

James Meredith, an African-American student, attempted to enroll at the University of Mississippi, known as “Ole Miss,” but had repeatedly been denied admission. The state government supported that position. After President Kennedy ordered U.S. Marshals and federal troops to Oxford, Mississippi, on 1 October 1962, Meredith was finally granted admission. Eventually 12,000 U.S. troops were required to keep and restore order at Ole Miss.5 But now Washington was acting on behalf of the movement.

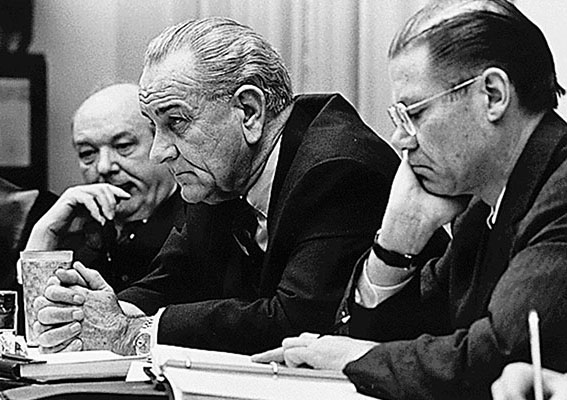

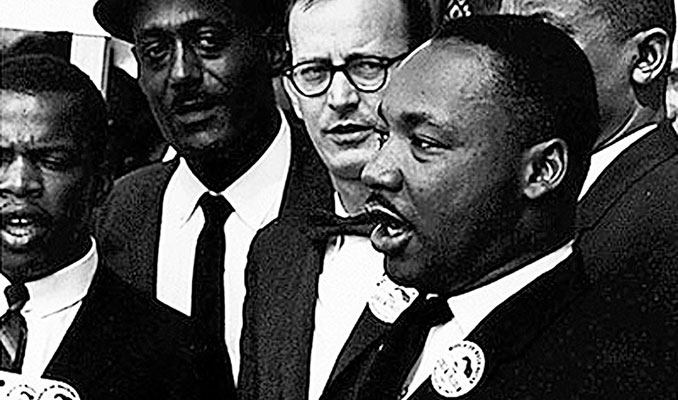

President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Memorial Day address on 30 May 1963 at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania [where President Abraham Lincoln had spoken a hundred years before] reinforced the federal government’s position: “Until justice is blind to color, until education is unaware of race, until opportunity is unconcerned with the color of men’s skins, emancipation will be a proclamation, not a fact.”6 On 28 August 1963 on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C., Civil Rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech during the “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.” The speech—considered one of the most influential in American history, ended with the words, “Let freedom ring. And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring - when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children - black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics - will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: ‘Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!”7 The speech electrified America, spurred the Movement forward, and helped to pave the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which outlawed segregation and discrimination in public places, schools, and places of employment. But King’s fervent speech was short-circuited by an event that shocked America.