FULL SERIES: SF IN BOLIVIA

- Beggar on a Throne of Gold: A Short History of Bolivia

- The 1960s: A Decade of Revolution

- The Sixties in America: Social Strife and International Conflict

- Che Guevarra: A False idol for Revolutionaries

- The ‘Haves and Have Nots’: U.S. & Bolivian Order of Battle

- “Today a New Stage Begins”: Che Guevara in Bolivia

- Turning the Tables on Che: The Training at La Esperanza

- Che’s Posse: Divided, Attrited, and Trapped

- The 2nd Ranger Battalion and the Capture of Che Guevara

- The Aftermath: Che, the Late 1960s, and the Bolovian Mission

DOWNLOAD

Bolivia is a land of sharp physical and social contrasts. Although blessed with enormous mineral wealth Bolivia was (and is) one of the poorest nations of Latin America and has been described as a “Beggar on a Throne of Gold.”1 This article presents a short description of Bolivia as it appeared in 1967 when Che Guevara prepared to export revolution to the center of South America. In Guevara’s estimation, Bolivia was ripe for revolution with its history of instability and a disenfranchised Indian population. This article covers the geography, history, and politics of Bolivia.

Geography and Demographics

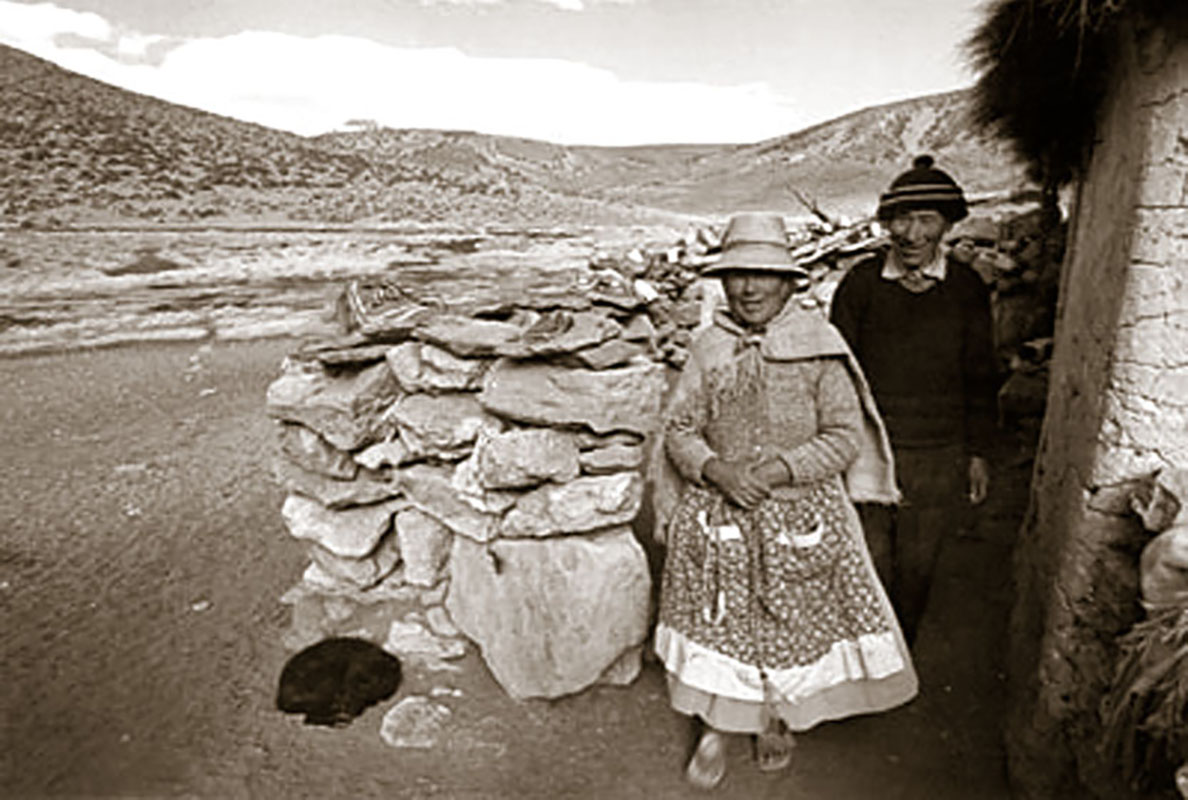

Bolivia’s terrain and people are extremely diverse. Since geography is a primary factor in the distribution of the population, these two aspects of Bolivia will be discussed together. In the 1960s Bolivian society was predominantly rural and Indian unlike the rest of South America. The Indians, primarily Quechua or Aymara, made up between fifty to seventy percent of the population. The three major Indian dialects are Quechua, Aymara, and Guaraní. The remainder of the population were whites and mixed races (called “mestizos”). It is difficult to get an accurate census because the Indians have always been transitory and there are cultural sensitivities. Race determines social status in Bolivian society. A mestizo may claim to be white to gain social status, just as an economically successful Indian may claim to be a mestizo or “cholo” (in Bolivian slang).2 Geography and demographics are intertwined.

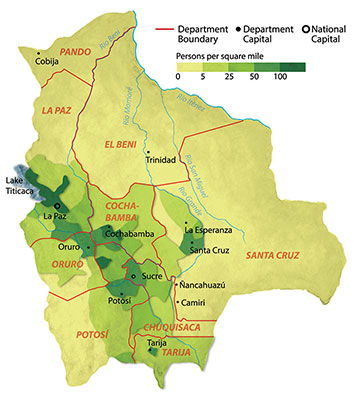

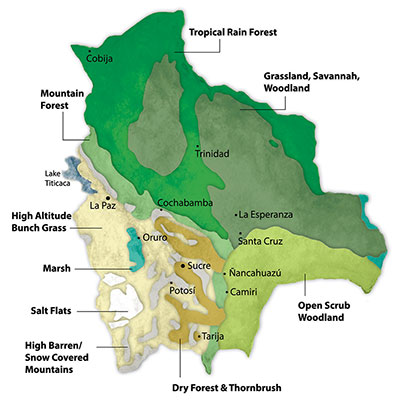

Geographers and geologists generally divide Bolivia into three geographic regions. The first region is the Andes Mountains and Altiplano, in the west and south. The Andes are actually two north-south parallel ranges (cordilleras). The western range (Cordillera Occidental) runs along the Peru and Chile borders. The eastern range (Cordillera Oriental) stretches from Peru to Argentina and Chile. In between the two ranges is the Altiplano, a highland desert plateau that is 500 miles long by 80 miles wide. The Altiplano is 12,000 to 13,000 feet above sea level.3 It gets very little rainfall because the two high cordilleras block rain clouds. Because of this, the scrub vegetation grows sparser towards the south, where the terrain is rocky with dry red clay. Northwest of La Paz on the Peru border is Lake Titicaca, the highest commercially navigable lake in the world. The major cities on the Altiplano are the capital, La Paz, and Potosí, both 13,000 feet above sea level. About three-fourths of Bolivia’s population lives on the Altiplano.4 The Quechua and Aymara have lived there for centuries.5 The Altiplano Indians speak either Quechua or Aymara and have little knowledge of Spanish (especially written).

The semitropical and temperate valleys of the northeastern mountain range (called the Cordillera Real) form the second Bolivian geographic region. These long narrow valleys called “Yungas” (the Aymara word for “warm valleys”) are cut by rivers, which drain to the east. Climate and rainfall make the Yungas some of the most fertile land in Bolivia, and they are filled with lush vegetation. The barely accessible high mountain slopes and peaks are largely uncultivated because road access is limited. Sucre and Cochabamba are located in this region.6 The rural population is predominately Indian. The whites and mestizos dominate the cities.

The third region, the Oriente, is composed of the eastern tropical lowland plains (called llanos) that cover about two-thirds of the country.7 The Oriente is further subdivided into three areas based on topography and climate. The northern Oriente, primarily the Beni and Pando Departments and the northern part of Cochabamba Department, is tropical rain forest. During the rainy season, from October to May, transportation is difficult because large parts turn into swamp. By the 1960s, travel was increasingly done with aircraft or boats because of this. The entire Beni region (Amazon basin) is sparsely populated by approximately thirty different Indian groups.8

Moving south is the transitional zone with a drier climate, which comprises the northern half of the Santa Cruz Department. Here belts of tropical rainforests alternate with savanna grass plains. Large sections of land were cleared for farming and cattle ranching. In the late 1920s oil and natural gas exploration took place in this region. The largest city is Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz de la Sierra), which in the 1960s had considerable economic growth.9 While mestizos migrated to the area looking for opportunity, two very insular communities are east of Santa Cruz. In the 1950s several thousand Japanese and Okinawans emigrated to farm fruit, rice, and vegetables. There are also several large Mennonite communities east of Santa Cruz.10

The final region is the southeastern most part of the Oriente lowlands called “the Chaco” (sometimes called the Gran Chaco or the Chaco Desert). The Chaco is basically a huge flat expanse, which has a striking climate contrast.It becomes increasingly drier moving from east to west. After a dry season of nine months (April to December), the desert transforms into a vast insect-infested swamp during a three-month long rainy season. These extremes in climate and rainfall support thorny brush jungle and grassy areas for cattle.11 Cheap land brought few settlers to this inhospitable region.12 However, it did attract Che Guevara in 1967.

It was the hostile area bordering the Chaco that Che selected for his guerrilla foco base. The countryside has rolling hills with deep, densely wooded, thorn infested ravines (canyons or gullies) that generally run north - south. In the center of the area, the Ñancahuazú River twists its way through a steep canyon where smaller streams and gullies branch off the main river. Narrow riverbanks sporadically disappear into the canyon walls. The canyon sides are covered with thickets of reeds, trees, vines, and cacti. Hilltops are largely barren with small trees and scrub vegetation. Paths are limited, and cutting a trail with a machete is often necessary.13

The area around the Ñancahuazú River is sparsely populated with small towns and villages. There are few roads. The population is a mix of people, primarily lowland Guaraní Indians and poor mestizos who migrated for cheap land. This area had been part of a government land reform program giving ten-hectare homesteads (about 25 acres) to about 16,000 families.14 People cluster in small, isolated communities to eke out a living by farming, cattle ranching, or working on government oil and public works projects. The major transportation artery is the Santa Cruz - Cochabamba highway that connects the area to the Altiplano.

History

The history of Bolivia in the 1960s reflects its pre-Columbian and Spanish colonial heritage. The Indian groups eventually formed two “great” kingdoms, the Aymara and the Inca (Quechua).15 The Spanish conquest led by Francisco Pizarro began in 1526. During 300 years of colonial rule, Spain imposed its political and social institutions on a predominantly extractive economy that concentrated on mineral exports – first silver, and then tin – using Indian forced labor. After a hard struggle to gain independence in 1825, Bolivia’s history was marked with political and territorial insecurity. The one constant during the 18th and 19th centuries in Bolivia was instability.

Pre-Columbian History

The Inca Empire began expanding from the highlands of Peru in the early 13th century. In 1438, the Incas incorporated a large portion of western South America that included the Bolivian Altiplano. The empire was created and expanded by peaceful integration and military conquest. At its height the Incas controlled about 12 million people. The Inca Empire included large parts of today’s Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Argentina, Chile, and Colombia.

The Conquest

Francisco Pizarro, with fewer than 200 men, toppled the Inca Empire. Pizarro took advantage of the instability caused by a recent civil war, a smallpox epidemic, and European military technology to seize power. The death of Huayna Capac caused fighting between two half brothers, Huáscar and Atahualpa, over the succession to the Inca throne.16 After a three-year-long civil war (1529-1532) Atahualpa defeated Huáscar, just as the Spaniards arrived.17 On 16 November 1532, Pizarro captured Atahualpa and demanded a ransom for his life. After a large room was filled with gold and silver, the Inca ruler was executed.18 The conquistadors spent ten years consolidating power in the Andean region. Although there were several Indian rebellions, they were quickly put down. For 300 years Spain controlled what is present day Bolivia.

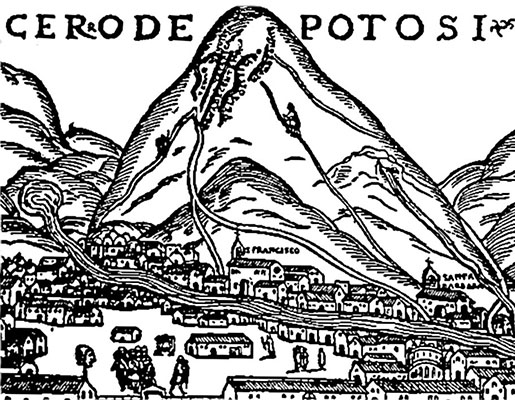

Colonialism – Upper Peru

The new colony called “Upper Peru,” (Bolivia) had been a neglected part of the Inca Empire. This continued under Spanish colonial rule until 1545 when large silver deposits were found at Potosí nearly 13,800 feet above sea level.19 That discovery transformed the backwater into the wealthiest part of the Spanish empire. Although the Spanish crown received 20% of the silver extracted, it fueled the entire region’s economy. The remote location of Potosí meant that everything – food, tools, animals, and labor – to support mining had to be imported.20 In 1548 the town of La Paz was established on the trade route between the silver mines and the colonial capital at Lima, Peru. By 1650 Potosí was the largest city in South America (120,000 to 160,000 people when London had about 400,000).21 Silver extracted from Potosí became the principal source of Spanish royal wealth for three hundred years.

Independence

The Spanish empire began to weaken when the French occupied Spain during the Napoleonic Wars. As Spanish royal authority weakened, two independence movements sprang up in South America. In the north, forces under Simón Bolívar fought the royalist armies in Venezuela, Colombia, and Ecuador. From Argentina, José de San Martín and Bernardo O’Higgins led forces across the Andes to free Chile, and then fought north to free Peru. Independence in Upper Peru was proclaimed in 1809, but it took 16 years of struggle to establish the republic named for Simón Bolívar, the Great Liberator. Bolivia was established on 6 August 1825; however, independence did not bring stability.

Bolivia’s future was marred by political turmoil and military defeats. In 1867, Bolivia lost territory in the north to Brazil. During the War of the Pacific (1879-1883), Bolivia allied with Peru against Chile. The clash was prompted by economics, over an unlikely source of revenue, guano (the nitrate-rich excrement of seabirds, bats, and seals).25 Chile prevailed on land and sea and occupied the Peruvian capital, Lima.26 Bolivia lost areas rich in natural resources, as well as its national pride. Most significantly, Bolivia lost access to the Pacific Ocean, making it a landlocked country.27

Interim

From 1884 until the 1930s Bolivia enjoyed relative stability. The economy took a jump as tin replaced silver as the major export. World demand fostered the expansion of railways to transport the tin to the United States and Europe.28 Bolivian intellectuals blamed Chile for its defeat in the War of the Pacific. Using reverse psychology, they promoted the need to create a national identity to overcome centuries of backwardness. Rival political parties worked for political and economic modernization. The politicians in government, elected by a small, literate, and Spanish-speaking electorate reorganized, reequipped, and professionalized the disgraced armed forces. They provided stability and prosperity into the next century.

The 20th century was marked with three great events: the Chaco War, World War II, and the 1952 Revolution. The Chaco War was the last territorial loss for the country, but, more importantly it politicized a generation, both politically and militarily, to seek change. World War II and the need for tin kept the economy moving forward. The 1952 Bolivian Revolution caused drastic political, social, and economic changes. Most important, universal suffrage promised the majority Indian population more voice in government and massive land reform was decreed to improve life for the poor.

The Chaco War

The Chaco War with Paraguay was fought to regain the Chaco and gain access to the sea via the navigable Paraguay River. Both were needed for economic growth and for oil exploration. Control of the Paraguay River and the Chaco region also affected the production of yerba maté, Paraguay’s major export.29 A series of escalating border incidents were the impetus for war. Convinced that Bolivia’s larger army could win, President Daniel Salamanca broke diplomatic relations and declared war on Paraguay in 1932.

On paper, the Bolivians had a huge advantage over the Paraguayans. Bolivia had more national resources, including population, and a larger Army, trained by German expatriates. However, the Army was filled with conscripted and ill-trained Indians from the Altiplano, most of whom had never been out of their villages. Relocation to the harsh climate of the Chaco resulted in enormous non-battle casualties from sickness, hunger, and dehydration. Led by former German General Hans Kundt, the army launched World War I style mass assaults that proved disastrous. A 1,000-mile long road was the sole supply line for the Bolivians, further hampering operations.30 Bolivian losses were staggering: 65,000 of the 250,000-man Army were killed, deserted, or perished in captivity.31 With a population of only 2 million, Bolivian per capita losses rivaled French and British losses in the First World War.32 Paraguay suffered as well. They lost 36,000 soldiers of 140,000 mobilized.33 After three years of fighting the Paraguayan army forced the Bolivians out of the Chaco.

The Chaco War was traumatic to Bolivia. The loss of territory and prestige was yet another blow to the national psyche. Bolivia lost 115,000 more square miles of territory, about a fifth of the country.34 It was the catalyst for political change. The veterans became the “Chaco Generation” and pushed for political and military reforms for the next three decades.35 The defeat in the Chaco set the stage for the 1952 Bolivian National Revolution.

The 1952 Bolivian National Revolution

The Chaco War was a turning point for Bolivia. Although legally a democracy, the predominately white electorate constituted only 5% of the population. Indian veterans returned to their villages without the right to vote and little, if any, political power. In 1941, Víctor Paz Estenssoro led the formation of the Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario (MNR), the Nationalist Revolutionary Movement. It grew in strength during World War II and afterward by aligning itself with the miners unions, the strongest in the country.38 In 1949 the MNR staged a popular uprising that was quickly crushed by the military. Víctor Paz Estenssoro and other party leaders fled into exile and devoted themselves to reorganizing for the next three years.39

On 9 April 1952, a new successful MNR revolt became the Bolivian National Revolution. This was not a bloodless coup d’état. Over 1,500 died bringing the MNR to power.40 Víctor Paz Estenssoro was quickly elected president. The MNR implemented wide-ranging reforms, including universal adult suffrage, massive land reform, rural education, and nationalization of the tin mines. The national government for the first time in the country’s history worked to integrate the Indians (the majority of the population) into the national social structure. To prevent a military coup d’etat, the Bolivian Army was abolished and the military academy closed. Both were reinstated within the first six months of the MNR administration, but with a new mission, to promote civic action throughout the country.41

The MNR stayed in power for an unprecedented twelve years.42 Paz Estenssoro’s vice-president, Hernán Siles Zuazo, succeeded him in 1956. Paz Estenssoro was re-elected for a second time in 1960 and changed the constitution to enable himself to run again in 1964. After he won the 1964 election with 70% of the vote, the military staged a coup d’état.43

The 1964 Coup

On 4 November 1964, the Vice President, General René Barrientos, and the Army Commander, General Alfredo Ovando Candía, overthrew the MNR government. The new junta called its action a “restorative revolution” to stop MNR excesses and eliminate corruption.44 Barrientos and Ovando ruled jointly in a military junta for two years until 2 January 1966, when Barrientos resigned and ran for president. He won the election with 54% of the popular vote and took office on 6 August 1966.45 General Ovando continued as the Army Commander.46

Conclusion

In 1967, Bolivia appeared ready for change. The 1964 coup put the military back in power, but after the 1966 election, the Army returned to its barracks. Three major events shaped the country: the War of the Pacific during which Bolivia lost a mineral rich area, making it a landlocked country; the Chaco War resulted in more territorial losses, but more importantly, severely reduced its manpower for twenty years; and the 1952 Revolution redefined the political, social, and economic landscape. In Che Guevara’s estimation, Bolivia, with its history of instability and a disenfranchised Indian population, was the perfect breeding ground for revolution. Bolivia became his test case for launching revolution throughout South America.