FULL SERIES: SF IN BOLIVIA

- Beggar on a Throne of Gold: A Short History of Bolivia

- The 1960s: A Decade of Revolution

- The Sixties in America: Social Strife and International Conflict

- Che Guevarra: A False idol for Revolutionaries

- The ‘Haves and Have Nots’: U.S. & Bolivian Order of Battle

- “Today a New Stage Begins”: Che Guevara in Bolivia

- Turning the Tables on Che: The Training at La Esperanza

- Che’s Posse: Divided, Attrited, and Trapped

- The 2nd Ranger Battalion and the Capture of Che Guevara

- The Aftermath: Che, the Late 1960s, and the Bolovian Mission

DOWNLOAD

In the mid-1960s, Ernesto “Che” Guevara de la Serna, was a clear threat to American foreign policy in Latin America. His role in Cuba’s Revolution, his outspoken criticism of the United States, and his proponency for armed Communist insurgencies in the Western Hemisphere, made him one of Washington’s top intelligence and military targets. “This asthmatic … who never went to military school or owned a brass button had a greater influence on inter-American military policies than any single man since the end of Josef Stalin.”1 Che’s part in establishing the first Communist government in Latin America was legendary in the region. In essence, the U.S. Government was concerned by, not just Che the man, but what he proselytized on insurgency and instability. He was the Osama Bin Laden of the 1960s.

Che’s image has transcended reality to that of a romantic hero. But ask any Cuban exile in the United States today and they will say that Che was simply a ruthless Communist revolutionary.2 Best known for his brutality in Cuba, he was deeply involved in unsuccessful insurgencies in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Bolivia. While not a thorough account of his life, this article summarizes Che’s youth, idealism, and the revolutionary path that led him to Bolivia.

Ernesto was born on 14 May 1928 in Rosario, Argentina, to Ernesto Guevara Lynch and Celia de la Serna.3 The first of five children, he was raised in an upper middle class family. His father was related to one of South America’s most established families. While he squandered an inheritance, his wife, Celia, had her own and an estate that provided a small yearly income. Ernesto’s upbringing was bohemian; as a boy he was free to do as he wished. But he was born with a serious, lingering ailment.

From the age of two Ernesto suffered from severe asthma, forcing the family to live in a dry region. His father complained that “each day we found ourselves more at the mercy of that damned sickness.”4 The asthma made the often-bedridden Ernesto a voracious reader. He was also determined to lead an active life.

Ernesto played sports and engaged in daredevil antics to impress his friends. Although of slight build, he was especially good at rugby. His bohemian eccentricities earned him nicknames, the most unflattering being “Chancho” (pig), because Ernesto did not bathe regularly and wore unwashed clothes for weeks. Despite his nonconformity, Guevara chose to study medicine at the University of Buenos Aires and explore the country.

On his trips Guevara noticed the vast differences in living standards between the rural population and his social class. These forays into the countryside manifested a feeling of pan-Americanism, a desire to help the poor, and reinforced his hatred of the landed aristocracy in South America and the U.S. Despite being bourgeois, he held them responsible for Latin America’s oppressed indigenous population. The adventure that most influenced the 24-year-old Ernesto began in January 1952. Partnered with Alberto Granado, he traveled through Argentina, Chile, Peru, Ecuador, Panama, Venezuela, Colombia, and the United States.5 After nine months of travel and discovery, Ernesto was infused with a newfound sense of direction. He returned to Buenos Aires and completed his medical studies in April 1953.

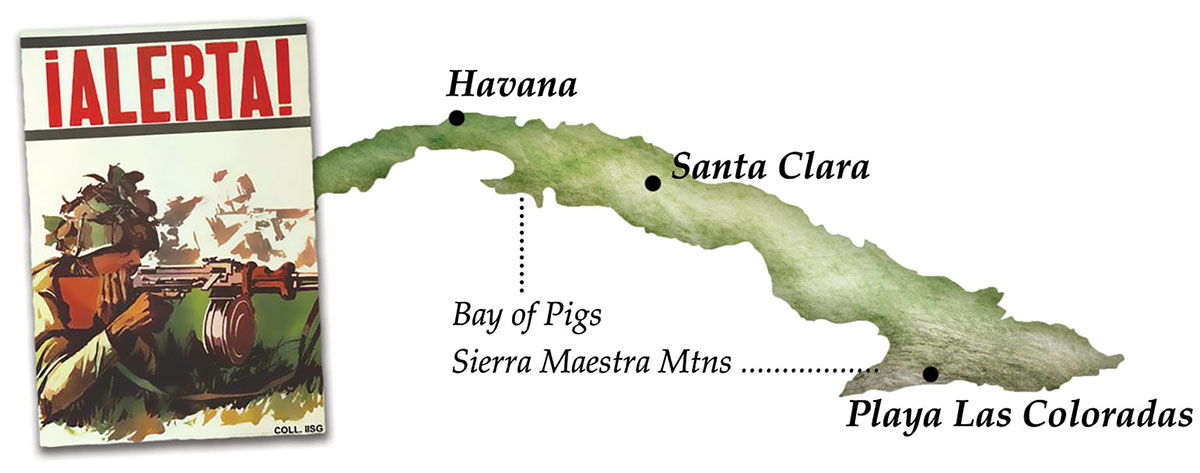

The newly minted doctor once again took to the open road. After observing firsthand the results of the 1952 Bolivian Revolution in La Paz, he left for Guatemala to support the socialist president, a former Army officer named Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán. There, Ernesto met his future wife, Hilda Gadea and got the nickname, “Che,” from Cuban political exile Antonio “Ñico” López who made fun of him for constantly using the Argentine expression che [hey!].6 The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) orchestrated overthrow of President Arbenz in 1954 had a profound effect on Che Guevara. Afterwards, he looked back on Guatemala as a revolution that could have succeeded if those in power had been more forceful.

Arbenz’s populism, especially land reform and cooperation with Socialists, attracted international attention. In 1954, two percent of Guatemala’s population owned 72 percent of the arable land. Since only 12 percent of that land was being used annually, Arbenz wanted to redistribute the rest. This did not please the powerful and influential U.S.-based United Fruit Company (UFC), which was Guatemala’s largest landowner. In the midst of a “Red Scare,” Washington responded to the UFC’s pleas for help, in part because America was not keen on a left-leaning government in the Western Hemisphere. Thus, the CIA trained a force in Nicaragua to overthrow Arbenz.

On 18 June 1954, nearly 500 men commanded by Carlos Castillo Armas crossed the border in four groups. Although the CIA-trained rebels were dealt severe blows, the revolt of the Guatemalan Army enabled final success. Arbenz was forced into exile. Those suspected of Socialist sympathies were arrested. Che took refuge inside the Argentine Embassy before fleeing to Mexico City.

Che’s revolutionary colleagues from Guatemala joined him there. Ñico López introduced him to Fidel Castro, whom Che thought was “intelligent, very sure of himself and of extraordinary audacity; I think there is a mutual sympathy between us.”7 When Castro invited him to join the 26th of July Movement, Che accepted.