FULL SERIES: SF IN BOLIVIA

- Beggar on a Throne of Gold: A Short History of Bolivia

- The 1960s: A Decade of Revolution

- The Sixties in America: Social Strife and International Conflict

- Che Guevarra: A False idol for Revolutionaries

- The ‘Haves and Have Nots’: U.S. & Bolivian Order of Battle

- “Today a New Stage Begins”: Che Guevara in Bolivia

- Turning the Tables on Che: The Training at La Esperanza

- Che’s Posse: Divided, Attrited, and Trapped

- The 2nd Ranger Battalion and the Capture of Che Guevara

- The Aftermath: Che, the Late 1960s, and the Bolovian Mission

DOWNLOAD

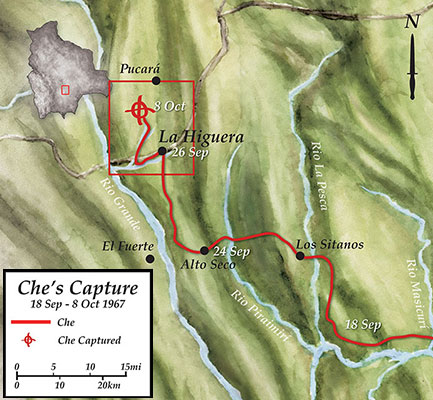

On 26 September 1967, the ragged band of 22 insurgents led by Ernesto “Che” Guevara, entered the small hilltop town of La Higuera above the Rio Grande in Bolivia’s Cochabamba Province. Finding the town deserted except for a handful of old women, Che discovered that the Bolivian authorities knew his presence in the area when he found a telegram to the village mayor warning of his approach. When the sick, dispirited guerrillas left the village, the Bolivian Army ambushed them, killing three men. The guerrillas fled two kilometers to the west, into the rugged, broken canyons leading down to the river.1 (Two Bolivian guerrillas deserted during the move into the canyons). This article will look at the final episode in Che’s Bolivian adventure when he is captured on 8 October by the 2nd Rangers.

Following the graduation ceremony on 19 September 1967, the Bolivian Army’s 2nd Ranger Battalion departed the 8th Infantry Division headquarters at Santa Cruz. The troops were loaded to capacity on stake bed sugar cane trucks. The battalion was headed for the Zona Rosa, the “Red Zone” along the Rio Grande near the town of Vallegrande. This was the reported area of operation of the band of guerrillas led by Che Guevara. The battalion’s mission was to destroy the insurgents.

The 650-man 2nd Ranger Battalion was Bolivian President René Barrientos Ortuño’s response to the guerrilla attacks in March 1967. Barrientos directed the creation of the unit and asked the United States for assistance in training. A 16-man Mobile Training Team (MTT) from the 8th Special Forces Group in the Canal Zone, Panama, under the command of Major (MAJ) Ralph W. Shelton arrived in April. Over the course of nineteen weeks, the team turned the untrained conscripts into “the best-trained unit in the Bolivian Army.”2 Within two weeks of their graduation, the Rangers lived up to that assessment.

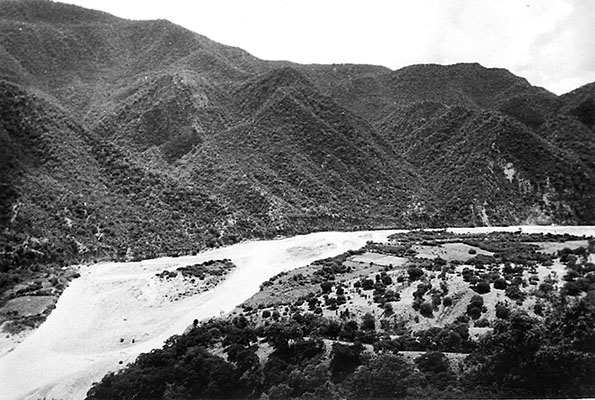

Since late June, Che and his now seventeen-man force were under constant pressure from the Bolivian Army. His original force had been divided and decimated in contacts with the Bolivian Army. Forced into constant movement, shortages of food, medicine and equipment had worn the guerrillas down and caused several desertions. Units from the Bolivian Army’s 4th and 8th Divisions cordoned off the area north and south of the Rio Grande and gradually surrounded the guerrillas. The terrain had rolling hills with deep, densely wooded, thorn infested ravines that generally ran north to south. Narrow riverbanks sporadically disappeared into the canyon walls. The canyon sides were covered with dense thickets of reeds, trees, vines, and cacti. Hilltops were largely barren except for small trees and scrub vegetation.3 In the rough, broken terrain of deep ravines and thick vegetation, the Army could not find the guerrillas. Che and his men continued to move, seeking a way to break out of the encirclement.

After the 2nd Ranger Battalion was trucked to Vallegrande on 26 September, Colonel Joaquín Zenteno Anaya, the 8th Division commander, sent Company B (Captain Gary Prado Salmón) in pursuit of the guerrillas that fled La Higuera.4 Prado’s men rode to the village of Pucará and marched through the night to take up positions at the southern entrance of San Antonio Canyon. By 30 September the insurgents were bottled up. Che and his forces were given a brief respite as Army troops conducted thorough sweeps along the Rio Grande, but did not venture into the narrow canyons.

Company B searched along the north and south banks of the Rio Grande until October 4th when they set up a patrol base near Abra del Pichaco at the mouth of San Antonio Canyon. Two sections (platoons) from A Company (Captain Celso Torrelio) were attached to Prado’s company and positioned near La Higuera. Prado now had 200 Rangers under his command. The remainder of Torrelio’s company was given the mission of combing the ravines to the east of San Antonio Canyon. The Ranger companies continued searching the area without success until 8 October. Then, a crucial piece of intelligence was received.

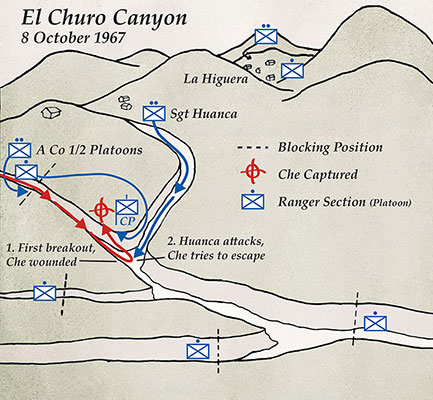

That morning (8 October) at 6:30 am, Second Lieutenant Carlos Perez, the First Section (Platoon) Leader in Company A (attached to B Company), reported that Pedro Peña, a local campesino, watched seventeen men skirt his potato field to enter El Churo Canyon the evening before.5 Perez contacted Prado on his AN/PRC-6 radio and was directed to move the two A Company sections to the north end of El Churo Canyon while Prado positioned himself with one rifle section, two 60 mm mortars and one Browning M1919A6 .30 cal machine gun on the high ground overlooking the south end of the small ravine. The Ranger company immediately began to close off the ends of the canyon. The net around Che’s posse was closing.

El Churo Canyon, about 300 meters long, ran downhill northeast to southwest. At the southern end, it merged with La Tusca Canyon and fed into San Antonio Canyon. The steep ravine, as much as 200 meters deep, was thickly vegetated, particularly along the canyon floor, becoming sparser near the top. In addition to the two sections from A Company at the top of El Churo Canyon, Captain Prado sent his Third Section (Sergeant Huanca) up to the north end of La Tusca. He set up his command post and established a blocking position with his two mortars and single machine gun at the southern confluence of the two canyons.6 By 12:30 pm, Prado’s elements were in position and the search of the canyons began.

Che had split his force into three groups, sending four men (Pombo, Inti, Darío, and Ñato) forward into the upper part of El Churo Canyon and four others to the southerly confluence of the two canyons. The rear guard (Chapaco, Moro, Pablo, and Eustaquio) slipped out before the Rangers got into position. Che stayed hidden in the center of El Churo with the remaining guerrillas. His intent was to block the troops from entering the canyon and escape with his main body by climbing to the high ground. The Ranger forces began searching the canyons, closing in on Che. Immediately there was contact at the north end of El Churo.

Second Lieutenant Perez’ men were taken under fire when they began to cautiously enter the north end of El Churo. Two Rangers were killed in the initial exchange. The movement halted as the Rangers tried to maneuver to take the insurgents under fire. They had cut off movement to the high ground from the north end of El Churo, but could not penetrate down the narrow ravine. Prado called Sergeant Huanca on the radio and told him to rapidly clear La Tusca and get to the canyon confluence. Before the Rangers arrived, Che made his first attempt to break out.

Captain Prado had positioned his crew-served weapons to overwatch the area where El Churo and La Tusca canyons converged. When the guerrillas emerged to begin their breakout, he engaged them with mortar and machine gun fire. The guerrillas retreated back into El Churo with casualties. Che was wounded in the right calf, and his M-1 carbine was destroyed.7 A second breakout attempt resulted in another wounded guerrilla. The tide of battle began to run against the guerrillas.

Prado used his AN/PRC-10 radio to call in his appraisal of the encounter to 8th Division Command Post (CP) at Vallegrande. Two North American AT-6 Texan airplanes carrying napalm bombs and armed with machine guns were launched from Santa Cruz to assist. The narrow, near vertical canyon walls and the close proximity of friendlies precluded using the close air support. An OH-23 helicopter also arrived at Prado’s CP to help with the evacuation of dead and wounded Rangers.8 The restricted maneuver room meant that it would be an infantry slugfest at point blank range.

Sergeant Huanca and his section, having completed their sweep of La Tusca Canyon, were directed into El Churo to drive the guerrillas against the two sections of A Company atop the ravine in a “hammer and anvil” maneuver. Huanca courageously attacked Che’s main body with hand grenades, killing two guerrillas. This forced the insurgents to fall back and enabled the Rangers to get into the canyon. Now Che had no choice but to try to escape, and the only way out was up.

Separated from the rest of his men the wounded Che with “Willy” helping him began climbing out of the canyon. Two Rangers manning an observation post near Prado’s CP caught sight of the two fleeing guerrillas. They held their fire and stayed hidden, allowing the insurgents to climb up the ravine. When they were ten feet away, the two Rangers stood up and took them prisoner. Che had been caught within 15 meters of the command post.9 When asked by Captain Prado to identify himself, he replied, “I am Che Guevara.”10 Prado radioed to the 8th Division CP the news of Che’s capture, then turned his attention back to the battle.

The fighting lasted the rest of the afternoon as the Rangers continued to sweep the canyons for insurgents. Che was detained at Prado’s CP until dusk, and then he and Willy were marched by their captors the two kilometers to the village school at La Higuera. There they were kept along with the bodies of two other dead guerrillas.

Che and Willy were held through the night of 8 October in the schoolhouse at La Higuera. The next morning, on orders from the Bolivian President, they were executed by Bolivian troops.11 In the fighting that lasted until 14 October, the Rangers had nine men killed in action and four wounded. Of Che’s force, eleven were killed, one captured, and five (three Cubans and two Bolivians) escaped into Chile.12

Of Che’s guerrilla band that once numbered more than fifty, only five survived. Che’s dream of starting “one, two, many Vietnams” in the jungles of Bolivia died in El Churo Canyon under the guns of the Rangers. Major Ralph Shelton, commander of the MTT who trained them, summed up Che’s end “Che was trapped by and tried to break through the best platoon in the best company in the Ranger Battalion, Gary Prado’s B Company and the 3rd Platoon commanded by Sergeant Huanca.”13